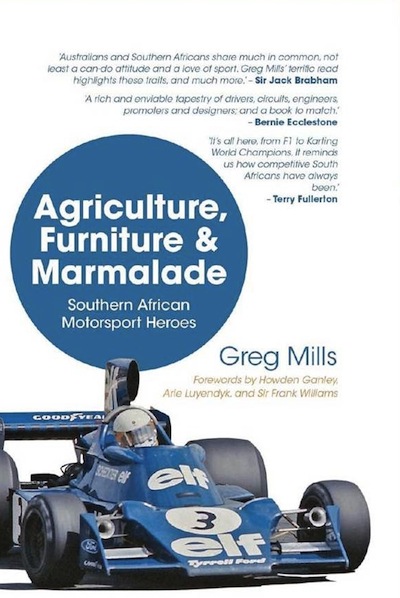

Agriculture, Furniture & Marmalade: Southern African Motorsport Heroes

“Jody Scheckter, to date South Africa’s only Formula One World Champion, received the following advice from Jackie Pretorius on his departure for fame and fortune go England in 1971. ‘Jackie pulled me to one side and told me that I had to learn some big words to impress the Europeans. He said he would give me three then and there—Agriculture, Furniture and Marmalade—preferably to be used in conjunction with one another.’”

Thus begins Greg Mills’ look at the rather fascinating cast of characters who formed the core of motor racing in South Africa over the past half dozen decades or so.

If one reads enough books on motor racing for long enough, there creeps in a certain level of, shall we say, “Been There, Read It,” whether one wishes to admit it or not. Back more than a few years ago, books such as this one seemed to be one of the more prevalent formats for books aimed at Racing Enthusiasts. Some were very good if not outright excellent in some cases, while most, of course, left a bit to be desired.

That said, the title alone and the subject matter piqued my attention long before I laid eyes on Agriculture. I have long had a certain interest in South African motor racing. Your guess as to why is as good as mine, but given that it is a subject that can be considered somewhat off the beaten path, that alone would merit any interest in the topic.

I’m not sure I have read many books—if any—with three Forewords. Here they are from three rather disparate and very interesting people: Howden Ganley, Arie Luyendyk, and Sir Frank Williams. This being somewhat unusual, I took a bit more interest in them than I might otherwise. As it turns out, Ganley (a New Zealander) gave the author the idea for the book, suggesting that Mills write something akin to what Eoin Young wrote about New Zealand’s racing personalities in his 2003 book Classic Racers. I had forgotten that Luyendyk, a Dutchman, had lived in South Africa, his Jaap owning the International Garage on Beach Road, Mouille Point. As for Frank Williams, his first foray as a constructor of sorts, the De Tomaso of 1970, took place in South Africa.

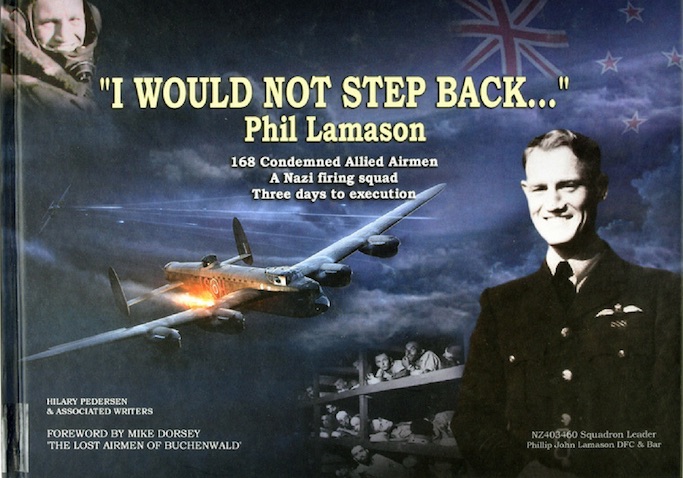

It was interesting that Mills thought to begin Agriculture with Woolf Barnato, heir to the diamond fortune his father, Barney (a prize-fighter and music-hall entertainer born Barnet Isaacs), amassed when he sold out to Cecil Rhodes. Barnato was all of two years old when his father died. After serving in the Great War, Barnato was drawn into motor racing, providing very timely financial backing to the Bentley concern after its victory in the 24-hour race at Le Mans in 1924. As one of the “Bentley Boys,” Barnato only entered three of the 24-hour endurance races at Le Mans; however, he won all three, on the trot no less, from 1928 to 1930. It is Barnato who establishes the linkage that sent many of the South Africans mentioned by Mills to Europe.

Although I had seen the name Bill Jennings on a listing of winners of the South African championship, I will readily admit that I had nary a clue as to who he was. As it turns out, Jennings built the car he used to win the championship, the Jennings-Riley, on three occasions —1954, 1956, 1957. At the time this was scarcely unique, but that Jennings did so while eking along on less than £8 a week certainly was not. As it turns out, it was the Jennings-Riley that Jennings sold at the end of the 1957 season that launched the career of Rhodesian John Love.

John Love and his near win of the 1967 South African Grand Prix is, as it should be, the stuff of legend. That said, I was surprised to realize just how little I actually knew about this six-time South African championship winner. I had forgotten that at one time Love drove for Ken Tyrrell. Likewise, while I knew a bit more about Tony Maggs, I did not realize that it was while avoiding a spinning Maggs at Albi that Love severely injured his left arm, which as Mills suggests more than likely put an end to any real chance Love may have had to be a member of the Grand Prix circus in Europe. Love and Maggs get a very justified deal of attention by Mills, the chapter devoted to them being one that answered more than a few items of my curiosity regarding both the drivers and their era.

My somewhat vague knowledge of Doug Serrurier was previously limited to both his occasional appearance and his LDS cars. Now I have a bit more of an inkling regarding Serrurier and the LDS machines: it is good to know that others seem to be just as confused as I am over just how many of the various LDS machines were made. It also gave me pause, when Mills pointed it out, to realize something that had never before crossed my mind: that, after Jack Brabham, Doug Serrurier was the second driver to drive a machine of his own construction in a world championship event.

One of the distinct pleasures reading Agriculture was not just learning more about those drivers whose names were becoming something more than just names, but those who also served, if you will, as well as getting a better sense for the somewhat exotic world of South African motor racing. While I had seen Alex Blignaut mentioned from time to time in various race reports or other sources regarding South African motor sports, I knew little about him. At least now I have some idea as to the role he played in the sport—the chapter devoted to him seems to be appropriately entitled: “Alex Blignaut, South Africa’s Bernie.”

If you get the sense that I enjoyed this book, you are correct. As I mentioned earlier, a book of this sort is often a Good Idea but often enough falls victim to any number of things, winding up as just another soon to be forgotten book on the shelf. Not in this case. I found myself enjoying it, both as a voyage of discovery for an area of racing that has long interested me, but I did not have much to fill in the gaps. A fascinating and informative book, in other words.

I couldn’t help noticing that there is a photograph of the author conversing with—of all people—Jimmie Johnson, the NASCAR champion. It wasn’t so much who he was speaking to as the location: Charlotte, Virginia. . . . As it turns out, Ken Howe who works for Hendricks Motorsports is South African, which came as a bit of a jolt since I had seen his name many times. I had known that he worked for Al Holbert before moving to Hendricks, but had no idea he was from South Africa. Surprise, surprise!

A small, final comment: Give credit to Greg Mills for enlisting Rob Young in his cause to bring Agriculture, Furniture & Marmalade: Southern African Motorsport Heroes from idea to the printed page. While I am not certain of the true extent of Rob’s contribution to what Mills wrote, I can sat that from what I do know about the history of South African racing, that Rob Young is someone whose knowledge and expertise I truly respect.

Professionally, Mills is an expert in international affairs but if you already know something about South African motorsports you might recognize his name as that of the grandson of pioneer racer and aviator William Arthur Frank “Billy” Mills (1898–1937) who tried his hand in different forms of racing but really became kown for his long-distance, record-breaking trips in the 1920s. And don’t be surprised to see Gregory John Barrington “Greg” Mills, who was a South African karting champion in the 1980s and nowadays regularly competes in local and international historic racing series, at the 2014 Le Mans 24-Hours where for the first time an all-South African entry will compete.

Copyright 2013, Don Capps (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter