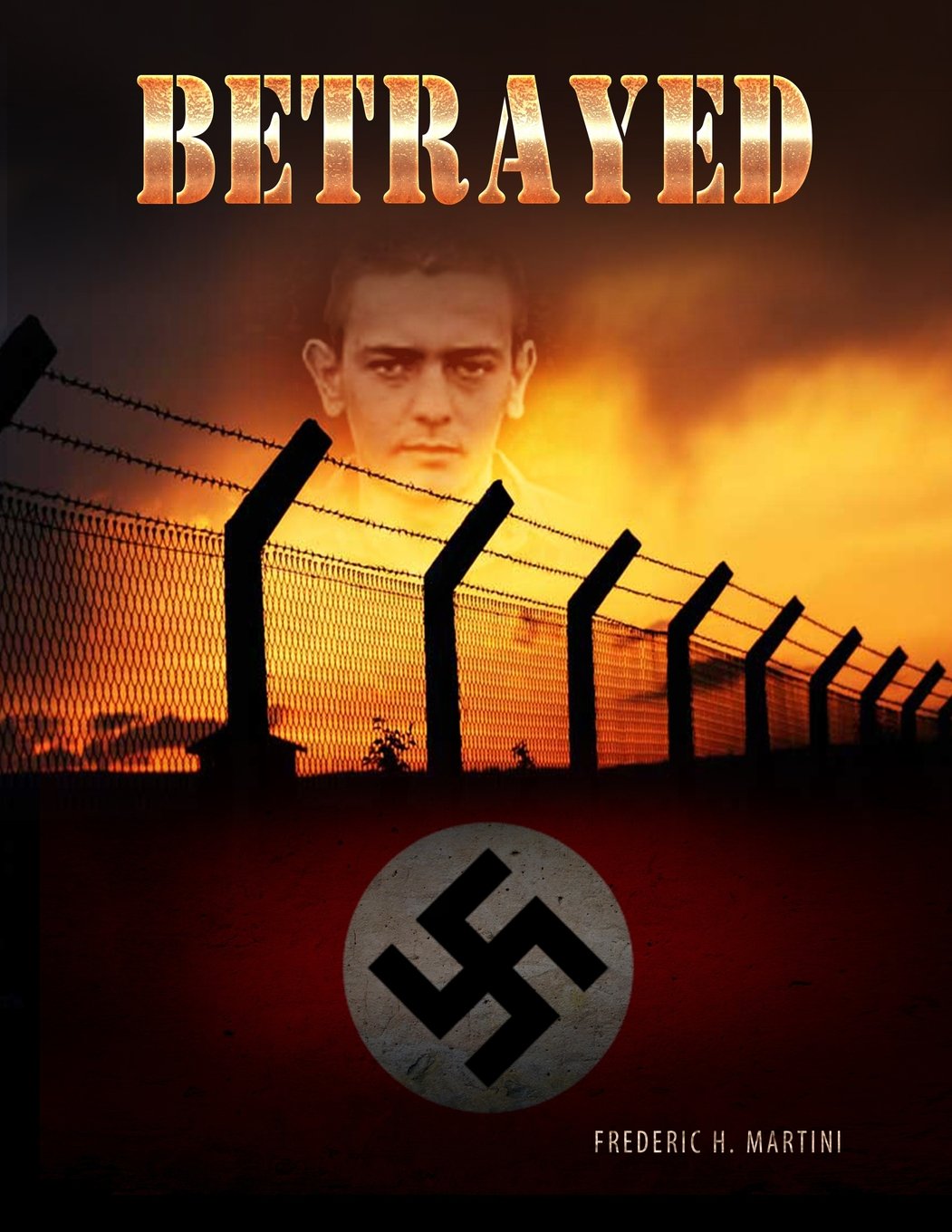

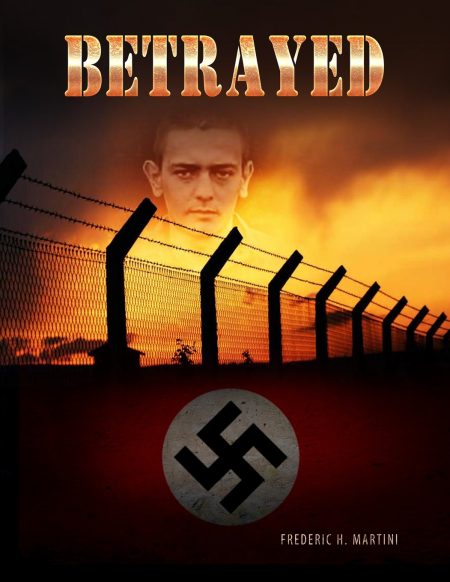

Betrayed: Secrecy, Lies, and Consequences

Of all the dreadful nightmares available to sensitive dreamers of a certain age, the concentration camps run by the German Gestapo must be amongst the worst. This book is an account of how a Staff Sergeant from Brooklyn was incarcerated in Buchenwald; his survival; and his struggle to have his very existence acknowledged by the Veterans’ Administration.

Betrayedhas been written and published by Ric Martini, the son of that airman. During seven years of research he has accumulated about 160,000 scanned pages from American, British, French and German archives, and has ensured that they are widely available, by DropBox, to researchers.

Frederic Cosmo Martini volunteered for service in the United States Army in August 1941, at the age of 23, and transferred to the Army Air Corps after America entered the war. A mechanical aptitude, along with a marksman’s skill and the ability to compensate for relative motion meant that he trained as an air gunner. As an indication of the training required, Staff Sergeant Martini and the other nine members of his B17 Flying Fortress crew did not depart for Britain until 5 April 1944, from Savannah, Georgia, by way of airfields near Richmond, Philadelphia, New York City, New Hampshire, Goose Bay Labrador, Iceland, and Northern Ireland.

Martini goes into great detail of just what it was like to fly as a waist gunner in the B17, with the 9’6″ diameter fuselage restricting movement for the port and starboard gunners and their equipment, closely described, so that they occupied staggered positions; the extreme noise and cold from their open gun ports; the presence of control wires, hydraulic lines and power cables; and the American daylight bombing raids entailing arising at 0230 and returning for a late lunch. If all went well. This crew had flown five training missions, completed seven combat missions, but had two crash landings, one in the English Channel.

On this day, 12 June 1944, B17 serial number 43-97818 was part of a bombing raid to try to prepare the ground for the Allied landing soldiers, who remained bogged down near the Normandy coast. Heavy anti-aircraft fire knocked out an engine, and the resulting fire quickly disabled the aircraft, so the pilot, Lieutenant Loren Jackson, gave the order to bail out! Martini was badly wounded by shrapnel, and sustained further damage to his left leg in the parachute landing.

Found by French farmers who happened to be active members of the Resistance, Martini was hidden successfully for some weeks, along with another American and a British airman, until they were betrayed by a French double-agent, and taken to Gestapo Headquarters in Paris.

An increasingly paranoid Adolf Hitler had, by June 1944, become dependent upon the SS under Heinrich Himmler, with the German army and air force considered unreliable, particularly since the July plot to assassinate Hitler. On 17 June a decree was issued that uniformed personnel parachuting into France were to be executed, and on 22 July, this was extended to any captured out of uniform, who were to be executed as commandos.

After a spell in Fresnes Prison, which included beatings and interrogation, Martini was among over 2,000 prisoners to be loaded into grossly overcrowded cattle wagons. He took particular note of an airman who stood up to an SS officer, demanding that he and his colleagues were military prisoners, not cattle, and should be treated under the provisions of the Geneva Convention. This was a New Zealander, Squadron Leader Phil Lamason, who assumed command of the airmen, insisting upon their maintaining military discipline, including saluting and marching. Lamason’s story has been told in his autobiography I Would Not Step Back. This detail, including names, reported by Martini Sr, and recorded by his son, is quite astounding.

One prisoner, Canadian Flying Officer Joel Stevenson, escaped en route, but after about five days on the train, 168 Allied airmen arrived at Buchenwald concentration camp, near Weimar. They consisted of 82 Americans, 9 Australians, 48 British, 26 Canadians, 1 Jamaican, and two New Zealanders. They joined approximately 82,000 other inmates, including about 35,000 working in other labor camps.

Martini’s account of the 61 days spent in Buchenwald, most of them without shoes, is appalling, but it needs to be read. Autumn was well advanced by the time a visit to Buchenwald by a Luftwaffe officer, and an appeal to him by a German-speaking American airman, started an investigation into their status. Theirs was a “Not to be transferred” status, and it was possible, or even probable, that the airmen would be executed before the Luftwaffe could intervene. However, in two batches, in October and November 1944, the surviving airmen (two died in Buchenwald) were shipped, again in railroad wagons, to Stalag Luft III in Poland. This was the camp from which “The Great Escape” had been made in March, and the relationship between the prisoners of war and the guards was very poor, as a result of executions of captured airmen on Hitler’s orders. Despite skepticism that the Buchenwald Airmen could have suffered so, interviews with the senior American POWs were recorded, and Squadron Leader Lamason made a report to a visiting Swiss delegation in early November.

As Russian troops advanced into Poland, Stalag Luft III was evacuated in late January 1945. That was a particularly brutal winter, and Martini’s description of the forced march and rail journey to another prisoner of war camp near Berlin is very sobering indeed. By this stage of the war food was very scarce in Germany, and the prisoners’ position was way down the food chain. Red Cross parcels were getting through, but for Martini and his non-commissioned officer colleagues, not protected from having to work by the Geneva Convention, as were those holding commissions, the weight loss of about 1 pound a day in Buchenwald was not much reduced, and they were in extreme bad health by this time.

Repatriation took a long time, and interviews with the War Crimes team took place. Martini took advantage of some spare time in Paris to search for those who had helped him, and also for those who had betrayed him; he had been streetwise even before enlisting in the Army, and was carrying a gun, in case he needed it.

Martini’s story is a fascinating adventure story, but a true and tragic one. His son has told it well, and has related a parallel story in alternate chapters, about a German nobleman, SS officer, and rocket scientist—one Wernher von Braun. During efforts to bring the designs of V1 and V2 rockets to production, slave labor from the concentration camps was used, to von Braun’s and his colleagues’ certain knowledge, but the American interest in rocket technology meant that von Braun was protected from investigation at a very high level, despite the FBI’s interest in him.

By contrast, Martini’s injuries prevented his maintaining appropriate employment, and he was rated at a 50% disability, receiving a pension that had to be reviewed annually. Because a congressional report stated that no POWs had been held in concentration camps, Martini’s claims were considered as having a psychological basis, and his claims often resulted in his pension actually being reduced.

This book is strong stuff, and as an account of extraordinary experiences happening to an ordinary man it makes compelling reading. He married, had a son who now divides his time between Honolulu and New Zealand, and after a series of jobs where he had difficulties because of his ruined feet, eventually had a fulfilling career in an electronic company which, ironically, had a manufacturing role in Apollo capsules, and Fred Martini was introduced to Dr. Wernher von Braun. Martini’s health was poor, but he survived until September 1995. His story needed to be told, and it needs to be read.

Copyright 2018, Tom King (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter