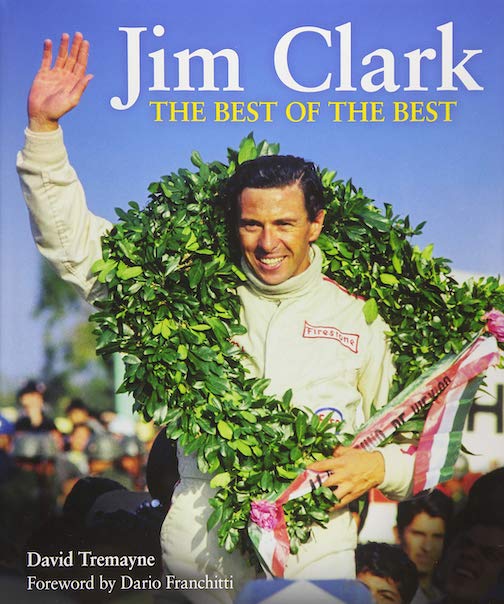

Jim Clark – The Best of the Best

Motoring and motorsport are no strangers to commemoration. Since we discovered nostalgia, some time back in the 1990s, not a year has passed without yet another “celebration” of a past Grand Prix or Le Mans victory, or the debut of a sports car. You can take it as read that the word “icon” will be strewn around the publicity hype and it doesn’t take too much cynicism to believe that the motivation behind most anniversary celebrations is more commercial than commemorative. But it wasn’t like that on a cold and grey morning in Duns, in the Scottish Border country, on April 7, 2018. Hundreds of us had assembled to mark the fiftieth anniversary of Jim Clark’s death at Hockenheim and the pervasive mood was one of quiet and deeply felt respect. I was aware then that David Tremayne had been writing a book on Jim Clark, intended to be the definitive effort, and my expectations were high because one of his previous books, The Lost Generation, had moved me to tears. First Roger Williamson, then Tony Brise and Tom Pryce had died between 1973 and 1977, leaving the hopes of a British resurgence in Formula 1 on the shoulders of James Hunt and John Watson. Nobody could have told the story of the lost drivers better.

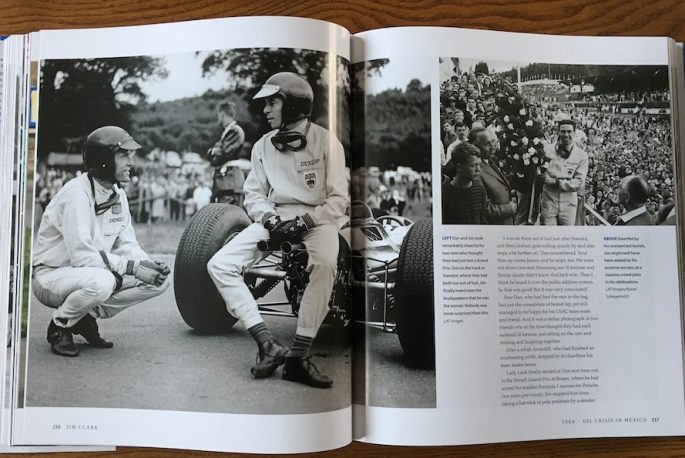

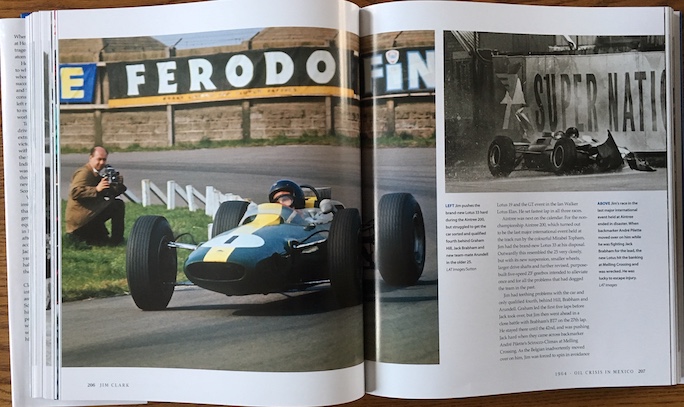

The loss of Jim Clark created a void that, in the hearts of so many, has never and could never be filled. There’s no shortage of books written about Clark but it is to Tremayne’s great credit that nobody need ever write another one because this book is definitive. It is a huge work, 520 pages long and superbly illustrated with hundreds of black/white and color photos. Some, such as the picture of Clark and Dan Gurney exchanging smiles at Spa’s Stavelot corner in 1964, are familiar but I suspect many others have never been seen by the public before.

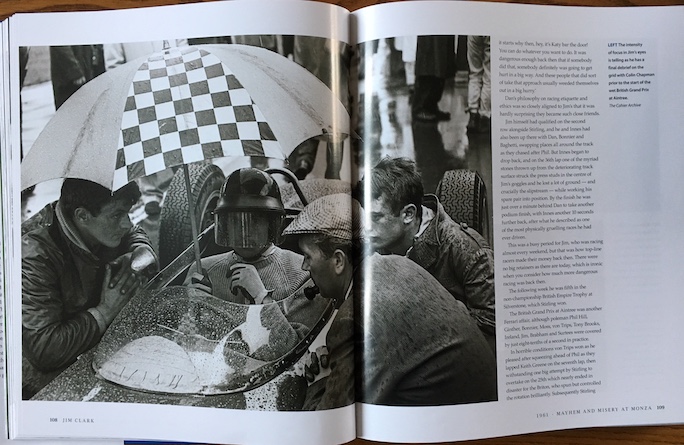

As ever with pictures of a past era, it is the unwitting testimony they bear that fascinates as much as the notional subject matter. It is easy to forget the contrast between the easy-going informality of the typical race paddock back then and the buttoned down formality of the clothing, with hats and ties much in evidence and skirts and scarves almost de rigueur for the ladies. Apart, that is, from the startling exception of the splendidly jump-suited Linda Vaughn, “the first lady of US motorsport.” The book measures 10 x 11 x 1.5 inches and its hefty 6 pounds weight is an ironic counterpoint to Lotus boss Colin Chapman’s famous mantra, “Simplify, then add lightness.”

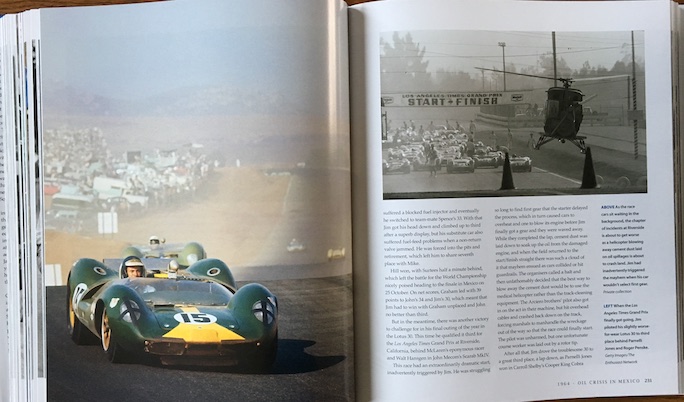

The author devotes 16 of the book’s 21 chapters to a comprehensive account of Clark’s career, often on a race by race basis. It’s an exhaustive approach and, to the reader who devours this book as eagerly as I did, it can be an exhausting one too. But what a story it tells, from Clark’s early days competing in such unlikely machinery as Ian Scott-Watson’s DKW Sonderklasse to racing the brutal V8-powered Lotus 38 in front of the huge Indianapolis 500 crowd. On reading the book, it’s difficult not to deprecate the modern Grand Prix driver’s relatively relaxed schedule of races compared to the frenetic succession of events his 1960s counterpart had to endure. In 1965, Clark’s first race took place at South Africa’s East London circuit on January 1 and ended, over sixty races later, on October 31 at the Los Angeles Times Grand Prix at Riverside. The events Clark contested weren’t all “big ticket” ones either, and Tremayne’s revelation that Clark had competed in the St. Ursanne-Les Rangiers hill climb in 1965 was a delight, especially as it had been at the wheel of the Lotus 38 . . .

Jim Clark’s career arc spanned the last years of the era of front-engined sports cars such as the D-Type Jaguar via mid-engined brutes like the Lotus 40 sports racer to the exquisite Lotus 25 and 49 Formula 1 cars. The latter two redefined the Grand Prix car and their legacy can still be seen today. Tremayne recounts how Clark relished driving anything and everything and was able to adapt his style almost instantly to whatever demands a car made of him. This was never better illustrated than by Clark’s few laps at Rouen in the prewar ERA R5B “Remus” owned by the Hon. Patrick Lindsay. The car’s owner, no mean racer himself, had put the car on pole for the 1964 French Grand Prix support race and Clark, on pole too for the main event, was invited to try the old racing car. That he was quicker than Lindsay might not have been a surprise, but by four seconds and within only a couple of laps?

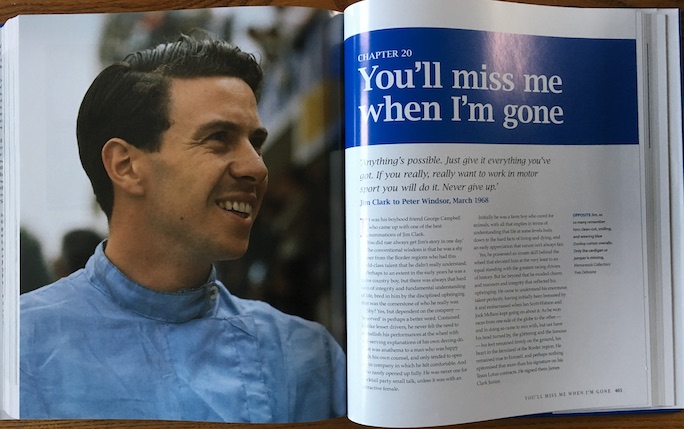

Clark was not the only Grand Prix driver who was capable of almost superhuman feats at the wheel of course, and one only needs a superficial grasp of the history of the sport to be aware of the brilliance of drivers such as Fangio, Moss, Senna, or Schumacher. But what most distinguishes Clark from nearly all of his peers was the essential decency that came to define the man. As Tremayne puts it, “his fundamental humility never left him.” He describes how, when beaten to the championship by Graham Hill in 1962, Clark said “I think Graham made a better champion than I’d have done.” With the possible exception of the self-analytical Damon Hill, can you imagine any Formula 1 driver of the last half century saying words to similar effect? Even hard as nails Indy drivers such as Parnelli Jones and A.J. Foyt, whose Brickyard hegemony was so disrupted by the little rear-engined Lotuses driven by Clark, adored him. Tough Texan Foyt commented “I liked him, and I wasn’t real fond of the Brits . . . he was kinda quiet, not a smart ass or a jerk. He wasn’t a prima donna.”

Tremayne’s analysis of Jim Clark’s relationship with his friend, mentor, and team boss Colin Chapman is insightful, especially as it contradicts the conventional narrative that their relationship was always harmonious. I was shocked to read of Chapman’s brutal humiliation of Clark in front of the team at Indy in 1966, when the driver was failing to match the pace set by team mate Al Unser: “All of these boys are giving their best, what about you James?” But, as the author observes, “Chapman didn’t always observe niceties when the chips were down.” Incidentally, it is gratifying that the book is far from Eurocentric, a failing of some racing literature, which can treat Can Am, Indy or NASCAR almost parenthetically, as if they were the uncouth “below stairs” poor relations of pur sang Grand Prix racing.

Tremayne clearly spent a huge amount of time not only researching the minutiae of Clark’s racing career, but also exploring the relationships he enjoyed with family, friends, and lovers. From the picture he paints, you just know you’d relish an afternoon spent with those hard-working, decent and honest people of the Border country—men such as his early mentor Ian Scott-Watson, Jock McBain and my own distant relative, Jimmy Somervail, whose tales of the Border Reivers used to so entrance me. Clark never married but certainly did not lack for female company and Tremayne includes warm recollections from many girlfriends, most notably Sally Swart (nee Stokes) and Elizabeth “Widdy” Padfield, who reminisced “he was the love of my 20s, and part of my life.”

Remarks like this inevitably trigger “what might have been” speculation in the reader, and this reviewer is no exception. I never saw Jim Clark race from trackside, and only once did I see him race live on television, at the 1967 Italian Grand Prix. It was the first Grand Prix I had ever watched and I remember sitting in front of the TV, curtains drawn against the September sun, and being entranced as Clark tigered his Lotus 49 back to the front after a pit stop to replace a punctured tire. Not for the first time, his Lotus spluttered out of fuel almost within sight of the flag, this time leaving tough guys Jack Brabham and John Surtees to duke it out at Parabolica. It may have been a day of days for Surtees in the Honda but the drive by Clark is why I still rarely, if ever, miss a Grand Prix. And it is also why I can never forget being in the family Humber Hawk on April 7, 1968, as we returned from holiday in Northern Ireland. The news played from the crackly car radio (probably still called “the wireless” in those analog days) and, in the sepulchral tones that BBC announcers reserve for bad news, I heard the words “The racing driver Jim Clark . . .” and immediately I knew the rest. Clark lit the flame of my own passion for the sport and whilst it may still burn bright, it could never again burn as brightly as it had done so on that long ago day at Monza.

I don’t usually indulge in “what ifs?” when it comes to racing drivers, as that way madness lies. However I will confess that, before I even opened this book, I did wonder what Jim Clark might have achieved if hadn’t decided to race in the Formula 2 race at Hockenheim instead of his original plan to race the Ford F3L at the BOAC 500 at Brands Hatch. If he had stayed with Lotus (which must be safe to assume?) I think world championships in 1968, 1970, and 1972 would have been almost guaranteed and, if 1978 had been his swansong, there’d have been another title, his sixth, in the “something for nothing” Lotus 79. After all, Clark was only four years older than Mario Andretti, who did win the title for Lotus that year. The author speculates on similar lines, but points to the evidence that Clark might have retired at 35, in 1971. Either way, in a parallel universe, I cannot help but wonder if that engaging smile might still be lighting up conversations at Edington Mains farm in Berwickshire.

Jim Clark has finally got the book he deserves and I recommend it without reservation. It is a masterful piece of work, of which David Tremayne should be deeply proud. And I know that, just like him, thoughts of Jim Clark will mark every mile of my next pilgrimage to his Memorial Room at 44 Newtown Street, Duns.

Postscript: if you do get this book, don’t miss the poem on the flyleaf that was written by the author as a teenager in 1968. The words, and the emotions behind them, speak volumes.

Shortlisted for the 2018 RAC Specialist Motoring Book of the Year.

Copyright 2019, John Aston (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter

I just read John Aston’s review of our Jim Clark book and I’m sitting here home alone with my eyes stinging—thank you all at Speedreaders. Not just for getting it all in the first place and being racers. But for giving a book such a decent amount of space and, of course, for the kindness of your words. When you are your own harshest critic, it’s nice now and then to receive, and let yourself accept without trying to pick apart, praise from others.

Most of all I’m happy that I did the right thing by Jim. You know in your heart whether you’ve done that, of course, but it’s an even better feeling when others say it. Please pass on my thanks to John for his words, and all good fortune with your enterprise as you move ahead. You guys sound like a good bunch to hang out with!

Best regards, David Tremayne