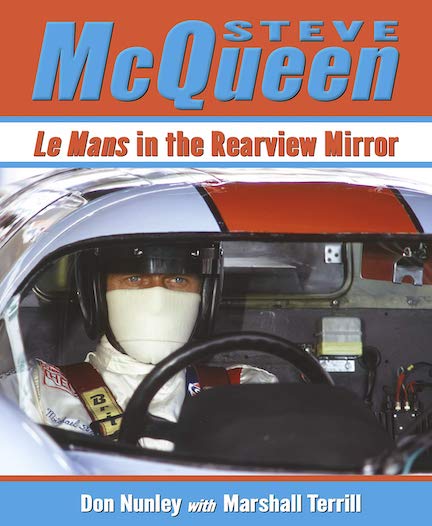

Steve McQueen: Le Mans in the Rearview Mirror

“Most people have no difficulty discerning the difference between real life and reel life, but Steve McQueen did during the making of Le Mans.”

This sentence is the key to understanding what all went wrong on the set of the 1970 movie that had been “marinating in [Steve’s] head for already ten years,” so wrong that author and Le Mans prop master Nunley calls it a “nightmare of epic proportions” that everyone was eager to erase from their memories and has taken him years to come to terms with.

Mind you, Nunley (b. 1939) was no rookie to movie-making, had learned the craft at his prop master father’s feet and, having just come off the highly acclaimed—and most expensive—movie at the time, Little Big Man (1969), counted as “one of the top men in [his] field.”

Any number of things he writes about give one pause: that the movie was slated to be shot in 6 weeks (it took over 5 months—not a terribly long time, except when everyone wishes they were somewhere else), that first then-rookies Steven Spielberg and then George Lucas were considered as directors before John Sturges got the gig (only to quit in frustration part-way through over McQueen’s lack of respect—never mind that their previous collaborations had been “responsible for breaking McQueen into the big time”), how McQueen’s journey from struggling actor to movie mega star fueled his sense of entitlement and also paranoia, and just how much this one particular movie became his identity. “I’m not sure whether I’m an actor who races of a racer who acts.”

Any number of things he writes about give one pause: that the movie was slated to be shot in 6 weeks (it took over 5 months—not a terribly long time, except when everyone wishes they were somewhere else), that first then-rookies Steven Spielberg and then George Lucas were considered as directors before John Sturges got the gig (only to quit in frustration part-way through over McQueen’s lack of respect—never mind that their previous collaborations had been “responsible for breaking McQueen into the big time”), how McQueen’s journey from struggling actor to movie mega star fueled his sense of entitlement and also paranoia, and just how much this one particular movie became his identity. “I’m not sure whether I’m an actor who races of a racer who acts.”

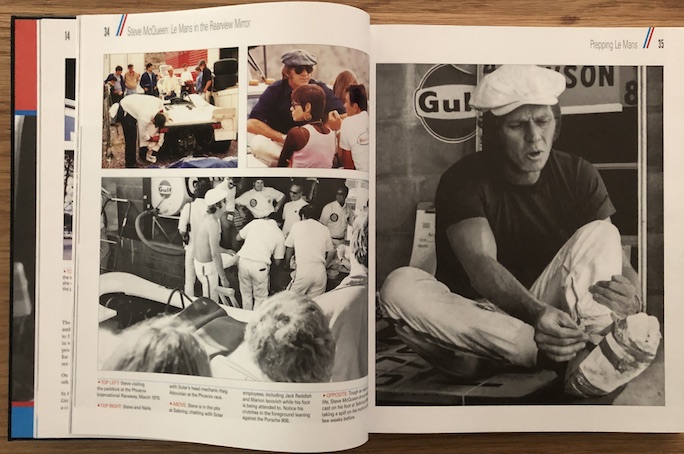

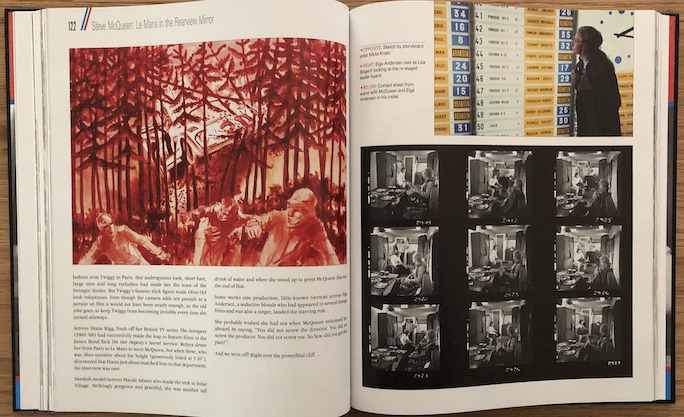

After first explaining his own professional journey and the role of the prop master, Nunley builds up to why this movie mattered so much to McQueen by juxtaposing it to that other great racing movie of the time, the James Garner vehicle Grand Prix whose release in 1966 had beaten the McQueen project Day of the Champion to the box office and, to add insult to injury, gotten funding for Day cancelled. Much is made of Le Mans being so light on story line (unlike Denne Petitclerc’s original novel and screenplay) so Nunley makes a point of saying that McQueen saw it as a pseudo documentary, more in the vein of his earlier motorcycle doc On Any Sunday rather than his most recent full-blown Hollywood movie, Bullitt. That movie, incidentally, had featured pretty hair-raising driving scenes but McQueen felt he had to prove his racing chops and therefore campaigned a Porsche 908/2 in several SCCA events in preparation for his movie starting only a few months later. At the biggest race of that season, the 12 Hours of Sebring, he and co-driver Peter Revson, a ranked F1 driver, missed 1st place by a mere 28.8 secs—and McQueen had one foot in a cast thanks to a motorcycle accident a few weeks prior!

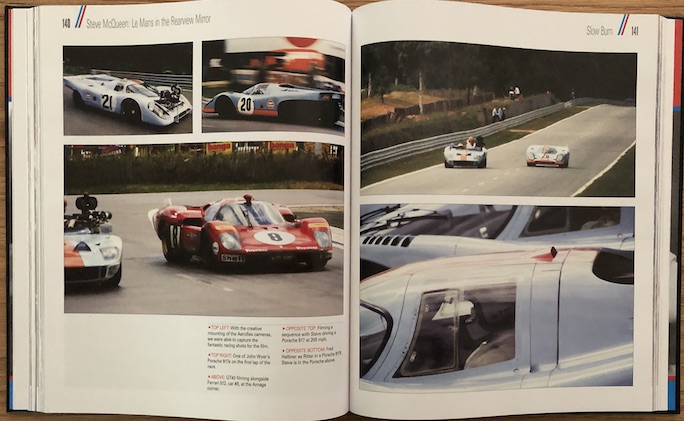

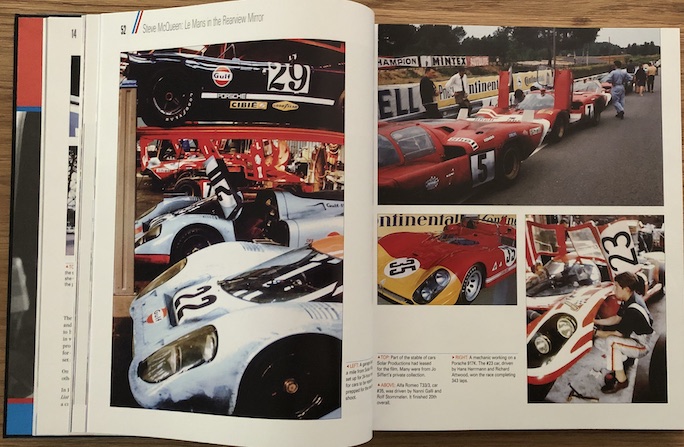

That very 908 was the car he intended to race in Le Mans, which he would be forbidden to do. His resultant anger had far-reaching consequences for the movie budget/schedule and morale right from day one. This is probably a good time to point out that the movie was shot real-time during a regular race, the 38th running of Le Mans, with movie cars thrown into the action, and then fleshed out with the bits that make it a movie-movie. (And here’s a howler: the 908 camera car ran so well that it climbed to 2nd in its class and 5th overall, so McQueen seriously wanted to relieve it from camera duty and just let it go for the race win! Only 16 of the original 55 starters were still running so the field was pretty thin by then.)

All of the above should be giving you the impression that there are a lot of moving parts to this movie and therefore to Nunley’s story—and we’re barely a third into the book! As prop master he was as he says “the first to arrive on set and the last to leave” and as one of the earliest hires and a key man on the advance team to France he really is in an utterly unique position to know first-hand things others do not.

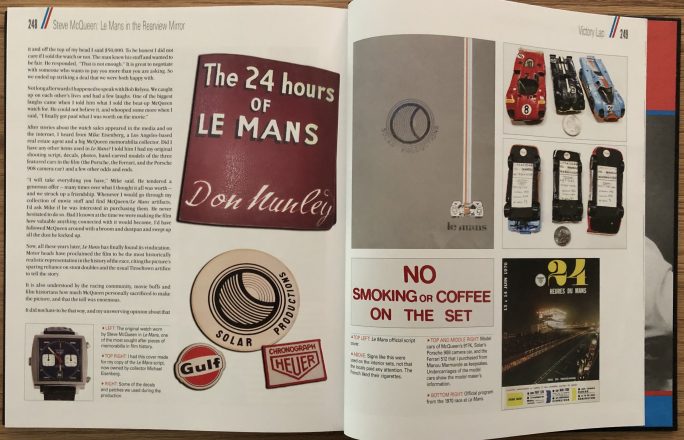

Racing obviously involves cars, and Nunley tells and shows a lot of the movie cars. That not all questions really curious folk will have are answered may be because they didn’t fall into the prop master’s purview. But there is one other item that totally did but which is not exhausted fully and that is the story of the famous square-dial Heuer Monaco chronograph wristwatch. It would in later years assume cult status, with one of the movie watches selling for over $800K in 2012. Even less is said about the other brands Nunley presented to McQueen for selection (who wore a Rolex as a personal watch and for the movie favored Omega—until Nunley pointed out that the patch on his driving suit, inspired by Jo Siffert’s livery, said “Heuer”) or any of the other Heuer timing gear. Nunley, presumably at the end of the shoot, privately bought all the pieces from Heuer (who had declared them as gifts to get them through customs) at a low bulk price, including 3 of the 6 Monacos (other books imply a quantity large enough that McQueen could give them away to cast and crew). Much more about these items than what is recorded here is publicly known, and the reason to dwell on this is that we remain unenlightened as to why Nunley sold two of his on eBay for a mere $9,000 each!

Aside from Nunley’s insider position there is another thing that sets this book apart: he is not a sycophant. He is as acutely critical of McQueen’s ego and excesses and philandering (“he had the instincts of a coonhound”) as he is full of praise for his acting chops and method. Which brings us to the other name on the cover, Marshall Terrill. A veteran film, sports and music writer he has one the better bios of the subject to his name, Steve McQueen–The Life and Legend of a Hollywood Icon, which may itself become a feature film. He was also the executive producer on a 2017 documentary about McQueen. It is reasonable to postulate that the macro vision this work affords him complements Nunley’s Le Mans-specific insights.

There is no reason to doubt the veracity of the Nunley account, the book is eminently readable and engaging, and it brings many new tidbits to light. It is also most excellently illustrated. Some of the photos you will have seen elsewhere—but that’s just because they are good.

Copyright 2019, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter