Inside the Machine: An Engineer’s Tale of the Modern Automotive Industry

by David Twohig

by David Twohig

“Nissan’s ‘Five Whys’ involved simply asking the question ‘Why did that happen?’ five times. Very basic, very obvious . . . and amazingly powerful.”

There is a shameful tendency in the car enthusiast community to sneer at those machines that sell in the greatest numbers—cars like the Ford Fiesta, Honda Jazz (aka Fit in the USA) and Toyota Corolla. “White goods,” “dynamically flawed,” “mundane styling” we sneer, before dismissing such vehicles with that most patronizing insult of all—“transport for the masses.” But hold on, wasn’t the fact that the Ford Model T enabled millions of Americans to travel further than a horse ride from home one of the greatest acts of liberation the country had ever known? The brilliance of the light cast by automotive tours de force like the Cord 810, the Lamborghini Miura, or the McLaren F1 has been blinding the vision of generations of car enthusiasts. So myopic has the archetypal car guy become that he or she affects to forget that ordinary folk don’t want to buy complicated, expensive cars that do things they don’t need or even want. Reading this outstanding book by David Twohig, the gifted automotive engineer, I gained a profound understanding of the staggeringly complex process and massive financial risk involved in designing the modern mass market automobile. I will never look at an early Nissan Qashqai in the same way again, the rear fog light especially . . .

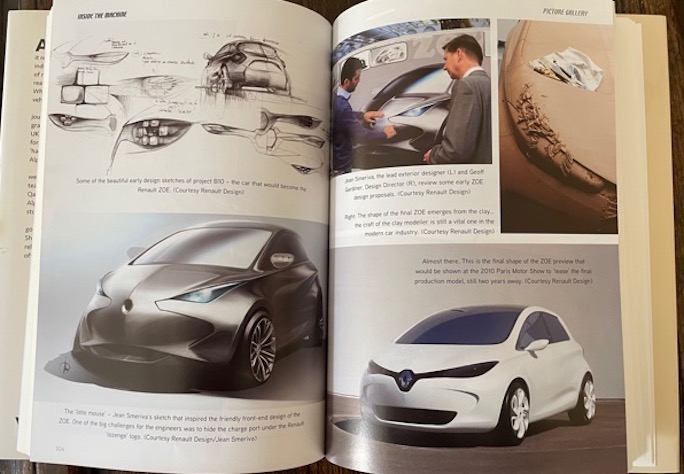

This is a compact, 192-page, 15-chapter hardback but, in their trademark style, Veloce have managed to fill this pint-sized book (8 x 6 inches) with a generous quart of material. The book’s 85,000 words appear in relatively small font but retain legibility thanks to the Seravek (Regular) font. There is a small selection of photographs that feature the three machines whose creation this book describes, the Nissan Qashqai SUV, the Renault ZOE EV [1], and the Alpine A110 sports car. The illustrations are unremarkable but the text more than makes up, as this very well written book reads almost like a thriller at times, especially in the story of the challenges Twohig faced with the Alpine A110.

Twohig is an Irish engineer who spent most of his career working for the Renault/Nissan alliance, reporting to some of the biggest beasts in the automotive jungle, including Carlos Ghosn and Carlos Tavares. The insight which the author brings to the different working cultures of Japanese and French firms is fascinating. One senses that it was the former that had the most profound influence upon him, but as a Francophile Brit it was hard for me to decide which was the more absorbing. It was—by a nose—the Nissan experience because not only does Japanese business culture intrigue, it was that very culture which helped to save what little was left of the British car industry in the late 20th century. Nissan had established a manufacturing facility in the economically deprived North East of England and I enjoyed reading how the inclusive Nissan culture of Kaizen (continuous improvement) and Douki Seisan (simultaneous ordering) transformed an industry that had been almost destroyed by industrial unrest, crazy hierarchies, and archaic working practices.

Twohig writes about both the technical and human aspects of his career and, although both Qashqai and ZOE projects were huge professional challenges, it is clear that the Alpine A110 project was the most fulfilling of his career. Originally, this was to be a joint venture with British sports car maker Caterham, but “what had somehow been missed during the due diligence checks . . . was that Caterham had no actual cash.” The A110 had a difficult conception, as there were signs from the very beginning that Renault (and Carlos Ghosn in particular) was not irrevocably wedded to the project and, after weathering the many financial and engineering storms that beset the car during its hurried gestation, even worse was to come. While being road tested by BBC Top Gear presenters Chris Harris and Eddie Jordan—neither shy or retiring types—the Alpine very publicly burst into flames and was completely destroyed. That could have been the end for both the car and its engineer as, faced with a near impossible deadline, Twohig and his team had first to analyze the molten pile of metal to find out what had happened, and then decide what had to be done to fix it. The account of this forensic exercise is riveting , and rarely has the expression “snatching victory from the jaws of defeat” been more apt. The fact that the A110 was subsequently subject to universal adulation by the motoring press is testament not only to the car’s inherent qualities, but the skill and determination of David Twohig.

What surprised me most about this book was how much I enjoyed reading about the minutiae of car design, from the rigorous cost control, the hothouse of internal politics, the need to balance market appeal with technical innovation, and the onerous, demanding impact of safety and technical regulation. I have been devouring car magazines for decades, but I confess that I have often glossed over the “industry news” sections and I often only skim road tests of the sort of cars most of us actually buy. It’s tempting to ignore the meat and potatoes of the automotive scene when there’s the amuse bouche of Formula One to enjoy, or the sports car soufflé of a Lamborghini or Ferrari road test to tease our taste buds, but this book brought me up short. I was reminded how the cars most of us lust after are essentially mere frivolities, and almost devoid of nutritional value. Compared to the challenge of creating a family car designed to be sold by the million, at tiny profit margins and in a hyper competitive market, the creation of absurdly complex, hugely expensive supercars for an exclusive market seems almost straightforward. Think about it—an entire Renault ZOE costs about the same as specifying “Matt Aluminium Opaco” paint on your $220,000 Ferrari Roma . . .

Twohig writes with easy confidence and an accomplished style that complements his engineering skill. I enjoyed his waspish dismissal of cars such as the New Beetle and MINI, which had “. . . ended up as cheesy neo-retro replicas, clumsily reproducing chrome and toggle switches and cynically playing with customers’ emotions.” Ouch. In contrast, he describes the A110 as having “a dab of the original’s perfume behind the ears, not spraying it all over the place.” That such entertaining personal opinion is complemented by deep insight into the bewilderingly complex world of automotive manufacture that we take for granted makes for a deeply rewarding read. This book deserves a place in every car enthusiast’s library and is in my personal shortlist of automotive book of the year. It really is that good.

- [1] ZOE – so why the capitals? Because the real-life Mesdames Zoé Renault threatened legal class action because of the trauma of sharing their name with an electric family hatchback. We should be thankful that Mercédès, Jellinek, and Elisa Artioli did not have such scruples!

Copyright 2022, John Aston Speedreaders.info

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter