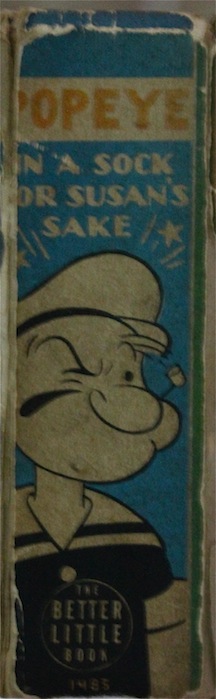

Popeye In a Sock for Susan’s Sake

aka Popeye and a Sock for Susan’s Sake

Looking a bit taller, a smoother chin, a longer nose, crudely drawn, he made his debut on January 17, 1929. When Ham Gravy and Castor Oyl, Olive’s brother, needed an experienced sailor to command their recently acquired ship, they approached the man: “Hey there! Are you a sailor?”

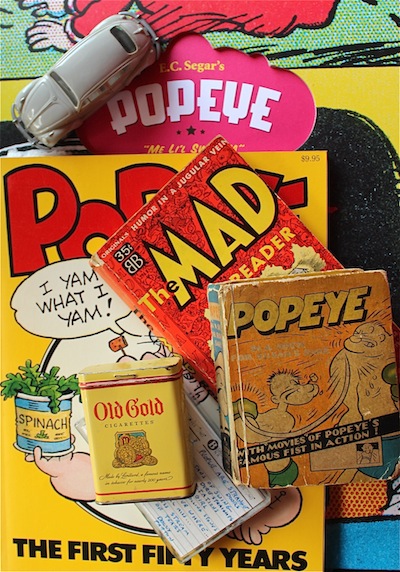

Popeye’s first words ever: “ ‘Ya’ think I’m a cowboy?” And not long after, Popeye becomes the undisputed star of Elzie Segar’s cartoon strip, Thimble Theatre, and by stealing Olive away from Ham, begins a love story that would last decades. Throughout his career as a star of both a Sunday and a daily comic strip (later drawn for years by Bud Sagendorf); an indefatigable actor in the beloved, extremely artistic and clever Fleischer cartoon series (1933 through 1942)—also starring in at least three other cartoon series (becoming less artistic and clever as time went on); the title character in a half-century of comic books; a face and a name for toys, games, puzzles and foodstuffs (notably spinach); and during the 1930s, one of the many stars found in Whitman’s Big Little Books and Better Little Books. When I was a kid back in Pittsburgh, we had a handful of Little Books around the house: I recall reading repeatedly Dick Tracy, Mickey Mouse, Little Orphan Annie, and The Phantom. I came by A Sock for Susan’s Sake as an adult.

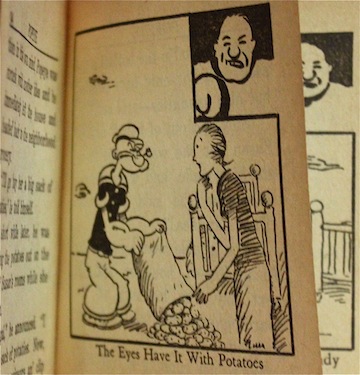

Sock is a depression-era story. Susan Brown, poor but proud, honest but stealing fruit to eat, is being arrested as our hero comes upon the scene. The kindhearted cop on the beat would rather not make the arrest, but mean, ugly Whiskers, the fruit vendor, insists that justice be done. Susan is jailed, but Popeye busts her out. He wants to help, but Susan, maintaining her dignity and her honor, refuses, even when Popeye dresses as an old woman to give her much-needed food and clothing, among them “pananties and a brazoo.” Susan quickly sees through the disguise, and as a respectable maiden “took the potaties but not the pananties.” Susan gets arrested once again; Popeye engineers a second jailbreak, and despite her protests, the pair go out tramping to live on the road. With Popeye socking this one then that one “for Susan’s sake;” getting arrested again, this time by a small-town constable whose kindhearted wife makes sure the jailed Susan and Popeye are well fed and comfortable; being arraigned and put on trial with a sympathetic judge presiding; getting acquitted; and finally taking on the prizefighter King Smacko to earn money, the adventure eventually plays itself out. The story abruptly ends with a jealous, dangerous Olive Oyl on Popeye’s trail.

Sock is a depression-era story. Susan Brown, poor but proud, honest but stealing fruit to eat, is being arrested as our hero comes upon the scene. The kindhearted cop on the beat would rather not make the arrest, but mean, ugly Whiskers, the fruit vendor, insists that justice be done. Susan is jailed, but Popeye busts her out. He wants to help, but Susan, maintaining her dignity and her honor, refuses, even when Popeye dresses as an old woman to give her much-needed food and clothing, among them “pananties and a brazoo.” Susan quickly sees through the disguise, and as a respectable maiden “took the potaties but not the pananties.” Susan gets arrested once again; Popeye engineers a second jailbreak, and despite her protests, the pair go out tramping to live on the road. With Popeye socking this one then that one “for Susan’s sake;” getting arrested again, this time by a small-town constable whose kindhearted wife makes sure the jailed Susan and Popeye are well fed and comfortable; being arraigned and put on trial with a sympathetic judge presiding; getting acquitted; and finally taking on the prizefighter King Smacko to earn money, the adventure eventually plays itself out. The story abruptly ends with a jealous, dangerous Olive Oyl on Popeye’s trail.

What is striking here is that for a book presumably geared primarily towards children (more on that later), it exhibits a remarkably strong vocabulary. Adverbs are used in abundance: “brusquely,” “determinedly,” “disconsolately,” “incredulously,” “haughtily.” “Confidential,” “dumbfounded,” “patronage,” “tirade,” “turmoil” or “wan” would not be readily found in children’s literature today. We find Popeye, before meeting Susan, in “happy reverie” and a policeman “trudging away, shaking his head in deepest perplexity.” Neither the mention of a lady’s unmentionables (pananties and a brazoo) nor a suggestion that a lady “peel off and take a bath” are generally found in books for the younger set. When Susan is accused of taking her bath “in our drinking water,” an indignant juror worries aloud that “I’ve been using it for chasers.” Sentence structure seems bold if in fact this book had been conceived for children; compound and complex sentences (including at least one compound-complex sentence) are peppered throughout—as is the use of the dash.

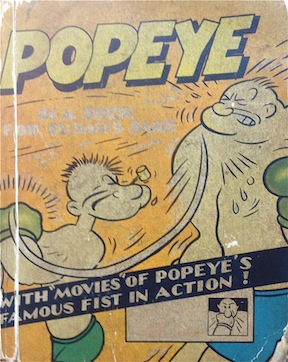

On the other hand, the format of Sock, the format of all of the Big Little Books and Better Little Books, would be an odd one for mature readers. On the left, with roughly seventy-five words per page, with an extensive use of dialogue, the story unfolds; on the right, with only a small border, the page is taken up completely with a captioned cartoon. And as an added bonus, in the right upper corner of each panel, is inserted a smaller cartoon, an inch square, so that when the book pages are “flipped rapidly,” these insertions create a “movie” of Popeye delivering a sock to the jaw of King Smacko. So, the book’s intended audience is a conundrum, even more so considering the problems inherent in weighing the differences of the expectations of 1930s or 1940s readers with those of readers—adult, pre-teen, children—of today. Two other factors confound the puzzle. The initial publications of Big Little Books (other publishers besides Whitman put out similar material) predate the Golden Age of comic books (Superman first appeared in 1938*). Like early comic books, the BLBs are intended initially for juveniles, mostly pre-adolescent boys, but actually encompass a wider, adult readership. Assuming that the publishers eventually become cognizant of the inclusive age range of their customers, this would help to explain the apparent duality of the book’s personality. The second factor deals with the origin of Sock.

On the other hand, the format of Sock, the format of all of the Big Little Books and Better Little Books, would be an odd one for mature readers. On the left, with roughly seventy-five words per page, with an extensive use of dialogue, the story unfolds; on the right, with only a small border, the page is taken up completely with a captioned cartoon. And as an added bonus, in the right upper corner of each panel, is inserted a smaller cartoon, an inch square, so that when the book pages are “flipped rapidly,” these insertions create a “movie” of Popeye delivering a sock to the jaw of King Smacko. So, the book’s intended audience is a conundrum, even more so considering the problems inherent in weighing the differences of the expectations of 1930s or 1940s readers with those of readers—adult, pre-teen, children—of today. Two other factors confound the puzzle. The initial publications of Big Little Books (other publishers besides Whitman put out similar material) predate the Golden Age of comic books (Superman first appeared in 1938*). Like early comic books, the BLBs are intended initially for juveniles, mostly pre-adolescent boys, but actually encompass a wider, adult readership. Assuming that the publishers eventually become cognizant of the inclusive age range of their customers, this would help to explain the apparent duality of the book’s personality. The second factor deals with the origin of Sock.

This book is both a compressed and expanded version of Segar’s Popeye newspaper dailies that were published between April 5–June 26, 1937, although in the newspaper the adventure continues, with an additional subplot, until August 28 of that year. Newspaper funnies are read by everybody, so it would not be surprising to find that a book based on the dailies would contain adult elements. The compression of the story is the result of the size of a BLB; some volumes are slimmer, but the maximum page count is, like Sock, 432, and that explains the peculiar abruptness of the book’s ending: the publisher basically just runs out of pages. The expansion is the result of the transition from a comic strip using balloons with dialog and exaggerated font for sound effects (Segar rarely uses expository material in his cartoons), to prose, using selected panels from the dailies, with captions beneath but with the dialog balloons removed, as illustrations. Sound effects are retained. This transition, with its resultant prose-cartoon hybrid, should pique the interest of semioticians. Count the ways a story can be told. Is there somehow a shade of difference in meaning or intent between text comprised of all uppercase letters encircled by a talking balloon, and straight prose using combined upper- and lowercase characters, correctly punctuated? It feels intuitive that a cartoon format, talking balloons with their tails pointing to the speaker, carries less intellectual weight than the use of the traditional building blocks of words, sentences, paragraphs and chapters, but there is something positive to be said for the immediate punch that the four or five panels of a daily strip, with their talking balloons and fundamental ink drawing, allows. A BLB, however, manages to carry its weight satisfactorily, and the hybrid works. One way it works is to present to the reader the story in one large bite, easily digested in one sitting, rather than the adventure being drawn in small slices over weeks and months. As said, the drawings are from the dailies, and, too, the dialog on the prose side of the book is lifted virtually word-for-word from the comic strip, but exposition and embellishments are added so the story more readily flows and manages to achieve a heightened literary mien. Sock has become a curious artifact; BLBs today sustain a presence in the collectables marketplace.

And what of the content? Segar is a gifted cartoonist, able to convey nuances of emotion with a subtle stroke of his pen. The backgrounds stand generally bare, but, when needed, the houses and trees are drawn with a quick but accurate hand, occasionally admitting to the delicacy of a fine arts ink drawing (his Sunday strips are somewhat more detailed, and the interiors in these would appeal to a Robert Crumb sensibility). The plot line is basic, but enough twists, reversals, surprises, humorous bits and even, at times, genuine emotional depth keep a reader continuing on. The depression-era “we are all in this together” sentiment adds a layer of wistful appreciation. Even a touch of magic realism comes into play; the Popeye Universe includes supernatural characters, only one of which, Eugene the Jeep, a dog-like, sentient being endowed with uncanny powers and with an affectionate relationship with Olive and Popeye, appears in Sock. And Popeye’s über-human strength after he eats his spinach, his famous twister punch, and his ability to lift a building from its foundation also bring a believable unreality to the reality of the comic. But it is the star of the book—of the newspaper cartoons, the comic books, the animated cartoons and one live-action feature film, played exquisitely by Robin Williams—who ultimately garners the interest and makes the whole thing work.

And what of the content? Segar is a gifted cartoonist, able to convey nuances of emotion with a subtle stroke of his pen. The backgrounds stand generally bare, but, when needed, the houses and trees are drawn with a quick but accurate hand, occasionally admitting to the delicacy of a fine arts ink drawing (his Sunday strips are somewhat more detailed, and the interiors in these would appeal to a Robert Crumb sensibility). The plot line is basic, but enough twists, reversals, surprises, humorous bits and even, at times, genuine emotional depth keep a reader continuing on. The depression-era “we are all in this together” sentiment adds a layer of wistful appreciation. Even a touch of magic realism comes into play; the Popeye Universe includes supernatural characters, only one of which, Eugene the Jeep, a dog-like, sentient being endowed with uncanny powers and with an affectionate relationship with Olive and Popeye, appears in Sock. And Popeye’s über-human strength after he eats his spinach, his famous twister punch, and his ability to lift a building from its foundation also bring a believable unreality to the reality of the comic. But it is the star of the book—of the newspaper cartoons, the comic books, the animated cartoons and one live-action feature film, played exquisitely by Robin Williams—who ultimately garners the interest and makes the whole thing work.

Popeye, even in the most trivialized and formulaic 1960s King Feature made-for-TV cartoons, remains an endearing if rough-and-tumble character. He is “one tough gazookas who hates all palookas what ain’t on the ups and square.” (This is an excerpt from the Popeye theme song, that, by the way, was written by Sammy Lerner in 1933; Lerner also wrote a “theme song” for Marlene Dietrich, “Falling in Love Again.”) The Sailor Man is tough and irascible, but also awash with the milk of human kindness and unexpectedly sentimental; he shows a keen intelligence and is a man of many talents. His strong if rigid sense of righteous indignation, whether within or without the bounds of the law, has forged within him a steely, honest, unshakeable firmness of character. Popeye is a philosopher: “I yam what I yam and that’s all what I yam.” Always he is faithful to his friends, and it is his kindness and sense of justice that propels and grounds the plot and theme of Sock. Popeye’s delectable mangling of English also adds to his popularity. If confronted with an injustice, he becomes “disgustapated;” and at times he loses patience with “frickle dames.” And, please, don’t forget the “pananties and brazoo.” In the Fleischer animations, he keeps up a running muttering monolog that adds much to the comedy (which Robin Williams mimicked nicely in the movie). Popeye’s appearance, in its most classic state, the later Segar Thimble Theatre drawings, and as found in Sock, is a masterwork of humor and poise. They shouldn’t, but the exaggerated forearms, with the anchor tats, work, as do the small pips for the elbows and knees; and the quick fluid strokes of Segar’s pro quill delineating the jaw, the mouth, the eyebrow and the squinty eye make Popeye come alive, indelibly so.

A Sock for Susan’s Sake, depending on your Popeye familiarity, makes for either a somewhat rare literary piece or a pleasing introduction to Segar’s oeuvre. SpeedReaders also recommends the complete Segar Popeye series put out by Fantagraphic Books as well as Sagendorf’s Popeye/The First Fifty Years. Looks like we’re finally finished here: Well, blow me down!

- * In 2012 Popeye was relaunched as a new comic book series. The initial cover, drawn by Bruce Ozella, shows the sailor lifting and smashing a car against a rock, ala the cover of Action Comics #1, Superman’s debut—an adept, cunning tribute.

Copyright 2014, Bill Wolf (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter