The Car: The Rise and Fall of the Machine that Made the Modern World

by Bryan Appleyard

by Bryan Appleyard

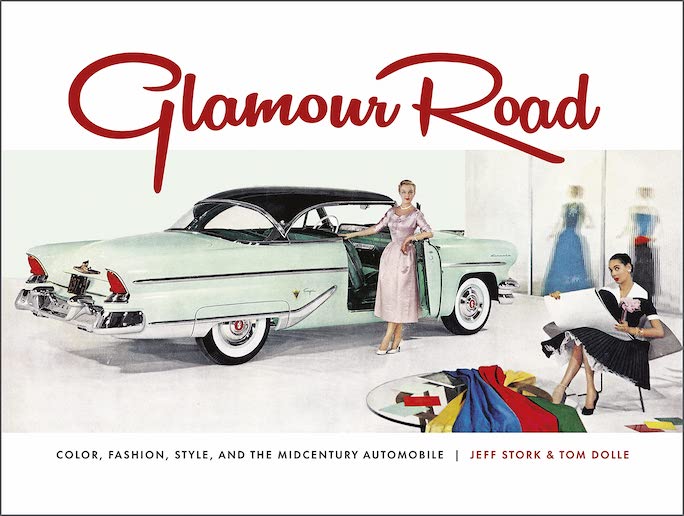

“Killing children in the name of a stylistic superfluity was not a good look for Detroit. The underlying brutality behind the glamour of the fifties’ aesthetic was being exposed.”

—Bryan Appleyard, on a child killed by the tail fin of a ‘61 Cadillac

Even if you’re a Dodge Ram-driving good ol’ boy from Turkey Scratch County, you can’t deny that the internal combustion engine is drinking in the Last Chance Saloon. Times aren’t so much a-changing as having a-changed already, with Tesla the new GM and with no smart college kid wanting to be seen dead or alive in a Dinosaur V8. With a zeitgeist like this (they speak of little else in Turkey Scratch) I suspect Bryan Appleyard’s book will not be the last farewell to the machine that changed the world, originally for the better but latterly for the worse.

Appleyard is an award-winning British journalist whose normal platform is The Sunday Times but this self-confessed car nut (his words) has written a hugely readable book on the rise and ongoing fall of the car as we know it. From the dawn of motoring in the late 19th century, the car became the machine that transcended its function as mere transport, because it offered pleasure in its operation, endowed status by its performance, and stimulated sexual attraction from its styling.

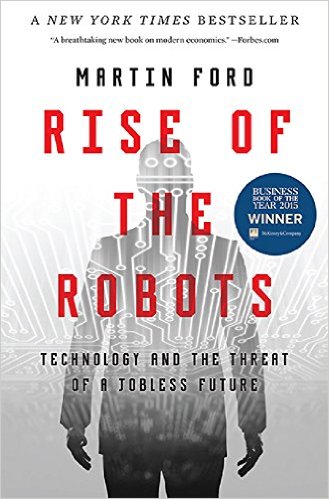

This is not a long book, running to barely 300 pages, but its two parts (“Makers” and “Breakers”) and ten chapters span the history of the car in extraordinary detail. I have been reading car stuff since the ninth grade and I’ll confess that I didn’t expect to learn as much as I did from this book. But I had underestimated the author’s resourcefulness, possibly because most automotive literature is created by car guys who can write—and those two don’t always go together—rather than professional journalists who can do justice to a diversity of subject matter. And diversity is something in which Appleyard excels, as he has already written books on, inter alia, Artificial Intelligence, Aliens, Genetics, and Immortality.

So many authors of books in this genre are too closely focussed on their subject, and so we usually learn about the minutiae of design, engineering innovation, or the stylist’s legerdemain deployed to burnish a car’s DRG (down the road graphics, do keep up). But Appleyard doesn’t fall victim to the myopia that has afflicted many of his peers in this genre. He writes with authority on, for example, precisely what made Major Ivan Hirst believe in the VW Beetle, or how Detroit gradually abandoned the killer tail fin referred to in the opening quotation. But he can also take a long step back in order objectively to discuss the car’s messy origin story or its gradual transformation from liberator to oppressor.

It is significant that the author quotes LJK Setright more than any other author, and rightly so, as I believe that “Long John Kickstart” had no peer in this genre—and he still hasn’t, good though Appleyard undoubtedly is. Not convinced? Read Setright’s Drive On, A Social History of the Motor Car and tell me I am wrong . . .

Appleyard writes with insight and style, and I hadn’t finished page two before I knew I was in the safest of hands. My reviews rarely quote a full paragraph but I must indulge myself here:

“Cars have also remade people. They are the ultimate prosthetics, extending human capabilities across physical and mental dimensions. They allow us to move at hitherto unimaginable speed with unprecedented freedom and to do so in a steel cocoon replete with sophisticated comforts.”

Pretty good, huh? And not the sort of prose you’d encounter in the auto magazines I read.

In 2022 there is obviously an elegiac tone to the book, given the demise of fossil fuelled vehicles and the rise of EVs and the evolution of smart cities—“the ultimate ecosystems for driverless vehicles.” They’ll be safe, clean, and soundtracked by the anodyne hum of Teslas—“the most significant car since the Ford Model T”—as Appleyard rightly believes. But I guess I won’t be alone in mourning the imminent loss of the “you talkin’ to me?” belligerence of a small block Chevy.

I found the sections of the book devoted to the astonishing rise of the American auto industry the most compelling. Once in a Great City, David Maraniss’ forensically detailed book on Detroit is definitive in this field but I greatly enjoyed the passages on Henry Ford and Alfred P. Sloan, in whose hands’ “cars remade the world.” Ford’s alchemy of mass production created a mass market but Sloan “invented and refined the techniques of marketing to the masses” and was also responsible for the definitive credo of the auto industry—“The business of business is business.” I have long been a disciple of Colin Chapman’s “add lightness” mantra, and while I knew he was adhering to aeronautical practice, I didn’t know he was also applying a core principle of Henry Ford. These words could have been Chapman’s, perhaps uttered about another all-conquering race car. Except they weren’t, they were Henry Ford’s, and from half a century earlier: “Fat men cannot run as fast as thin men, but we build most of our vehicles as though dead-weight fat increased speed.”

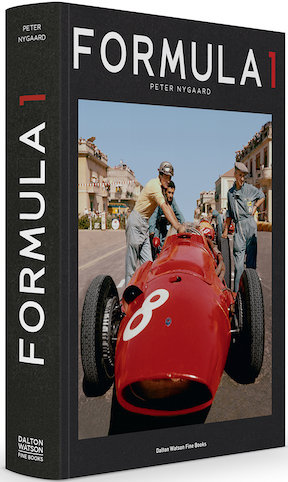

It is a testament to the author’s skill that he has covered so much ground, and in so much depth. From the seismic shift in consumer attitude triggered by Ralph Nader’s campaigning, to a celebration of the Japanese Kei car, to the iconography of fatal car crashes (see also Stephen Bayley’s wonderful Death Drive: There Are No Accidents) the pace is relentless. But the book isn’t perfect, and I found it baffling that no real mention was made of motorsport, despite its influence on road cars, as well as the enormous following enjoyed by Formula One and NASCAR. There are also a number of inconsequential but irritating errors that should have either been picked up by the editor, or not made in the first place. Such as? Inter alia, the reference to a Ferrari 488GTB’s top speed as being 400 kph (actual Vmax 335 kph), a Bugatti Royale’s length being stated as an unremarkable 4.3 meters (actually an extravagant 6.4 m), MLK’s death being quoted as having occurred in 1967 and, more tritely, the New Beetle’s lifespan being stated as between 2011 and 2019 (it was actually 1997–2011). But I’ll forgive Appleyard the latter for his wonderfully Dickensian description of the Beetle: “It was the best of cars; it was the worst of cars.” But despite the author’s expressed love of his subject, there are some clues that suggest his relationship was more of a fling than a marriage. Come on, what car guy would conflate “marque” with “model” or make an otiose reference to “Post War” Ferraris? (They all are, Bryan.)

I’m nit-picking, because that’s what critics do, but trust me, this is a terrifically readable and enjoyable book. It should be read by every car guy/gal whose interest extends to what cars mean as well as what they are. But, if you buy the book, and you really should, make sure Internet access is easily to hand, because you are going to need it, a lot. The book is sparsely illustrated but the wealth of references to the more obscure models means that a Google image search is an essential learning aid. If, however, unlike mine, your mind’s eye can visualize a Toyopet, a Series 62 Cadillac, Lancia Trikappa or—especially—a Graf & Stift 28/32 PS Double Phaeton (in which Archduke Franz Ferdinand made his last journey) your read will be uninterrupted by frequent interrogation of your iPhone.

I conclude with another quotation which encapsulates the enigma that lies at the heart of the machine: “Cars amplify human capacities for good or ill.” I can’t disagree—can you?

Copyright 2022, John Aston (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter