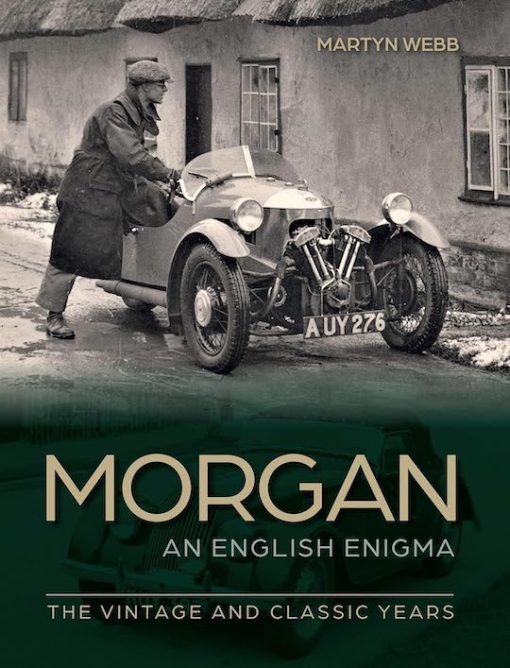

Morgan – An English Enigma: The Vintage and Classic Years

by Martyn Webb

by Martyn Webb

“Industry experts have predicted Morgan’s demise with monotonous regularity and the perceived wisdom has often been that the company could not possibly survive in competition with the big manufacturers. Yet survive it has, confounding the experts and delighting devotees around the world.”

Firstly, a confession; your reviewer hasn’t ever owned a Morgan, and his experiences are merely as passenger and occasional driver of friends’ four-wheelers in England and New Zealand. Over 54 years ago, in September 1969 my brother and I visited Britain for the first time and armed with a letter of introduction from the Service Manager of the British Motor Corporation, Arnold Farrar late of Riley (Coventry) Ltd, to their Competitions Department at Abingdon, we presented ourselves. The large and obviously ex-British Army Security Bloke was dubious; the Motor Show was next month, and everything was secret, so we gave up and slunk away. It was ironical that their “secrets” were the complete lack of innovation that year and the final killing of two long-established marques which had fallen into BMC’s clutches, Riley and Wolseley.

An Ektachrome photo taken by your reviewer at the Morgan factory in September 1969.

A few days later our rental Vauxhall Viva was roaming the tiny roads of Worcestershire, and we noticed a sign pointing to Malvern Link; Morgan! And followed by a, “We’ve come a long way, and please may we have a look at the Works?” “I’m sorry, it’s Friday afternoon and we don’t have anyone to show you around, but please feel free to wander where you like, and ask any questions of the staff”, said the attractive young lady who brightened the very dark wood in the office. We did just that; the brightly finished orange, green and red cars destined for the Motor Show were proudly pointed out to us, and the cheerful bloke sitting on a chassis while installing shock absorber bushes with a rubber hammer commented, “They haven’t changed much, have they?”

Author Martyn Webb has been the company’s archivist since 2009 and lives less than a mile away, and he owns several Morgans. Trained as an aircraft engineer he switched to the restoration of fine woodwork. All of these factors point to one conclusion: he is the right man to write this book.

The book title includes the word “enigma” but Morgans have always been regarded with a light-hearted affection in my experience; possibly apocryphal tales from the VSCC Bulletin like the Three-Wheeler driver who “lost it” coming down one of the steep, greasy and cobbled Glasgow streets which converged. He came to rest at the feet of the policeman on point duty. “Where do you think you’re going?” “I don’t know; where did I come from?” Or, before they were banned from carrying passengers at Brooklands, the driver asking the other occupant after the accident if he could get out? “No, and I’ll tell you something else. When I can get out I’m not b….. getting back in again!”

The book title includes the word “enigma” but Morgans have always been regarded with a light-hearted affection in my experience; possibly apocryphal tales from the VSCC Bulletin like the Three-Wheeler driver who “lost it” coming down one of the steep, greasy and cobbled Glasgow streets which converged. He came to rest at the feet of the policeman on point duty. “Where do you think you’re going?” “I don’t know; where did I come from?” Or, before they were banned from carrying passengers at Brooklands, the driver asking the other occupant after the accident if he could get out? “No, and I’ll tell you something else. When I can get out I’m not b….. getting back in again!”

By 1969 the Plus Eight had supplemented the 4/4, and the use of Rover’s ex-Buick 3.5L V8 had extended the marque’s appeal; there was already a healthy waiting list. Brother John later paid a visit to a London dealership that had just taken delivery of a new bonnet (hood), which came with instructions to trim the aluminum to suit the car under repair.

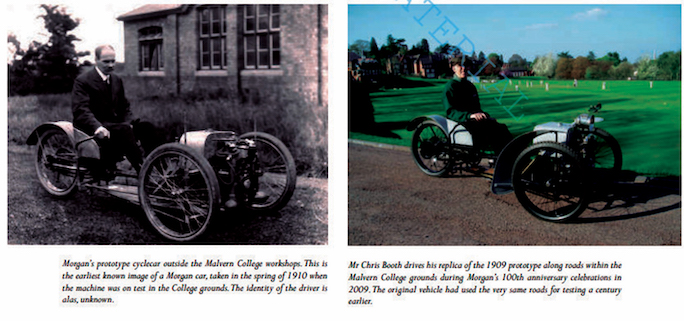

Sixty years before our experience, H.F.S. Morgan (1881–1959) established his motor workshop after experience as a draftsman with the Great Western Railway Company, with financial help from his parents who had brought some capital to the “living” of the Anglican parish where George Morgan (1857–1936) was Canon.

Sixty years before our experience, H.F.S. Morgan (1881–1959) established his motor workshop after experience as a draftsman with the Great Western Railway Company, with financial help from his parents who had brought some capital to the “living” of the Anglican parish where George Morgan (1857–1936) was Canon.

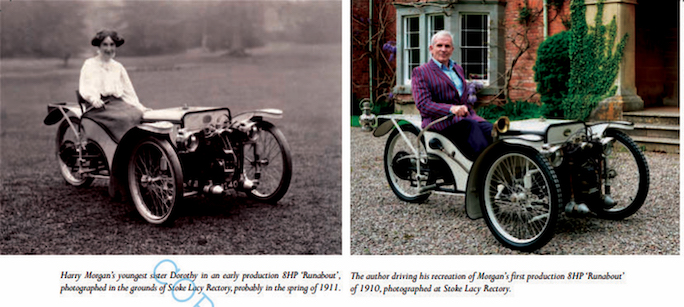

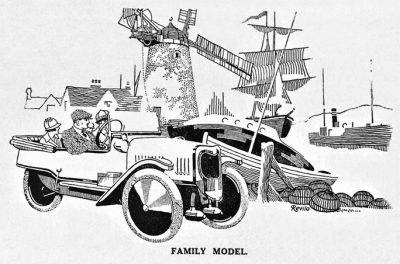

Webb has previously written Morgan, Malvern & Motoring (also Crowood Press, 2008) and his new book goes exhaustively into the history of the Morgan marque while emphasizing the “family” aspect of the firm. One of many delightful images in the book shows his entire family aboard the prototype Family Runabout in the autumn of 1918 (below); Harry and Ruth, their daughters Sylvia, Stella and Brenda with their Nanny astern, and the infant Barbara (Bobbie) in the safety of her mother Ruth’s lap in front. The next year Peter came along, and he is present until Webb concludes his history before the current era when family disputes have changed the Morgan company.

Malvern was then, and remains, a cultural center, very aware of the presence of the composer Edward Elgar’s legacy. During the 1934 Malvern Festival, Brenda Morgan met a young Australian actor at the Malvern Baths. He wanted to get to know her better, but the surely prescient H.F.S. forbade further contact with Errol Flynn (1909–59) then at the start of his movie career. That is the sort of detail that was available to the author, along with an utterly amazing collection of images.

Ruth Morgan, herself a clergyman’s daughter, seems to have felt uncomfortable with the prospects for their daughters, and initiated the family’s move to faraway, but close to London, Maidenhead in Kent. Daily factory running was left to the trusted Works Manager George Goodall, and H.F.S. drove the 300-mile round trip every week and as otherwise needed, in his Derby Bentley.

Reverend Morgan kept up a lively correspondence in the motoring press, and as well as his ecclesiastical duties was a keen artist and photographer. Many of the excellent photographs in the book show smiles on faces of family and factory staff; are there some taken by him?

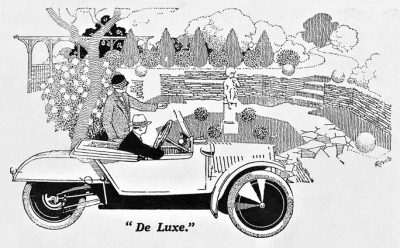

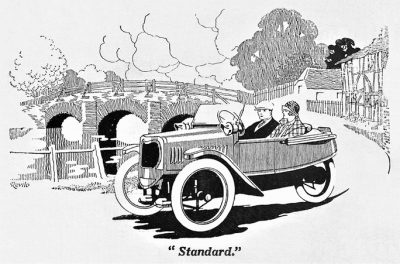

The simple design of a V-twin engine between sliding-pillar independent front suspension with chain drive to a single rear wheel, tubular frame with bodywork for venturesome occupants somewhere between, and a weight of under 400 pounds made for an attractive prospect. By 1912, the fashionable Harrods store offered a two-seater for £92-10-0, which translates to $36,000 one hundred and twelve years later. At the Olympia Motor Show in 1913 more than 700 orders were taken, along with 150 for their French agents, and although land for an expanded factory had been obtained, Morgan and his workforce of 70 faced an embarrassing challenge to meet demand.

Separate chapters cover competition events, always important to Morgans, design and factory processes along with family and relevant social history.

In the early days a minimal wooden body frame, suitably “blackened”, was covered by simple panelling in steel, and finished in paint and varnish by brush in gray, red, blue, green or purple, with other colors incurring an extra £2. As the book finishes with the new Rover 3.5L V8-engined Plus 8 in 1968, this description was mostly still applicable. The timber used was and is Ash sourced from Belgium, with the occasional metal fragment from two wars ready to snarl up a tool.

The V-twin engines fitted were variously J.A.P. or British Anzani, side or overhead valved, driving through a simple bevel-box giving two speeds until 1935, when an o.h.v. Matchless engine was available with three speeds. In that year the 3-wheeler was joined by the 4/4, the additional rear wheel requiring minimal extra design work, with quarter-elliptical rear springs, later semi-elliptic with the rear axle mounted atop the chassis rails. A simple ladder frame of Z-section form had supplanted the original tubes, and was brazed up by the craftsmen in the Morgan factory until they arrived fully built up by Rubery Owen from 1934, along with proprietary Magna wheels, Girling rod brakes, and separately mounted gearbox by Henry Meadows, later replaced by the ubiquitous Moss brand. It still carried the sliding-pillar front suspension, while the migration of its necessary lubricant to the front tires remained a feature, or perhaps a bug, of a Morgan.

The 4/4 engine was a 4-cylinder Ford or Coventry-Climax producing 20 or 23.5 bhp, the decimal point being significant in providing, ahem, sparkling performance from a weight of under 1,500 lb.

As the Great Depression bit and the list price of the base model fell to under £200 with a production of about twenty cars a month, annual losses were able to be absorbed by H.F.S. Morgan’s considerable capital resources; the care-free days of the cycle-car boom were long gone. His political views were strictly pacifist along with a strong regard for his workforce, and the threat of what seemed to be the inevitability of war, along with work manufacturing munitions as a “shadow” factory to the Coventry-based Standard Company, we can only imagine over eighty years later. The Morgan factory took the form of seven “bays” or adjoining buildings accessed by a common driveway, and after the fall of France and the evacuation from Dunkirk in 1940, two bays and a tent village housed the injured soldiers. The factory, with the diminished workforce left after volunteers for the armed forces had departed (of course Morgan had guaranteed their jobs on their return, as he had done 25 years earlier) were also involved with the experimental work at Farnborough and with Alan Cobham’s aircraft in-flight refuelling initiatives.

When peace came it was accompanied by a bleak austerity imposed by the newly elected Labour Government as they sought to rebuild a shattered country. “Export or Die” was the mindset, with a shortage of materials and a Purchase Tax of up to 2/3 of the price of a car. Morgans had their proven design, offered better value than their competitors, and their small production rate suited the times, with demand exceeding supply.

The three-wheeler “F-type” was phased out in 1947, and Peter Morgan was given the task to develop a more powerful design, to be called the “Plus 4” to accompany the 1172 cc Ford engine 4/4. Cordial relations had always been achieved with Sir John Black, the head of Standard Triumph; in his early days he had done some drawing work for Morgan. The difficulty Black and his team had in developing their postwar sports car led to his attempting to buy the Morgan company, but H.F.S. declined the offer. Standard’s new 1850 cc Vanguard engine became the power for Morgan’s new model, with the body and chassis widened and lengthened by two inches while maintaining an overall weight of 1700 lb.

The engine used in the Plus Four had its origins in a low-compression application for the Ferguson tractor. Conventional push-rod overhead valves sat in a cast iron head, while the iron block had “wet” steel cylinder liners with effective cooling for the bores, and the engine size could conveniently vary with the 1991 cc version suiting competition outings, and up to 2.2 liters. The engine survived into the 1980s when Triumphs were built in India. By this time the flat radiator had been replaced by a fencer’s mask-like grille, brazed up at the factory by the same workers who no longer had to braze up the Z-section chassis rails. This was the final stage in the evolution of the Morgan as Martyn Webb concludes his history.

The only thing he hasn’t explained to your reviewer’s satisfaction is the “enigma” part of the book’s title. There is a page of bibliography, two pages of index, and another of acknowledgments, and it all makes for a fine book.

Won the 2024 Royal Automobile Club award for “Books about motor cars and motoring, costing no more than £50.”

Copyright 2024, Tom King (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter