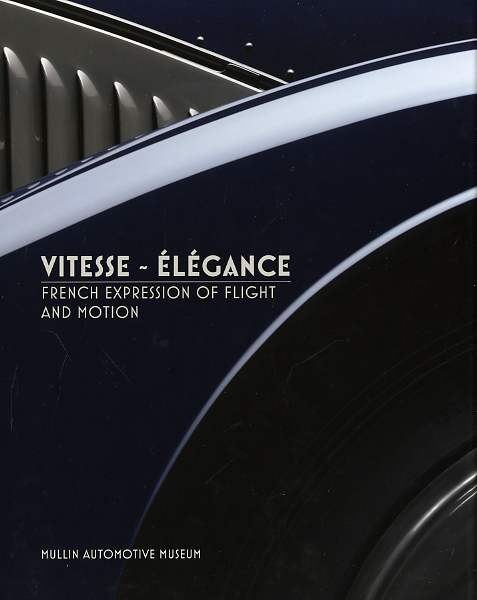

Vitesse~Élégance: French Expression of Flight and Motion

by Serge Bellu, photos by Michael Furman

by Serge Bellu, photos by Michael Furman

This third (and final?) book in the series on the Mullin Automotive Museum is thematically the most difficult yet because it seeks to establish a greater frame of reference than the previous two books for the often exotic French approaches to applied art and science. These two disciplines don’t often play well together and the form/function debate is no less taxing than the chicken/egg conundrum.

Since this is a book about a specific collection it obviously revolves around specially commissioned photos. And in any book that involves photos by Michael Furman, the writing, no matter how good, plays second fiddle: important, with a voice of its own, but not setting the tone.

That Furman is also the publisher is not so that he can push his own photos but because it is the only way he can assure quality, the lack of which being what got him into publishing his own books in the first place. It cannot be said often enough or loudly enough that Coachbuilt Press is not only in the small top tier of premium-quality publishers but occupies a singularly elevated spot because Furman produces his books in the US. The point here being that even with high labor costs he can produce books of superlative quality, and in small quantities, at a price that shows how woefully out of line so many other publishers’ prices are!

The reviews of the other two books began with the writing but this time we shall reverse that order, for reasons that will become clear later. If you don’t already have those other two books: your loss! Better get them while they’re still available, not only because they are fabulous but because they make a “virtual” visit to Mullin’s museum much more practical than a real one: the place is open only a few days a month.

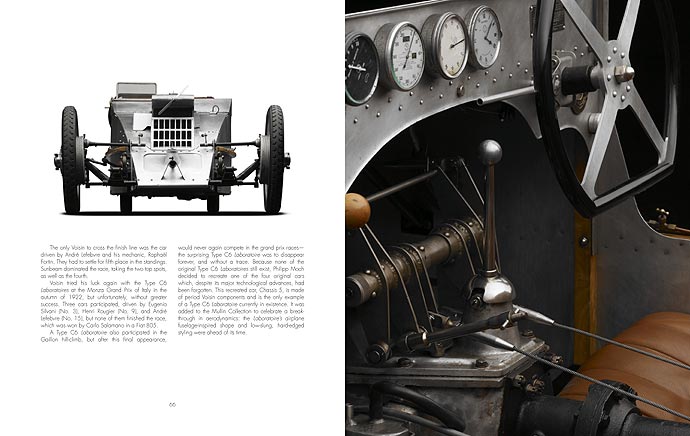

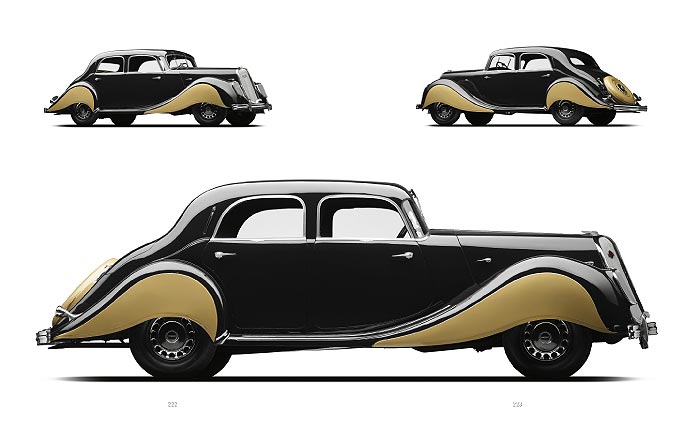

Of course, beholding a car in person, in three dimensions, is an essential aspect of its impact but the photos really do reveal more because reproduced against a white background they remove all the visual noise of the display setting. Likewise the text, in this book more so than in the other two, draws attention to details in the coachwork you might not ever notice on your own. In fact, pondering the design commentary may well raise your game the next time you’re at a concours and wonder just what it is that makes a car special.

As before, each of the museum cars is illustrated with several pages of Furman photos and, as relevant or available, period illustrations of the car (photos, coachwork or technical drawings, even brochures etc.). The studio photos have that reach-out-and-touch-it realism and different textures are rendered accurately. The colors of many of the vehicles in this book are really not easy to shoot—just try capturing different shades of black (glossy paint, matte wheel wells, dull tire rubber) in one set-up without making foul compromises!

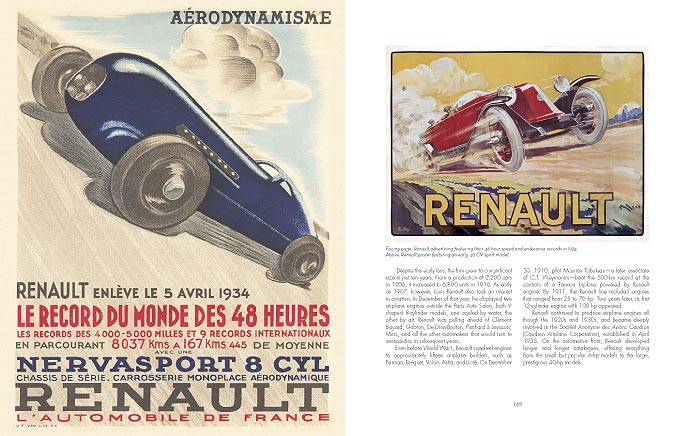

Now, the text. The key premise in this book is that the cars of this period, especially French ones, are the result of a unique moment in time in which aviation themes found application in motorcars, causing a specific tension between design and engineering values. This is true, no argument. Many of the cars in this book, and more so in other ones demonstrate that the French at this stage seem to have been far more willing to lean towards engineering-driven exterior design, no matter how, well, ungainly the car ended up looking. Examine this example:

The challenge of unraveling this thought process was given to Serge Bellu, the widely published French journalist, illustrator, and design commentator (not just cars) and teacher. In addition, the museum’s “editorial staff” is listed as coauthor. While the commentary about the museum cars is inspired, pertinent, and on many counts enlightening there is a certain lack of precision in the 40-page introductory material, whose brevity simply may not lend itself to giving everything its due place, from commerce to fine art to music to architecture. To be clear, nothing here is wrong but the reader who is new to the era and its complex interplay of many factors will not get a fully nuanced picture.

Consider: in the Preface, Peter Mullin identifies as the common denominator for the people whose work is examined here “a curiosity as to how and why things worked.” A reader will have that same curiosity but the book often addresses only the what. Example: post-WWII “the government imposed punitive taxes on custom-built cars.” But why? Elsewhere, the “ultimate obstacle to custom coachbuilding” is said to be “a scarcity of large horsepower chassis” caused by many manufacturers (of chassis?) having gone out of business during the war. This implies that if only there had been chassis, coachbuilding could have continued. But that is hardly the first nor only cause: what about bodybuilders not returning from the war, raw material shortages, rising labor costs etc. etc?

Two key points made are that American influences affected French cars of the period and that after WWI, aircraft makers—and not only in France—had idle capacity and industrial equipment and therefore branched out into automobiles, bringing with them their understanding of aerodynamics and construction methods for achieving both structural strength and light weight. Among the most radical exponents of aero concepts in cars is Gabriel Voisin to whose cars almost a third of the book is devoted. French marque expert Philipp Moch contributed to this section and not only did some of the Voisins in the Mullin museum come from his collection, he built (replicated) them!

Other principal carmakers represented in the Mullin collection that are covered here are Hispano-Suiza, Renault, Panhard & Levassor, Citroën and Peugeot, as is the fabric coachwork of C.T. Weymann, a handful of other collection cars (including a 1938 Tatra as an example of non-French work), and various cyclecars (which, if anything, are even more adventurous than the cars) and motorcycles. Each new section is introduced with general remarks about the maker in question and the period, especially in regards to esthetic and technological stirrings. Each museum car description offers details about the specific chassis and its body, ownership history, and how it came to be in the Mullin collection.

There is a Suggested Reading list but no Index.

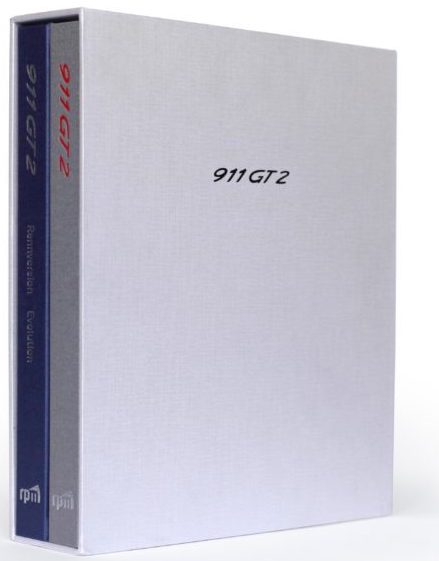

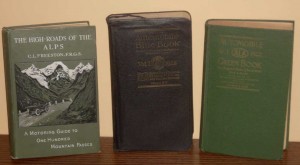

Footnote for our many readers who make books: stand the three books upright, oldest on the left, newest on the right. Observe the book titles lengthwise on the spines: on the oldest book it is set fairly low on the spine, uncommonly low in fact (back in 2010 we assumed this to be necessitated by the “glare”‘ higher up on the spine preventing the use of white type). With each new book the title starts gradually higher on the spine, staggered in fairly even increments. So what, you say? When the series started, three years ago, the designer already had a long-range plan! It is this cleverness, this attention to detail that makes the books Furman and his team produce the benchmark to aim for. (And, dontcha know, there’s room for a fourth title . . .)

Copyright 2013, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter