Studebaker and Byers A. Burlingame

End of an Automotive Legacy

The “Studebaker” portion of the title refers to the decision process and subsequent corporate cost-cutting activities (November 1963 to March 1966) used to justify the continuance or discontinuance of Studebaker automobile production in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. The “Byers A. Burlingame” portion of the title refers to the CEO and President, Studebaker Corporation, who set up the executive decision-making criteria (breakeven or better performance) and eventually made the historic decision to stop production permanently. With the end of its automobile production in March 1966, Studebaker’s 114-year legacy as a builder of reliable transportation and conveyance vehicles (horse-drawn wagons to Gran Tourismo Hawks and baby-blue 2-door Daytona convertibles) ended.

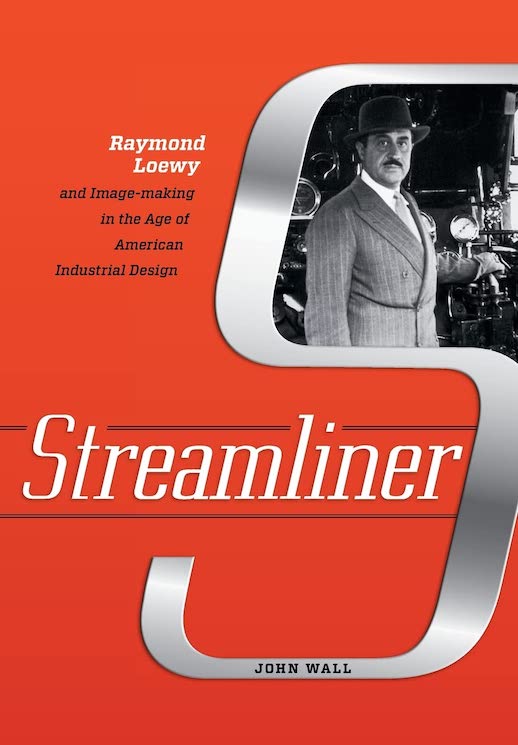

The pace-setting 1962 Studebaker Avanti sports car designed by Raymond Loewy for Sherwood H. Egbert, Studebaker CEO and President (Jan 1961 to Nov 1963), was going to turn around Studebaker’s fortunes and set the world on fire. This is what Loewy’s 1947 and 1953 Studebaker designs had been expected to accomplish. According to Ebert (Professor Emeritus of Economics at Baldwin Wallace University in Berea, Ohio), when Burlingame assumed his new leadership position, board meeting notes reveal “the Avanti had not been a success.”

As Ebert makes clear, the story is convoluted and complex and his book sets the record straight. Based on primary sources (e.g., board meeting notes and letters, executive correspondence, annual reports, and other primary sources), he chronicles the steps taken by management, as led by Burlingame, to attempt to preserve stockholder equity and save the Studebaker automobile from extinction. He also organizes considerable quantitative information to support his analysis.

Although an integral part of his analysis and the data set he uses, Ebert does not discuss in detail the financial aspects of the Avanti sports car program or the other Studebaker divisions. Ebert states the other profitable Studebaker divisions offset the automobile division’s losses. Studebaker was a conglomerate, or diversified corporation, and that’s how they operated. Per a 1966 annual report, the other divisions included appliances, commercial refrigeration, generators, tractors, stud tires and STP (à la Andy Granatelli).

Written from an economist’s point of view and using “for the record” information, Ebert is brief, concise, and to the point.

Following the chronology of events, he simplifies things for the reader by reporting the key kernels of information, and direct excerpts from board meeting minutes. Ebert prefers to use and quote numbers to prove his points. Also, while he reports and threads key pieces of information together, he keeps his commentary focused on guiding the reader from point to point rather than imparting his own views and opinions.

Although based on research at the National Studebaker Museum in South Bend, Indiana, most of the images in the book come from Ebert’s personal collection of Studebaker memorabilia.

This was a fascinating and eye-opening book to read and will help automotive historians understand the complexity of Studebaker Corporation’s business and the decision faced by Byers Burlingame. He had the wisdom to define the “Go/No Go” performance criteria for its automotive division and the courage to abide by the results. Given all the cost cutting and consolidation achieved under Burlingame, this reviewer believes he set a reasonable performance standard, gave Studebaker’s automotive division a fair chance at proving its viability and that his decision was fair.

Copyright 2016, John L. Jacobus (speedreaders.info).

This review appears courtesy of the SAH in whose Journal (March/April 2016 issue) it was first printed.

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter