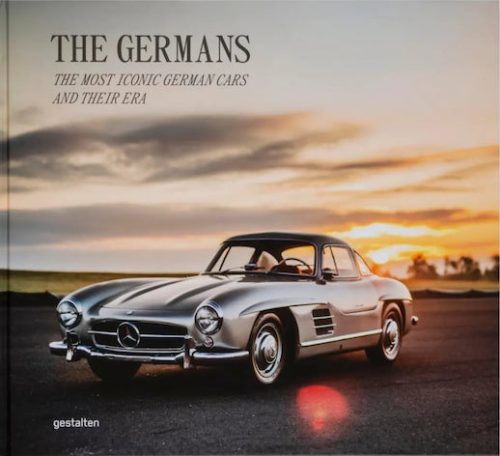

Rudolf Uhlenhaut

Engineer and Gentleman, Father of the Mercedes 300 SL

by Wolfgang Scheller and Thomas Pollak

by Wolfgang Scheller and Thomas Pollak

“According to his grandchildren, Uhlenhaut did not want a biography to be written about him. He could not stand self-promotion or the pursuit of a personality cult, in marked contrast to his long-standing companion, Racing Manager Alfred Neubauer. This modesty had nothing to do with coquetry, but represented Uhlenhaut’s fundamental attitude. One could even say it was part of his personality not to take himself too seriously. He did not want anything private to be known, so he made a conscious effort to live an inconspicuous life whenever he was not at work.”

Thank goodness, Uhlenhaut’s family thought that finally the time was right—the man has been dead for over 30 years—for a proper biography to be written. It is nothing short of odd that such a capable and influential industry figure should have escaped other scribes’ attention. Author Scheller remembers coming across the name as a schoolboy but it wasn’t until years later that professional interests caused him to return to the subject, only to find that there were no sources from which to glean a full picture. So he wrote this book!

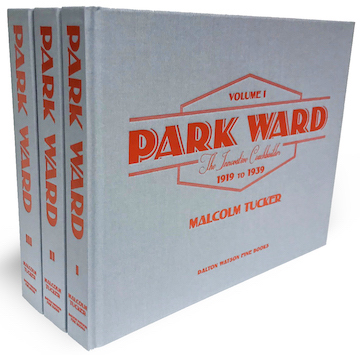

The “driving engineer” as his colleagues referred to this Daimler-Benz lifer most definitely deserves to have his life and his professional accomplishments comprehensively recorded. This book certainly ticks these two boxes, but it is easy to imagine that it could have gone further, deeper. Here the choice of publisher probably is a factor. The English language version is by Dalton Watson, which always and deservedly raises expectations, but it is only a translation of a title first published in German, in 2015, by Heel Verlag. They make pretty books, nice books, pretty nice books but books that don’t really try to reach the level of the archly rigorous reference-caliber Final Word. (Dalton Watson acolytes will now of course point out that there have in fact been instances were DW took an already fine foreign book and made it better still by giving it “the treatment;” see cf. Delage, France’s Finest Car) However, credit where credit is due, the German original did win a first prize at the 2016 ADAC Autobuchpreis in the “Biography” category.

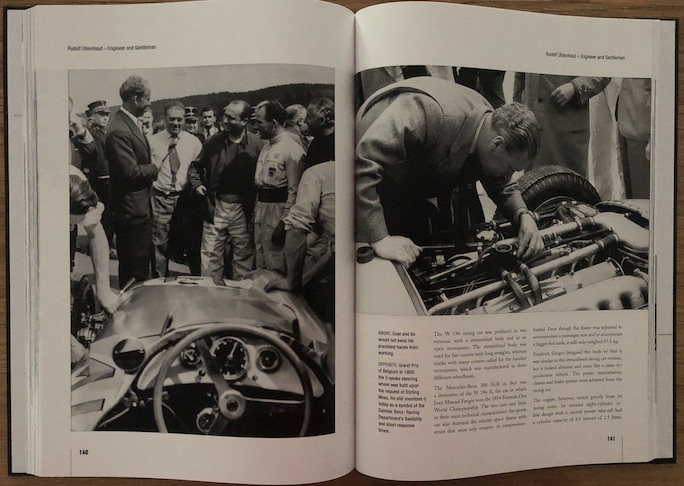

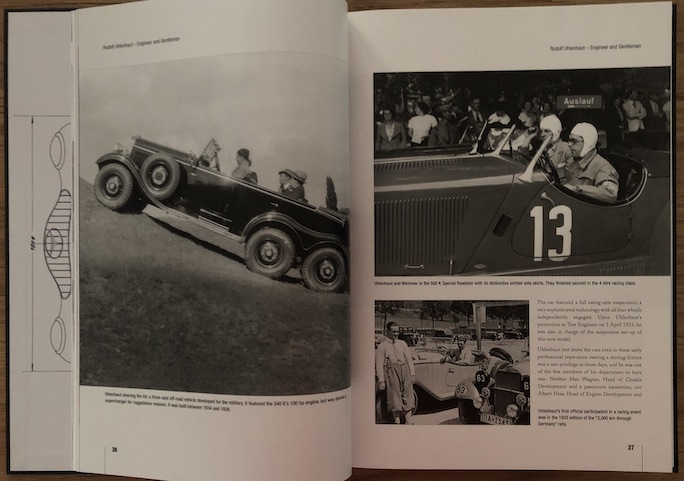

To return to the “driving engineer” moniker: Americans, who pretty much consider possession of a drivers license their birth right, will be vastly baffled by the fact that Uhlenhaut (1906–1989) was one of the few people at D-B who had one in the 1930s—even department heads, or, for that matter, the chairman of the Board of Management of Daimler-Benz AG didn’t have one! So, while wringing his projects out on the road may have started out of necessity, getting behind the wheel became a career-lasting approach to gaining first-hand knowledge. And he was a good driver, so good that he raced/rallied competitively and even showed one Juan Manuel Fangio a thing or two.

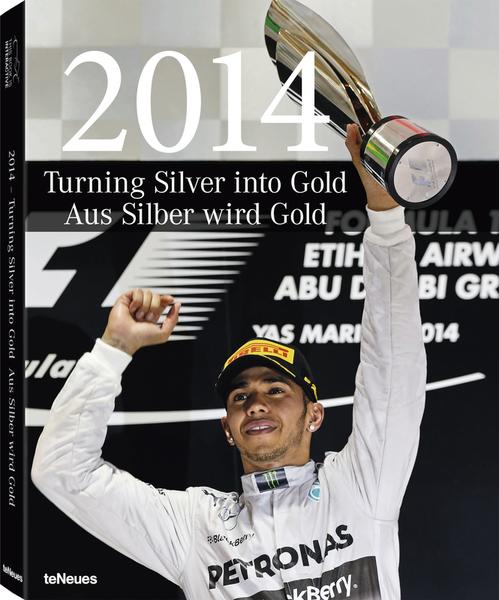

The book title singles out the now legendary 300 SL but it might just as well have mentioned the iconic 230 SL “Pagoda” models, or the C 111, or, much more important in the larger scheme of things, the Silver Arrow race cars that dominated automobile racing in the late 1930s and restored Mercedes to the top tier of the big names in motorsports. All these cars and many more, including commercial vehicles (even aero engines and jet engine parts) are discussed here. The most remarkable aspect of this career is how quickly Uhlenhaut advanced, going from test engineer fresh out of university to Head of Passenger Car Development.

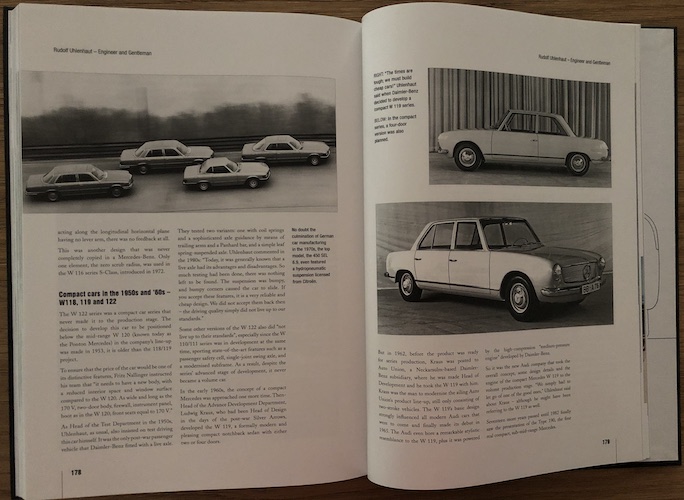

“Times are tough; we must build cheap cars!” There’s a reason this W 119 looks more like an Audi than a Mercedes.

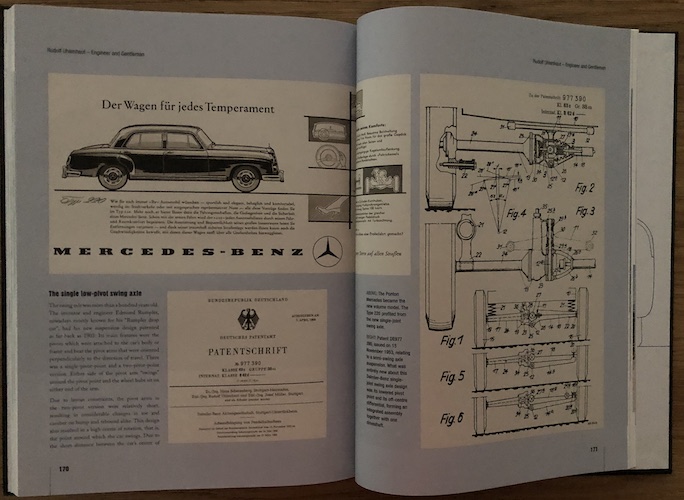

From family tree to retirement, interspersed by four “Technical Progress” chapters, the book touches on all the relevant way stations and gives a fluid, cohesive overview. To put it differently, almost any one subject area could have been meaningfully examined at a greater degree of magnification—and the “trouble” with such long-overdue books is that once one is out, there’s almost no chance the subject will get revisited any time soon. Engineering types will probably find the treatment of some of the technical topics perfunctory (the whole swing axle business in particular), although it must be realized that Scheller was aware of his own limitations in that area and brought on a mechanical engineer as co-author.

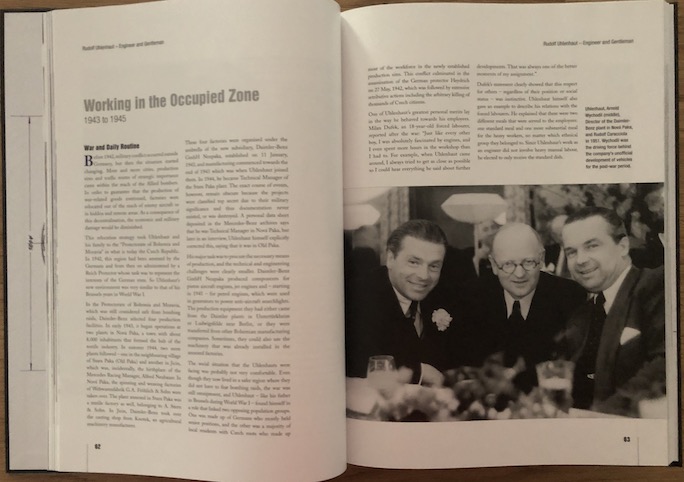

Now, this is a book written by Germans about a German protagonist (yes, yes, Uhlenhaut was born in London) who was active at a time that still gives Germans palpitations—the Nazi era. There is no arguing that industrial concerns were faced with pressures to which there are no clear-cut solutions. Uhlenhaut’s activities during and after the war, and the postwar de-Nazification investigation are mentioned, but there’s not much detail, and some will wonder if Uhlenhaut really was the “unpolitical man” (outside of unavoidable party membership) he is portrayed as.

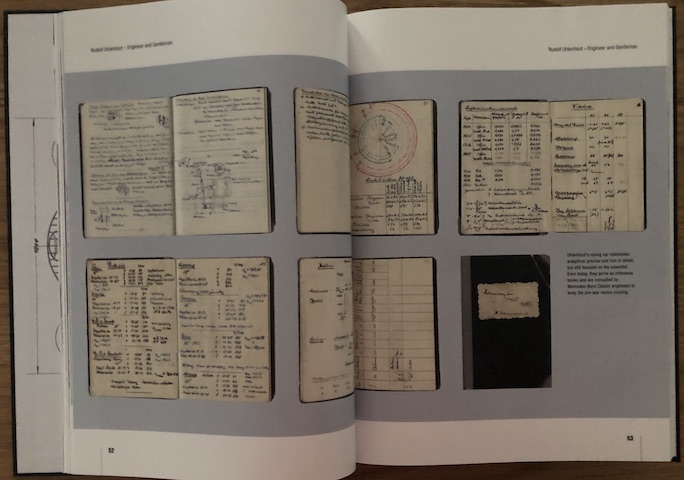

The book draws on interviews with principals and contemporaries, some, especially the ones of family members conducted by the authors (sources are listed; there is no index). Many of the photos are previously unpublished, and reproductions of pages from Uhlenhaut’s notebooks will be immensely interesting to anyone who can read German (his notes, below, are still being consulted today by the Mercedes Museum staff).

Considering that Uhlenhaut himself did not leave much of a papertrail, and that due to circumstances (country-hopping in his childhood, war) certain particulars remain undocumented, or undiscovered this book does offer a good summary and overview.

Incidentally, the German original (ISBN 978-3-95843-150-8) was square (ca. 10 x 10″) whereas this version is 9 x 12″ which makes for less crowded pages.

Incidentally, the German original (ISBN 978-3-95843-150-8) was square (ca. 10 x 10″) whereas this version is 9 x 12″ which makes for less crowded pages.

Copyright 2020, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter