Niki Lauda: The Biography

“Yes, they sent a priest. So what?

There was nothing I could do about it. To live, I had to stay awake. I stayed awake. I shall drive on Sunday.”

—Niki Lauda – Monza, September 1976,

six weeks after his accident at the Nürburgring

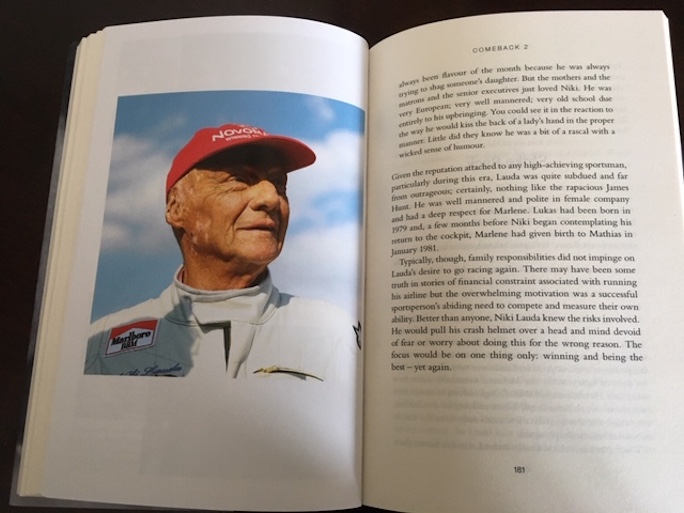

It all depends on your age. If you are under fifty, Andreas Nikolaus Lauda (1949–2019) was the straight-talking guy with the red cap and the livid scars who was a constant presence in the Mercedes pits, and friend and mentor to their driver Lewis Hamilton. If you are older, you know that Lauda’s Mercedes role was his part-time retirement job, a footnote to a storied career as a three-time world champion and, arguably, the only Grand Prix driver who made a successful comeback to the sport after premature retirement.

There are two big challenges in writing this book—the first is that not only did Lauda himself write several biographical works, including To Hell and Back (1985, new edition 2020) and Second Time Around (1984), and the second challenge is that Jon Saltinstall documented every single event in which Lauda completed in Niki Lauda – His Competition History (2020). Formula One journalist Will Buxton also devoted a chapter in My Greatest Defeat (2019) to the trauma Lauda endured in dealing with the aftermath of the demise of his airline in 1991. Can Maurice Hamilton find fresh vistas in this already familiar landscape, and can he do justice to the story of a man defined not only by his courage but also by his unique personality? After all, Lauda was the man about whom veteran journalist Nigel Roebuck said “I have never met anyone who reminded me of him.”

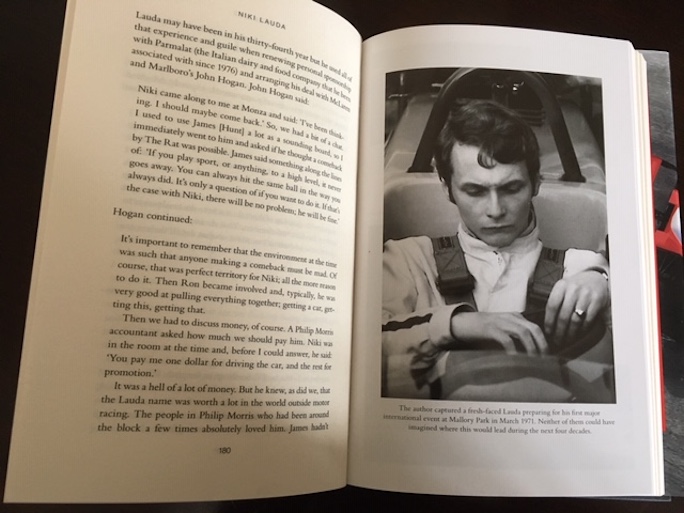

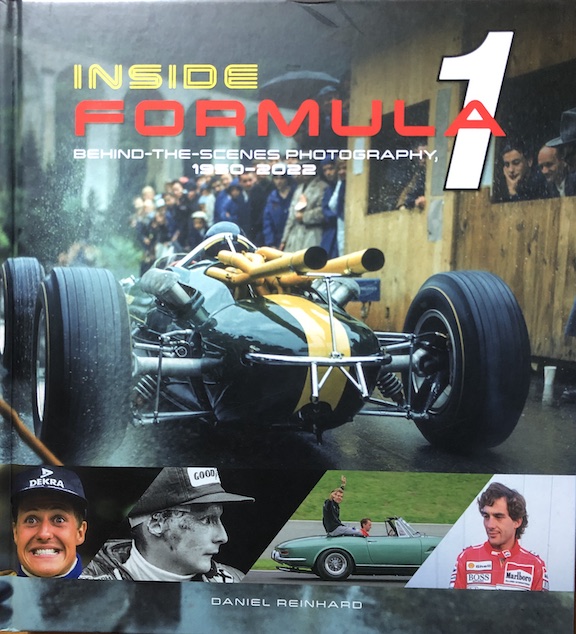

If anybody is equipped for the task of writing about such a sui generis figure, Hamilton should be. Like your reviewer, he first encountered Niki Lauda at the Mallory Park Formula Two meeting in March 1971 but (unlike your reviewer) Hamilton wasn’t too shy to take a close-up photograph of a fresh-faced Lauda on his debut into the big league. Hamilton went on to make motorsport journalism his career, attending more than 500 Grands Prix and getting to know Lauda well. Niki Lauda – The Biography may aspire to become the definitive work on its subject, but I would make the proviso that it is best read with Saltinstall’s superbly researched book also very close to hand. Hamilton recounts Lauda’s career in 36 chapters and 372 pages, just over half of which apply to his career as a driver. The book also includes a small selection of photographs, most in color but all of a small scale. Once again, it is to Saltinstall’s book the reader must turn if images are desired to supplement the narrative.

But this book is the story of Niki Lauda, not an illustrated history, and Hamilton tells the story well, with the polish that comes from decades of experience. Lauda’s career arc will be familiar to many readers, but so extraordinary is his story that it bears retelling. Because, unlike Peterson or Stewart, whose stars had shone so brightly in lower formulae that success in Formula One seemed inevitable, Lauda was a driver in whom few had seen any portent of greatness. His first season in the March 721 had seemed only to confirm suspicions that he was destined to be yet another driver whose time in Formula One was to be unmarked by success, and that he would join the long list of “never weres,” containing names like Loris Kessell and Dave Walker. Hamilton recounts how it was the badly designed March car, not Lauda, which was lacking and how, in late 1972, Louis Stanley’s bullshit about his BRM team’s prospects was matched by Lauda’s fairy story about being able to afford to buy a drive for the 1973 season. It did come good, of course, and Lauda was quickly eclipsing his team mate, Clay Reggazoni, the man who had been good enough to win for Ferrari at Monza in 1970. The glory days for both men came in the 1974–76 seasons when they drove for the revitalized Scuderia Ferrari in the glorious 312B3 and 312T.

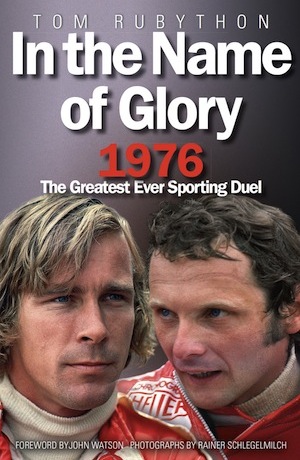

And then came the accident that transformed not only Lauda’s appearance but his status. In July 1976 he was a World Champion, but largely unknown by the general public, as Formula One was a long way from becoming the global brand it is now. But everybody had heard of Lauda by September, including hard-bitten British journalists such as Ian Wooldridge and Harry Carpenter. Neither were known for their coverage of motor racing, yet both were now telling the world about the extraordinary courage of the buck-toothed Austrian who had stared into the abyss only weeks before, but was already back in the car to compete at Monza. Hamilton recounts the events at the Nürburging on 1 August 1976 and their aftermath with forensic attention to detail. The story of how his fellow drivers—Edwards, Lunger, Ertl, and Merzario—rescued Lauda from his burning Ferrari is inspiring but it prompts me to wonder, yet again, why it was only David Purley who stopped to help Roger Williamson at Zandvoort in 1973.

In 2013 Ron Howard’s Rush movie recounted the fairytale conclusion of the 1976 season, with James Hunt taking the championship in the final moments of the final race at Suzuka. The victory was secured after the only man who deserved the championship more than Hunt had withdrawn from the race in the opening laps—Lauda, of course, whose pragmatism was the other victor that day. Next year it was business as usual, with another world championship for Ferrari, then a short, inconclusive period with Brabham before, in 1979, Lauda simply walked away from the sport at Montreal after asking himself “what am I doing here?” And yet, three years later, the Rat (did those prominent buck teeth really warrant that nickname . . .?) was back, this time at the wheel of the carbon chassis McLaren MP4/1B, in a move that risked devaluing his legacy. Because wasn’t it a truth universally acknowledged that comebacks by Grand Prix drivers were triumphs of vanity, one-way tickets to ignominy, serving only to tarnish the glitter of past successes? Even legendary tough guys (and champions both) Alan Jones and Nigel Mansell left the sport with little more than whimpers. But not Lauda, he left with a bang, winning the Dutch Grand Prix at Zandvoort in his final season, his McLaren carrying the number one of the reigning world champion from the 1984 season. Your reviewer was there, high up in the sand dunes above Scheivlak Corner, watching Lauda slugging it out with team mate Prost to win by less than a quarter of a second. It was the last hurrah for both driver and circuit but I suspect its echo will still be audible when Zandvoort redux hosts its first Grand Prix in 2021.

Hamilton uses contemporary quotations extensively in the book and they carry a lot of weight, as you would expect from the living testimony of team mates, confidants, and specialist journalists such as Giorgio Piola. This is all well and good, but hindsight can enable a more focussed perspective to be applied to a biography and yet there is little evidence of such a view being taken. That said, Hamilton’s source material still serves well to reveal the man whose personality was far more nuanced than the cliché of the automaton driver nicknamed “The computer.” Even the casual follower of Formula One knew all about Lauda’s work ethic, intelligence, and brutal directness of expression but it was not until the Lauda Air crash in 1991 that his compassion and humanity came so sharply into view.

“I didn’t care whose fault it was; it could have been mine; it could have been somebody else’s; I just wanted to know” said Lauda. He took on, and wore down, the obduracy of Boeing, the doomed aircraft’s manufacturer, and proved that it was not pilot error, nor the fault of the airline, but Boeing’s alone. How many other airline owners would have said, after the death of 213 customers “I spoke to as many relatives as I could and told them they were always free to call me”? Lauda wasn’t the only motorsports figure to be a pilot (but he had the distinction of holding a commercial rating and sometimes captained his own airliners) but in contrast to some, most notably Colin McRae, whose recklessness cost innocent lives, Lauda the pilot played it by the book.

The book is described as a biography but in some respects it falls short of its ambition. Not only is the author’s own voice mainly silent, but many aspects of Lauda’s personal life are described superficially at best, and some not at all. I wanted to know far more about his homes, his interests, his wives and girlfriends than this book revealed and it was ironic that the person who gave the deepest insight into Lauda the man was Daniel Bruhl, the actor who played him in Rush (Lauda made a cameo appearance at the end of the film). “I’d never come across a man like him . . . there were times when I could not believe what I was seeing and hearing.” Further insight, but extending only to a frustratingly short five pages, comes from sons Matthias and Lukas, in the penultimate chapter. And of Lauda’s widow, Birgit, whom he married in 2008? A single mention, by Gerhard Berger. I expected more, especially when so much of Lauda’s story had already been told in print before his death.

Does this book do Lauda full justice? Not quite—because, despite the dazzling mosaic of impressions from those who knew him, the intimate detail of the full picture remains frustratingly indiscernible. If there is a second edition, there is more work to be done.

Copyright John Aston, speedreaders.info 2020

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter