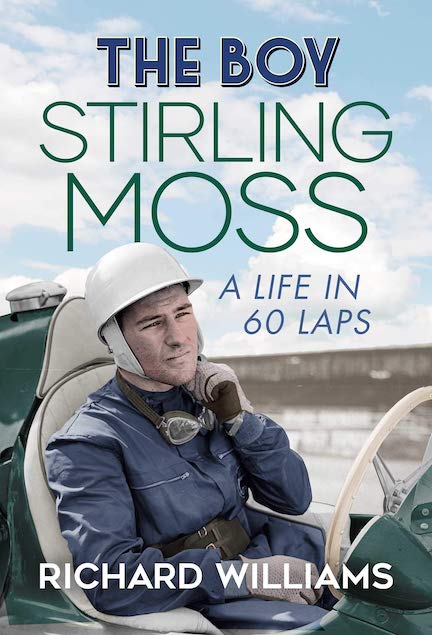

The Boy: Stirling Moss, A Life in 60 Laps

“Who you think you are, Stirling Moss?”

If you had asked me in 2019 if the world needed yet another book about The Beatles the answer would have been “no.” But I was wrong, because Craig Brown’s One Two Three Four: The Beatles in Time was a joy to read. More mosaic than portrait, the book was charming, playful and, by addressing its subject from an oblique angle, it was able to offer delightfully original insights. Sir Stirling Moss died in 2020, making the publication of yet another book about him an inevitability but, as in the case of Craig Brown’s book, it was the author’s reputation and the fresh approach taken to his subject that piqued my interest.

Most people are too young to have lived through Stirling Moss’ career—which ended nearly sixty years ago—but Moss never disappeared from the public consciousness. If you had any interest in motorsport it was inevitable that you would have osmosed all the key details about Moss. And you got to read them all over again in the obituaries, most of which seemed to have been written on autopilot—“the best driver never to win the world championship”, “chasing crumpet”, “at an average speed of 98 mph in the silver 300SLR”, and the predictable reference to the rhetorical question the speeding motorist would allegedly be asked by the traffic cop, “who do you think you are, Stirling Moss?” I really could not have faced trudging through a cobbled together hagiography. However Richard Williams is no opportunistic hack but an author who has never failed to do full justice to his subject. He did so with Ayrton Senna and Richard Seaman and now he has done it again with Stirling Moss, because A Life in 60 Laps is a rewarding, entertaining, and informative read.

This near 300-page book is not yet a(nother) biography but a collection of 60 short chapters (4–6 pages each) on various facets of Moss’ life. It is a kaleidoscope of impressions, aperçus, and personal recollections which enable the book to transcend its genre by covering Moss the man as much as Moss “the greatest driver never . . .”—you know the rest. As Williams adroitly puts it, Moss had become “a one-man emblem of his sport” in the 1950s and some would argue that, in the United Kingdom at least, Moss successfully resisted competing claims for that status from everybody from Hunt to Hamilton.

Williams describes key points in Moss’ career, from early days at Silverstone in 1950 to his famous lunch with Enzo Ferrari at Maranello’s Cavallino restaurant. Of the former occasion Autosport’s editor Gregor Grant prescient words still resonate: “. . . a touch of Rosemeyer, the same fire and certainty that the car was always under control.” Motor racing has always had more than its share of what ifs and, as the fateful lunch with Il Commendatore took place only weeks before the career-ending Goodwood crash in 1962, the reader can’t help but agree with Williams’s suggestion that “surely this was Moss’ opportunity to set the seal on his career.” The book covers, but doesn’t unduly dwell upon, the already well known highlights of the driver’s career—the Mille Miglia (how on earth did Denis Jenkinson condense a 1000-mile route into just 18 feet of notes?), the Mercedes seat alongside Fangio and the extraordinary account of Moss’ record-breaking in the teardrop MG EX 181 in 1956—245 mph in a car powered by a 1500 cc engine of very humble origin. But what I most enjoyed about the book was the period detail and the insights into Moss’ personality.

Moss became the template for the professional racing driver and his influence on his successors is apparent to the present day. He was acutely aware of his own financial worth and he didn’t fail to exploit it, because even decades after his retirement Stirling Moss had become the brand whose endorsement could add glister to any automotive product and any historic motorsport event. His name became synonymous with the devil-may-care insouciance of the postwar era, while his tales of crumpet-chasing were endlessly told and retold, almost as if inviting disapproval from a changing world. During the last three decades it seemed to me that Moss was risking becoming a man defined mainly by anecdote and one who seemed actively to court disapproval by his espousal of dated attitudes, especially those relating to sexual politics and motorsport safety. It is to Williams’ great credit that he has been successful in navigating through the doldrums in which Moss’ reputation risked becoming becalmed by creating a much more vivid portrait of the man behind the brand.

I gained insight into what really made Moss tick from the chapters about his high tech home (“The Pad”), his choices of transport (“‘Mopeds and Minis”) and, especially, from the account of his interview on the Face to Face TV program with John Freeman, “a pioneer in the art of interrogation on the small screen.” What a contrast that was to the scripted gush of Moss’ reception by host Eamonn Andrews on This is Your Life which features a few chapters earlier. Freeman probes into Moss’ life after racing (which was to start barely two years later): “. . . it wouldn’t be what people usually meant by retirement. I can’t relax. I don’t want to relax. I think my friends find it rather annoying at times.” On religion: “I’m religious, in that I think there’s a God. I’m not religious in that I don’t believe in going to church.” The author points out that, eerily, Ayrton Senna was to say almost exactly the same words thirty years later. Perhaps it is an ego thing, with church attendance being something only humble civilians do?

Williams even delves into the trademark Moss wave. I’d wondered whether it was always given out of courtesy, or if it was calculated subtly to demoralize the driver who had just been overtaken. My cynicism was undermined by Williams’ lovely anecdote of a young boy watching the titular Boy in a practice session at Silverstone and wondering to whom the Moss wave was being addressed. “The boy looked around . . . before realising that it was meant for him. The wave made everybody feel good.”

Richard Williams conveys what a very different world motorsport in the Fifties occupied in comparison to its modern counterpart. Fernando Alonso recently received much press coverage simply because he decided to explore the motorsport world outside Formula One’s straitjacket but Moss drove anything and everything—and anywhere. We already know about the Mercs and the D Types, the “ten tenths” majesty at Monaco in the Lotus 18, and so much more, but who knew that in 1951 the man who was already “Britain’s most promising driver” also shared a friend’s Morris Minor convertible in the Chiltern Night Rally? Today’s 23-race Formula One season is demanding but spare a thought for The Mechanic, as the author describes Alf Francis. It is 1956 and in one week Francis towed Moss’ Maserati from London to Modena and then drove back home. Next day he towed a Cooper Bobtail to Reims, and thence to Rouen. His tow car was a Standard Vanguard and when Francis wasn’t driving, he was working on the race cars.

Any Moss aficionado will already have a shelf full of biographies and scrapbooks about the Boy but is there space for one more, can this book earn a place? I think it can, as Richard Williams—a fan of Moss since childhood—paints a picture of the two sides of his subject. One is the patriotic, chivalrous and hugely gifted racing driver whose feats defined an era, and whose failure to win a world championship only burnished his public reputation as Britain’s Golden Boy. The rather less alluring side of Moss was seen in his exploitation of the rules to “steal” victory from Masten Gregory in the last fifty yards of the Cuban Grand Prix, and in the downright meanness that extended to forbidding his then wife Katie from spending her own money. It is possible, I suppose, that some of Sir Stirling’s more vociferous fans might regard this material as tarnishing the man who since his death has been all but beatified. But to this reader such faults served only to remind us that Stirling Moss was much more than the one-dimensional hero some wanted, or maybe even needed him to be. This book shows that his was a much more interesting and nuanced personality than the near faultless icon he had become. Some grit in a reputation’s oyster only serves to elevate the subject of this book. I admire Richard Williams’s bravery in taking this approach— this is a very fine book about an extraordinary man. But let Robbie Burns have the last word: “A Man’s a Man for a’ That.”

Copyright 2021, John Aston Speedreaders.info

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter