Ferrari F40

by Gaetano Derosa

by Gaetano Derosa

“The new car was to be known as the F40 Le Mans. The ‘F’ stood for Ferrari, the ‘40’ for the anniversary it was celebrating. The acronym had been suggested by Gino Rancati, a journalist and an old friend of the Commendatore, and was to be read in English—“Ferrari Forty”—as it was rightly thought that the most important market for the car would be in North America.”

(Italian / English, side by side) See, right away you picked up a tidbit you probably didn’t know. Have you ever heard anyone refer to the car that way? The “Le Mans” bit was already officially dropped before the next public unveil a few months later. That it had ever been part of the name, blessed if not insisted upon by Enzo Ferrari himself, speaks to the car’s hardcore spec that prioritized motorsports potential over creature comforts.

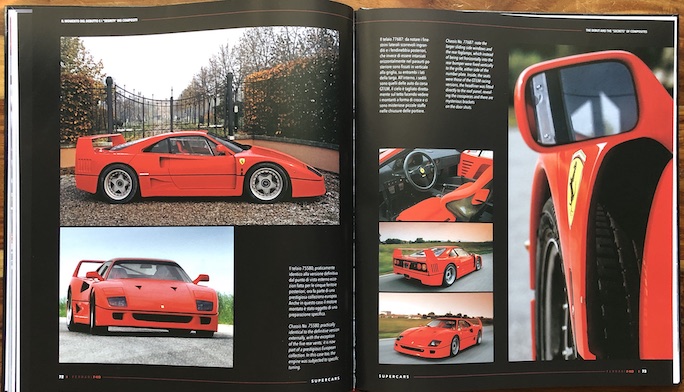

Yes, yes, the Ferrari Forty was only available in red. Unless you are the Royal Family of Brunei (they bought eight, and of course heaps of other Ferraris) or, in the above case, the president of the Italian Ferrari Club.

The F40 occupies an elevated spot in the Ferrari universe, and this book gives a perfectly good account of why that is. It does that by means that differentiate it from others—not that there are a lot to choose from, in fact the only other serious in-depth treatment came out the same year this one did. That there should be two new books in 2022, after years of radio silence, is of course because the F40’s production run ended a nice round number of years (30) earlier. That other book is Ferrari F40 by Keith Bluemel, and they play well together because Derosa dips deep into the well of primary sources such as Ferrari press materials and handbooks/manuals. Such items were never in wide circulation and mostly provided to the press and of course car buyers. They are, for lack of a better word public-facing, which means they are “on message” in a way an internal memo/report would not have to be, and Derosa drawing on them so extensively does mean that his book contains a lot of text that is descriptive as opposed to interpretative. Example: the book tells you “the airconditioning was optional” but it doesn’t tell you that it was utterly useless.

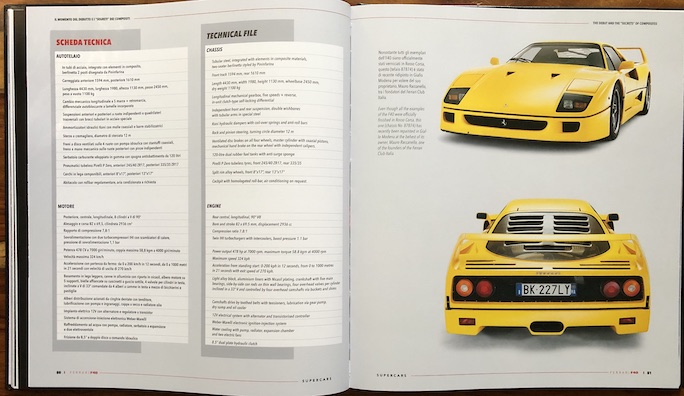

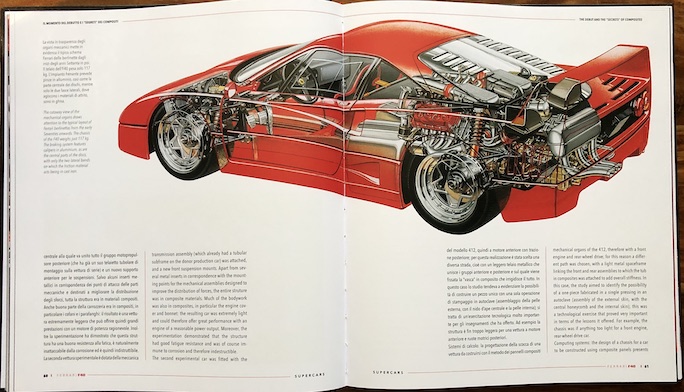

Naturally, flowery and positive language abounds in factory material—everything is formidable, unrivalled—but those excerpts add an important layer to understanding how Ferrari itself saw the car and positioned it in the marketplace. By the same token it is remarkable to see how much technical detail Ferrari disclosed, be it the attributes of “structural adhesives” (for bonding of body panels, a key innovation on the F40) or a discussion of “polynomal camshaft profiles” or the math behind the “Alpha-N principle” that governs fuel injection.

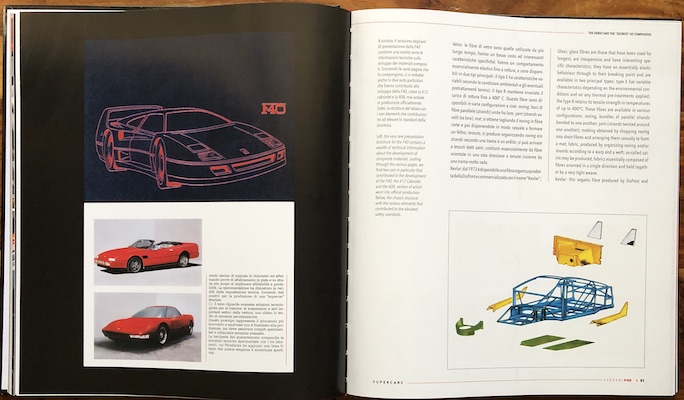

The page on the left is from the “very rare presentation brochure.” It’s interesting that the factory would use two models (the 412 cabriolet and the 408) that never went into production to make a point.

This abundance of source material has one, surely unintended, downside which is that it is not easy to tell apart from Derosa’s commentary. Both are printed in the same font/typestyle so it is only the presence of opening and, more importantly, closing quotes (which this reviewer is certain are missing at times), or grammatical structures such as “we” vs. “they” that clues the reader in whose material he is looking at. This is exacerbated by the fact that the text is bilingual and printed side by side which means any one thing takes paragraphs if not pages to unfold so if your attention wanders you may have to go back pages to re-thread the needle; likewise, just picking a page to read at random will result in frustration.

Several pages are devoted to showing the differences between the prototypes and the production models.

Another item that distinguishes the book is two chapters showcasing two key players in the F40 story, Nicola Materazzi (who died just before the book came out) and Leonardo Fioravanti. Also, an entire chapter is given to recapping in great detail the exuberantly sympathetic road test from Quattroruote magazine (to which Derosa is a contributor nowadays) in 1989. That would turn out to be the halfway point in F40 production and the magazine makes the amusing remark that for the ca. 1000 cars then built there had been 4000 reservations, rendering the car’s MSRP of 374 million Lire “entirely theoretical” because even though the company “had selected with care and diplomacy the names of purchasers from among the restricted circle of VIPs with long-term links to Ferrari,” out-of-control bidding wars and car-flipping were rampant.

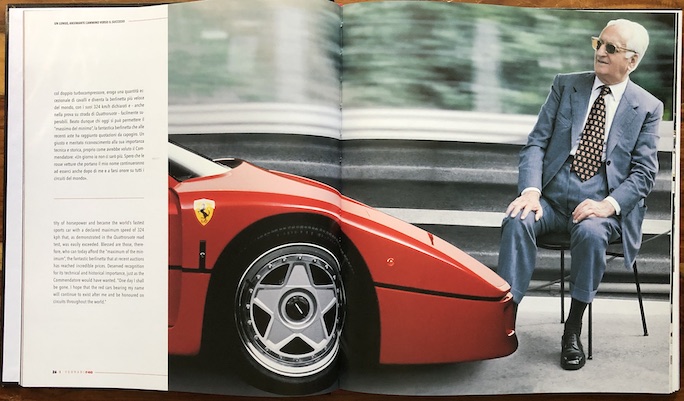

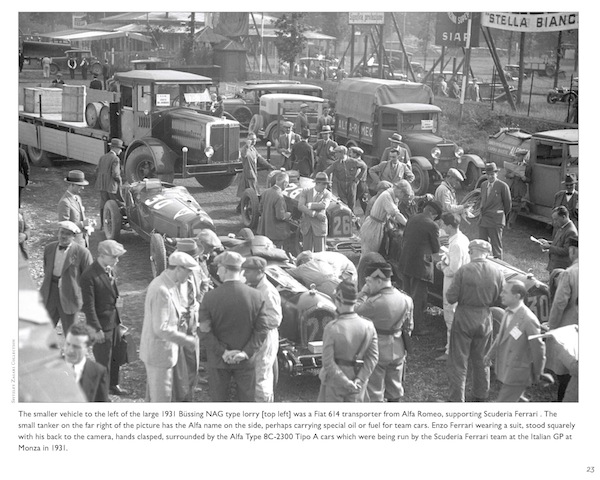

A photo that tells such a big story. You will want to read a proper biography of Enzo Ferrari to grasp what this car at this stage of his life meant to him. He couldn’t have known that he only had a year left. “One day I shall be gone. I hope that the red cars bearing my name will continue to exist after me and be honoured on circuits throughout the world.” What enormous satisfaction it would have given him to see his red cars delivering a stunningly memorable victory at the Centenary race of the 24 Hours of Le Mans in 2023 after a 50-year absence.

(Photography geeks: how did only the top part of the background get blurry? Discuss.)

This book is the second in this publishers new “Supercars” series which means its MO is circumscribed by parameters different from those the author of a stand-alone book has (no tables, charts etc.; also no Index). Still, Derosa is able to introduce relevant context, specifically F40 ancestry in the form of the 250 of the 1960s and then the 288 GTO of 1984 and especially the GTO Evoluzione of 1986 which to the uninitiated pretty much already looks like an F40. Enzo’s start in the business is briefly sketched but nothing so much as hints at his later-day chafing under the meddlesome FIAT influence which is surely the root for the urgency with which he developed the F40 which would turn out to be the final model with his direct involvement. A closing chapter deals with F40 motorsports, both in terms of technical spec and results. Speaking of spec, US-market differences are not part of the picture.

In its day, the F40 was called “the maximum of the minimum” and that was not meant as a compliment. This book is in its way a sort of “minimum” but everything in it is relevant and useful, and it’s nicely made and well illustrated (and the photos are mostly different from the ones in Bluemel’s book). Plus, you can file away some Italian, just in case una delle auto rosse di Enzo è nel tuo futuro. (And, just a friendly jibe, Giorgio Nada’s long-time translator Neil Davenport could probably use his own translator because sentences like “the interior design privileged maxim functionality” or “you will then be projected with a violence guaranteed by the 400 horses” just don’t sound natural. Does he mean “favored” and “propelled”?)

Copyright 2023, Sabu Advani (Speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter