Schlegelmilch Sportscar Racing 1962–1973

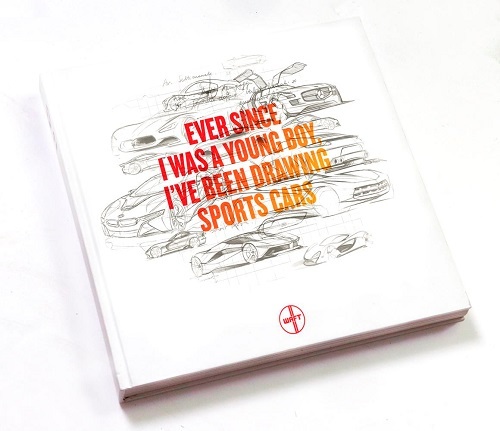

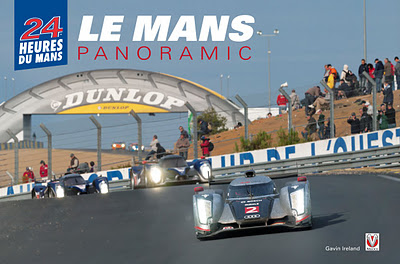

Things aren’t what they used to be, at least not in the world of sports car and GT racing. Whilst the degree of technical innovation we now see at Le Mans humbles F1’s efforts, the modern sports prototype has looks only a mother could love and often possesses a soundtrack that is more muzak than music. Diesel racers are undoubtedly tours de force but the romantic in me is thinking there’s maybe too much technik and not enough passione. Many of us miss the glory days of Group C and some of us also think that the real halcyon period was in the 1960s and early ‘70s. Which, not coincidentally at all, is the era covered by this book.

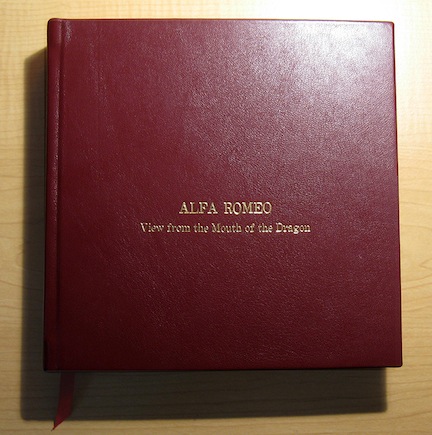

Rainer Schlegelmilch is one of the best motorsports photographers in the world and, quite simply, this book is nothing short of sensational.

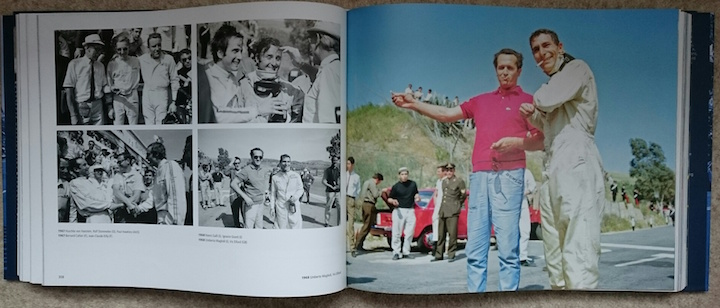

Words, not pictures, are normally what matter most to me but the images in this book are compelling, insightful, and almost lyrical in their depiction of a forgotten age. This is a massive work, coffee table size, and its 540 pages weigh no less than 6 lb. Whilst there are some brief, but informative notes by renowned UK journalist David Tremayne, nearly every page contains the most extraordinary images of the men, the machines, and the amazing circuits of the era. And the pictures aren’t the usual clichéd, tight focussed images of race leaders but a far more wide-ranging look at what now seems a lost world.

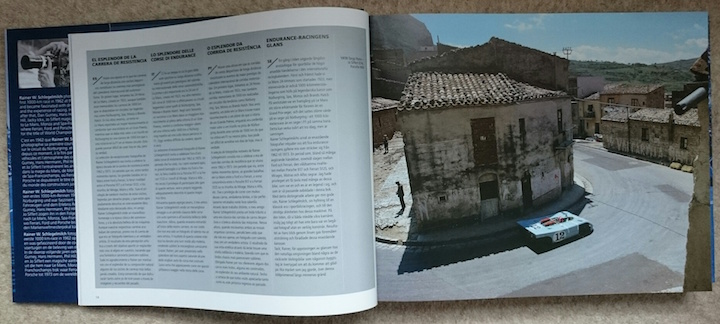

No decade of racing ever witnessed more progress nor produced so many stunning looking machines as the period covered in this book. Machines such as the Ferrari 512 and Porsche 917, both produced to exploit a loophole in the FIA regulations. They were powered by charismatic 12-cylinder engines, the Ferrari (predictably) by a V12 and the Porsche (equally predictably) by an air-cooled Flat 12. The early versions of the 917 had aerodynamics that were wayward in the extreme and drivers counted themselves lucky if they got away with just having been scared senseless; remember, the 917 could pull nearly 400 km/hr down the pre-chicane-era Mulsanne straight. The Maranello machines were never as successful as their Stuttgart rivals but their looks were sublime and in this respect the 512 was almost the equal of the legendary P4, also extensively featured in the book. And what about the amazing Chaparral? Designed by Texan Jim Hall with Chevrolet V8 power, automatic transmission, and a wing the size of a barn door mounted high above the engine cover. God knows what the Sicilian farmers made of the all-white monster of a car as it bellowed around the Targa Florio in 1967!

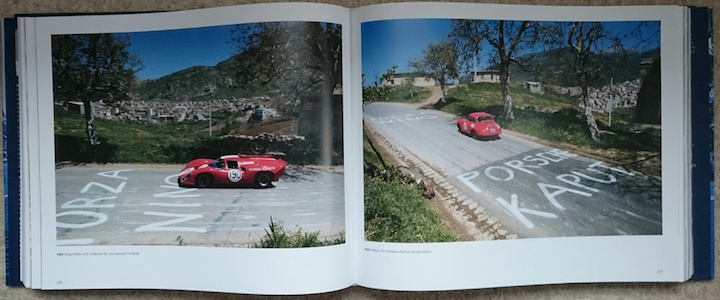

Oh yes, the Targa, the one motor race above all which I wish I had seen in period. Here was a circuit just 45 miles in length, made up of public roads snaking through the villages, olive groves, and mountains of Sicily. Here were Le Mans specification cars (and, in the case of the gorgeous Ferrari 312P, a two-seater Grand Prix car) sliding around town squares and laying rubber outside the pavement cafes. Schlegelmilch’s pictures are a visual feast, none more so than the shot of the Porsche 356 racing along the narrow road between two hand-painted slogans on the rutted tarmac—“Porsche Kaput” and “Forza Nino” (below). Who he? Nino Vaccarella was a local schoolteacher who moonlighted as a works Ferrari driver and who looked as cool as only an Italian racing driver can.

Pedro Rodriguez was another Ferrari driver, if perhaps more renowned for his signature performances in the 917, but in 1969 he drove a Ferrari 312P. The image of this red sports racer, all four wheels airborne at the Nürburgring is startling. Trees shade the track and the crowd is just feet away, “protected” by a wooden paling fence—just how good must that car have sounded as it howled into the distance?

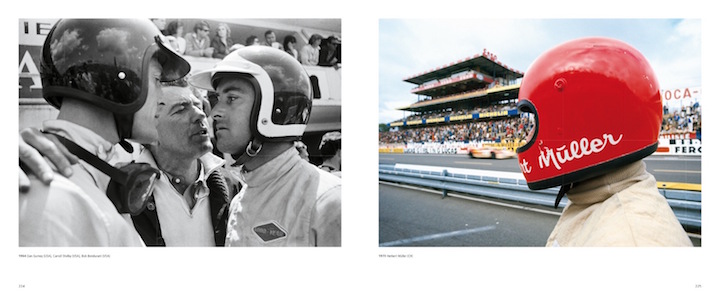

The images of the drivers are as compelling as they are chilling because so few of them were to reach middle age. Rodriguez, his kid brother Ricardo, Jo Siffert, Ludovico Scarfiotti, Rolf Stommelen, Jo Bonnier, Piers Courage, Ignazio Giunti, Paul Hawkins, Lorenzo Bandini—the list is near endless. And yet Schlegelmilch’s pictures bestow on them a dignity that perpetuates their legend. Here is Jo Siffert, cool as can be in aviator shades, and there is Pedro again, in his trademark deerstalker and tweed jacket but with the demeanor of a man who has tamed a 917—in the wet.

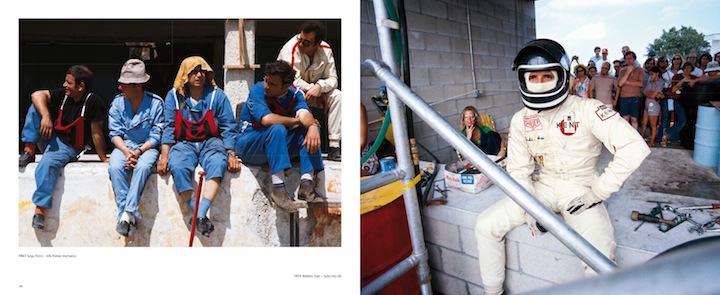

Yet the driver image that makes the deepest impression on me is of a survivor, Vic Elford. He is the near-forgotten Londoner who had talent to give away. He started his 1968 season by winning the Monte Carlo Rally in a 91; a week later, a mere week!, he drove his Porsche 907 sports prototype to victory at the Daytona 24 Hours. Later that spring he won the Targa Florio, having made up a deficit of 18 minutes behind the leaders. Oh, and then he raced in his first Grand Prix, the French, and finished fourth in his Cooper BRM. Quick Vic was some mensch and the pictures of him are remarkable; I have never seen anybody with a thousand yard stare like his. Open face helmet, Nomex mask over mouth and nose, and those eyes. Their intensity is almost frightening.

As always in old photographs there is much unwitting testimony; something that wasn’t important then but leaps off the page now. Like watching a driver (Elford again) drawing luxuriantly on a post-race Gitanes, in the pits, obviously. Or the group portrait of the Gulf Porsche mechanics in 1971; the very high sideburn content makes the first impression but now look at the toolbox: in 2016 there would be a laptop and some surgical grade instruments but back then there was a battered metal toolbox, complete with Siffert’s helmet lying amongst the spanners and pliers. The box is covered in stickers, not team-branded ones though, but instead there are two Ferrari stickers and a Yardley BRM one. Can you imagine Red Bull Racing boss Christian Horner’s laptop sporting a Prancing Horse and a Force India sticker? No, me neither.

A final image to whet your appetite; we all love the Ferrari 250 GTO, right? And we know too that, to be able to afford one in 2016, you need either to be a dotcom billionaire or a Russian oligarch. However, in 1963 you just needed a spare $18,000 to buy one which is the equivalent of a paltry $140,000 at 2015 prices—911 Turbo money. The book has a lovely picture of a GTO at the Nürburgring 1000 km and to say the car is well patinated is an understatement; it is dirty, dented and battered and the Prancing Horse on its flanks looks as though it had been painted on by a nine-year-old. I bet that car now only sees daylight when it is wheeled reverently on to the lawn at the Pebble Beach concours d’elegance; it may be polished to perfection but I know that if it had a soul it would remember its glory days when it howled down the long straight at Reims under a champagne sun.

Just buy this book. It will cost you far, far less than you might think. Last year I read a review of the definitive (and I suspect only) history of the Aston Martin DBR9; that book is 300 pages and costs a cool $450. Sportscar Racing has 540 pages and in the UK costs the equivalent of $45. I mention the UK list price as the book seems to be available in the US only through private sources or international booksellers.

Copyright 2016, John Aston (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter