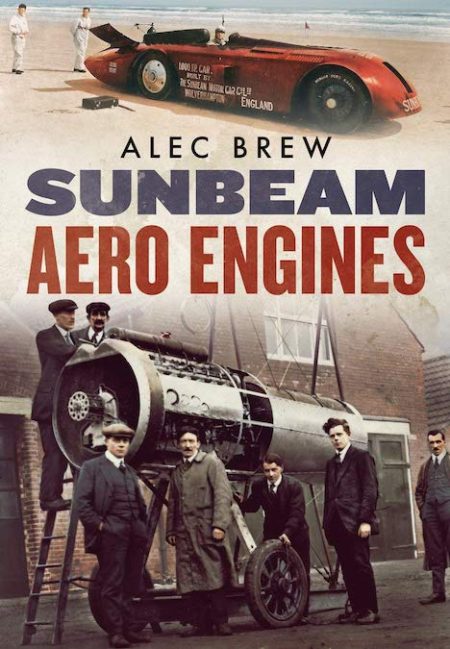

Sunbeam Aero Engines

by Alec Brew

by Alec Brew

“As a postscript to the story of the Sunbeam engines supplied to Russia, in 1990, Peugeot-Talbot, the then owner of the Sunbeam name, received a cheque for £4,816 from the Foreign Compensation Commission USSR (Tsarist assets) Fund as an interim payment towards the invoice of the Sunbeam Motor Car Co., for £16,054, dated 29 November 1918. The invoice was for a licence for aero engines as well as wages and travelling expenses for an engineer who had spent fifteen months in Vinnitsa in the Ukraine. The event is amazing on so many levels, not least the optimism of Sunbeam, just eighteen days after the war had ended, in sending the invoice to the Communist regime.”

The reason for starting this review with an excerpt pertaining to a rather peripheral matter is to illustrate that this unassuming-looking book manages to cast a wide net despite its smallish size and length. It packs a punch—in fact, after reading the first half dozen pages you may well feel like having gotten punched because 200 years of British industrial history are wrung out bam-bam-bam. Unless you are already steeped in this topic you’ll be reading those pages more than once just to sort out the mass of companies, people, and products that lead to—Sunbeamland. Yup, that really was the name of the factory.

Considering how important Sunbeam engines were, not just in the context of WWI aviation, it is odd that the literature is so thin. The only serious non-car Sunbeam monograph of note is the author’s own, from 1998, with the same title and published by Airlife (ISBN 978-1840370232). This new version by Fonthill Media makes no reference to it so it’s not clear to which version the remark that the book is the result of over 30 years of research in the company’s archives applies.

Considering how important Sunbeam engines were, not just in the context of WWI aviation, it is odd that the literature is so thin. The only serious non-car Sunbeam monograph of note is the author’s own, from 1998, with the same title and published by Airlife (ISBN 978-1840370232). This new version by Fonthill Media makes no reference to it so it’s not clear to which version the remark that the book is the result of over 30 years of research in the company’s archives applies.

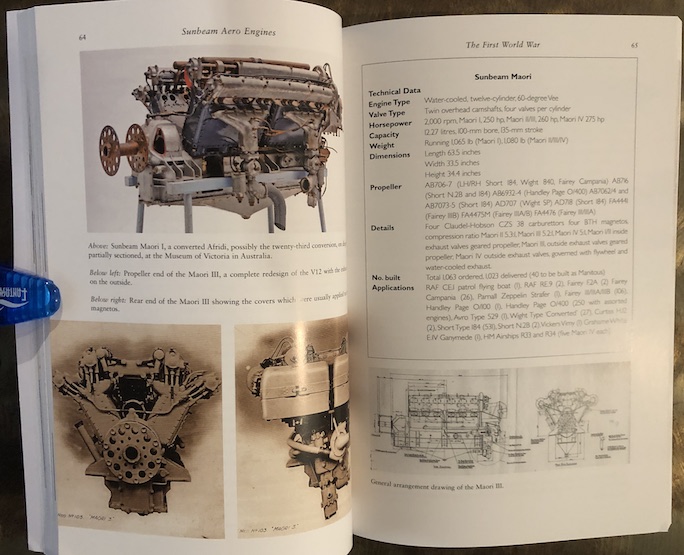

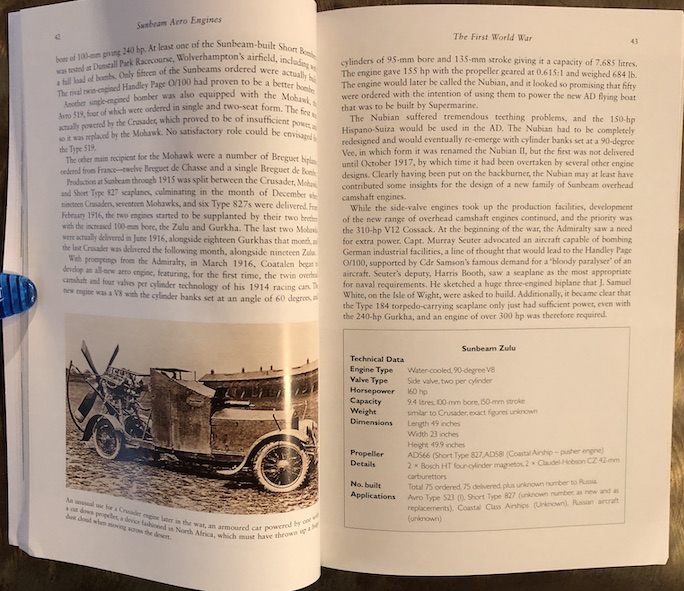

Aviation author Alec Brew certainly has plied his trade for a long time, with over thirty titles published, and is also the founder of the Boulton Paul Association. He knows his subject and he knows the English language, meaning this book is as “digestible” as one could expect of a fact-laden book that has little space to spare for prose. Let your attention wander and you’ll miss something that, absent an Index, you’ll have the hardest time retracing later. Very convenient, on the other hand, is that the tables of technical data that dot the narrative list an engine’s applications i.e. on what machines it was used. On the illustration side too the book goes deep because many have not been published before.

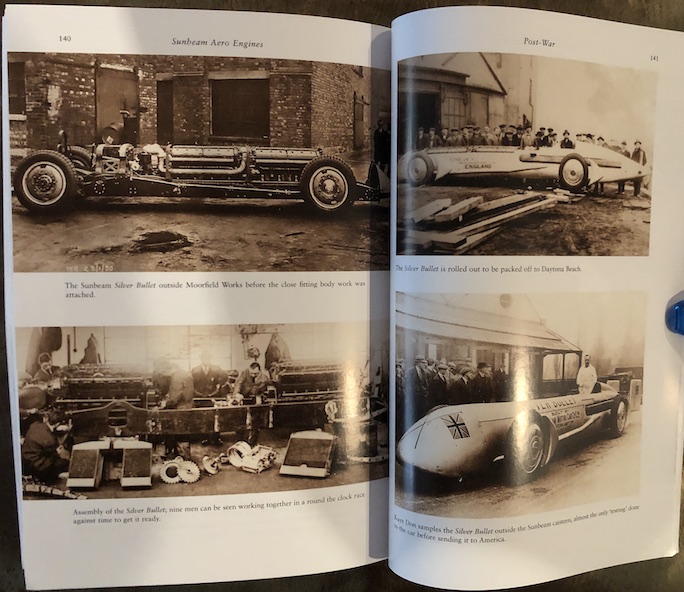

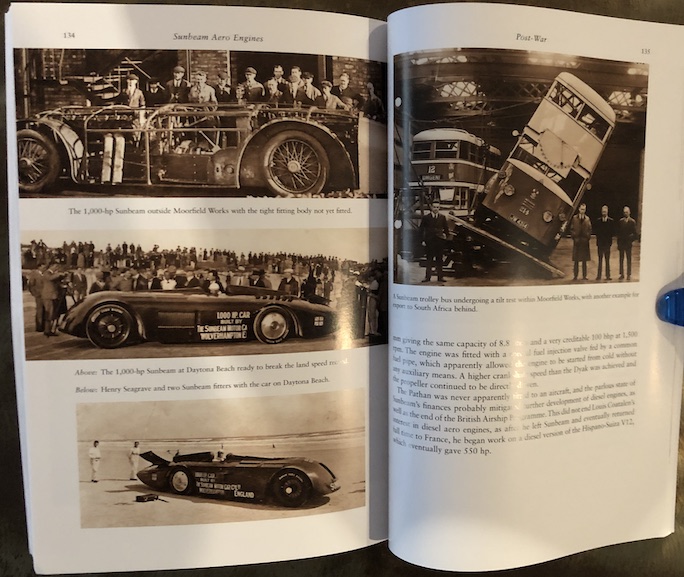

Even that bus on the recto page is a Sunbeam. Will it tip over? Will it? Will it?

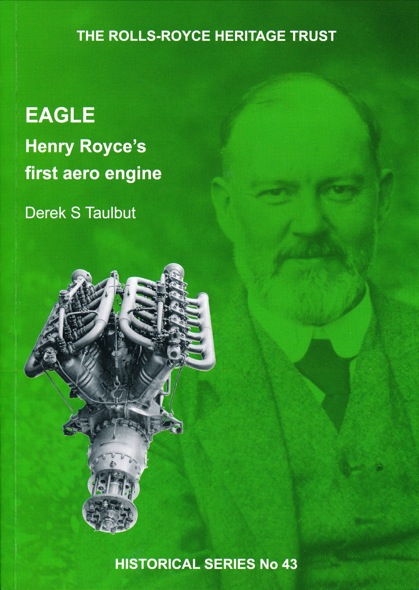

Even experts will find that there is so, so much crammed into this book that unless you have superhuman memory, when you turn the last page you might as well go right back to the beginning and start over. Aircraft, cars, boats, airships, tanks, any number of countries and makers and personalities . . . apprehending the full picture will require serious effort. Consider, for instance, that Sunbeam created 24 quite distinct engines (the colorful “tribal” names help in remembering them: cf. Afridi and Bedouin, or Gurkha, Nubian and Saracen) during the same period that Rolls-Royce did four—which is not to imply that one approach is qualitatively better than another but that Sunbean’s chief engineers and boards followed an engineering philosophy that specifically suited the firm’s structure and capacity.

Museum photos, period photos, general arrangement drawings, specs—this book has everything you’d want.

The prop at the rear is cut down but it’s still a big aircraft propeller.

It is odd to think that on the one hand the Royal Aircraft Factory had praised the Sunbeam’s Crusader as “the first modern British aero engine” while on the other hand the government at the same time ignored this assessment and continued to favor the French engines they considered superior. In that regard, a remark by Louis Coatalen quoted early on is especially poignant: “We had thought of giving up the manufacture of aero-motors altogether, and were just about to drop it when the War broke out.”

Not a casual read, which, really, is a compliment. (As an aside, note the $/£ prices; if this book were published today [2023] they’d be much farther apart.)

Copyright 2023, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter