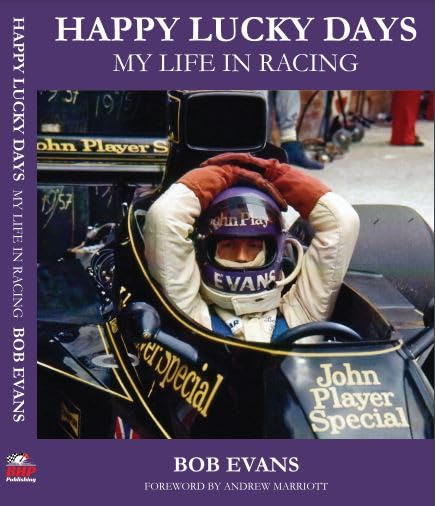

Happy Lucky Days – My Life in Racing

by Bob Evans

by Bob Evans

“Look mate, if it’s a FF (Formula Ford 1600) car it needs a half inch anti-roll bar, a F3 car needs a three quarter inch bar, and anything with a bigger engine you need a one inch bar front and back.”

—Palliser designer Len Wimhurst’s 1970 anti-roll bar* mantra.

Formula One is no longer the apex of motorsport, and hasn’t been for many years. It has become a sport in its own right, and some of F1’s zealous new fanbase seems to revel in its ignorance of other disciplines. I had recent proof of this in an online discussion about the merits of a retired British driver. He had enjoyed a successful career in single seaters and sports cars on both sides of the Atlantic in the 1970s and ‘80s. But because the driver had enjoyed very limited success in Formula One, my Internet friend regarded him as little more than a weekend warrior compared to the demigods who occupy even the back of the current F1 grid.

My friend would probably have dismissed Bob Evans’ career too—after all, he only competed in a dozen Grands Prix and never scored a single point. But back in the days when “podium” was a noun, not a verb, Evans belonged to that cohort of very capable British drivers who either never got a Formula One drive or, if they did, their opportunity came at the wrong time or with the wrong team. The list of drivers is a long one, and Evans (b. 1947) joins names like Tony Trimmer, Ian Ashley, Geoff Lees, and Jim Crawford in having once touched the hem of Formula One but who are now almost forgotten. Except by the hardcore enthusiasts who are the target audience for this very readable book by Bob Evans.

This is an entertaining autobiography by a driver who followed the well-trodden path from the hotly contested junior formulae up to the big power of Formula 5000.** The late Sixties and early Seventies now seem a golden era, albeit a dangerous one from the perspective of 2024, where the risk of a driver being injured or killed is small. Evans’ story is told largely as a linear narrative, beginning in 1967 at Brands Hatch in an orange Austin Healey Sprite and ending almost twenty years later. There was a lot of racing in between, from success in F5000, frustration in Formula One and then a final act in sports prototypes, notably Dome and Aston Martin Nimrod.

Anybody who spent much time at British race circuits in the Seventies will smile involuntarily at the photographs of ramshackle paddocks, oily-overalled mechanics, and basket-case tow cars. The quality of the photographs is wonderfully varied, a delightful contrast to the pin-sharp uniformity of their modern counterparts. And if some of the images are fuzzy and un-staged, that only adds to their charm. They were taken in the moment, because how could the photographer have suspected there would be a new audience for them, half a century later? They speak of an informal world, where drivers lived in and for the moment, as yet unaware of “brand image” and the rest of the corporate nonsense that taints modern motorsport. TV documentaries on Seventies’ Britain revel in portraying a down-at-heel country, beset by strikes and inflation, but they don’t mention how much fun Bob Evans’ generation was having. Gone were the posh drivers and stifling formality of early Sixties’ motor racing, let alone that of earlier decades. Dress was casual, sideburns extravagant, and girlfriends looked more like pop stars than debutantes. This book reminds the reader that the era it describes was a bloody marvelous time in which to enjoy motor racing.

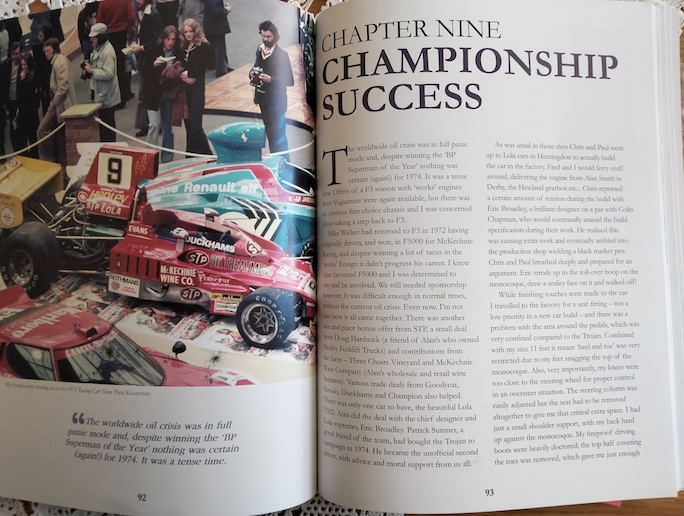

I assume that most of the book’s early content comes from diary extracts, and the result is often little more than race by race summaries. It is a familiar trap into which some driver biographies fall, with the story of one season’s slings and arrows following another. But while there is a taste of this here, the book is redeemed by more personal recollections of the people who punctuated the author’s story. Men like Alan McKechnie, the wheelchair-bound bon viveur, race team owner and vintner, who supported Evans for much of his career. Endearingly, he is described as the man “who would spend £20 entertaining someone to sell them a £10 case of apples.

It’s relatively unusual, and thus refreshing, to hear of a driver’s personal and cultural hinterland, and Bob Evans talks fondly of his wife Annie bringing their infant son Tom to race meetings, despite this being frowned upon in that more sexist era. And anyone who knows his Little Feat from his Miles Davis is someone with whom I’d happily share a bottle of Shiraz.

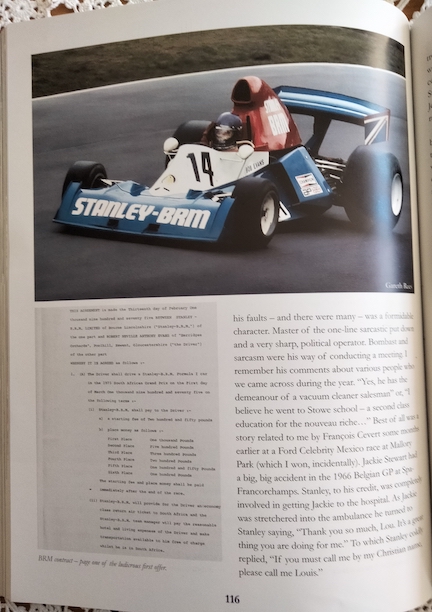

Evans starred in F5000 but not Formula 1, and yet his memories of his period with the then hopeless BRM team are a highlight. The bluster and pomposity of the preposterous Louis Stanley have already illuminated many an F1 biography but Evans’ “Big Lou” stories still entertain. The author’s wife Annie crisply dismissed “Lord” Stanley as “. . . the most unpleasant, vulgar man I have ever met. I never knew anyone who didn’t secretly hate or despise him.” BRM’s engine guru barely escapes alive either: “. . . the odious, bumptious and appalling Aubrey Woods.” Ouch.

Things didn’t get much better at Lotus, which in 1976 was enjoying one of its periodic slumps, this time between the waning of the 72 and the waxing of the ground effect 78 and 79. Evans was aware that he was only a stop-gap driver before prodigal son Andretti returned, but as legendary manager/promoter/fixer Nick Brittan had put it, “Besides, who refuses a drive with Team Lotus, whatever the circumstances?” Evans didn’t and concluded, as he left the team, “Maybe I was lucky, I lived to tell the tale.” Which is more than can be said of some of his predecessors with the Norfolk team.

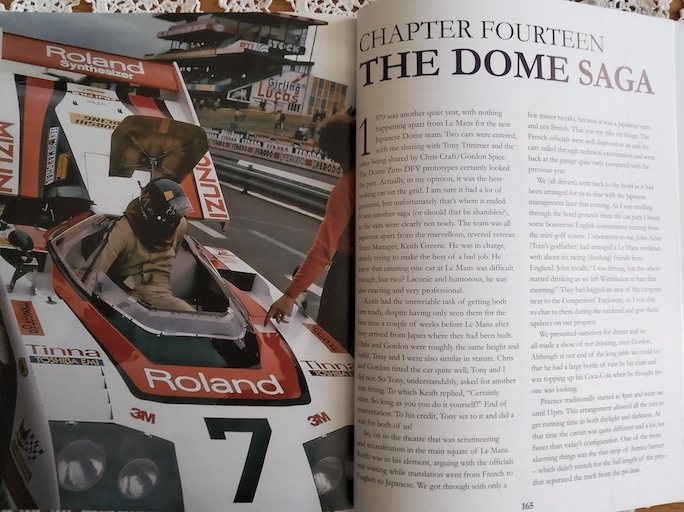

Just as fading rock groups discovered that it was possible, and often very lucrative, to become Big in Japan, so did Bob Evans, who enjoyed an Indian Summer with Dome. His account of dealing with the process-heavy Japanese style of working is amusing and insightful but avoids the common trope of patronizing and mocking such a different culture. He obviously loved his time in Japan, unlike his swan song with the Aston Martin Nimrod team whose wildly ambitious plans were both unfounded in reality and unmanifested in results. The more experienced the author became, the less restrained he became in his criticism of badly run teams. Primed by his demolition of the bad joke BRM had become, he is deliciously scathing about the Nimrod project. Aston boss Victor Gauntlett’s name might have hinted at nominative determinism but he was “totally unrealistic” in believing a Le Mans victory might once again fall to Aston Martin. As for Robin Hamilton, Gauntlett’s co-conspirator, I’d guess he and Bob Evans were not on each other’s Christmas card list. Seasonal cheer is going to be in short supply after your driver dismisses you as “pompous, aggressive and pontificating on any aspect of racing that he had clearly no experience of whatsoever.”

The book’s conclusion is abrupt. In the postscript the author admits that he “made some bad life choices in my racing and private life in the late eighties, but I had to live with them.” Without wishing to be prurient, I’d like to have known more, not least because the book had already revealed its author to be an intelligent and thoughtful man, one who had clearly enjoyed navigating through motor racing’s then dangerous terrain. But that is only a quibble, because this is a book I can recommend. At its best it reminds me of long-ago sunlit afternoons, when I’d watch the thunderous train of F5000 cars, and spot Evans’ trademark purple crash helmet in the cockpit of his red and yellow Lola T332.

- *often termed “sway” or “anti sway” bar in the US

- **Formula A was the original name of F5000 in the US

Copyright John Aston, 2024 (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter