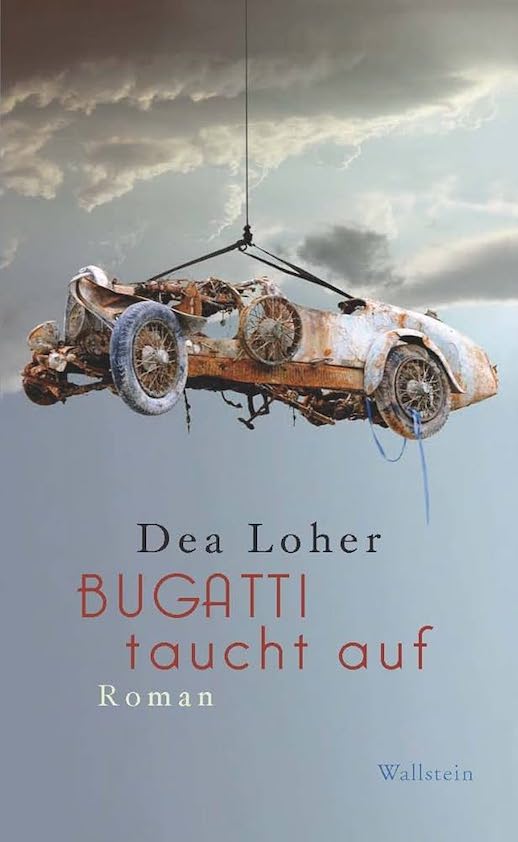

Bugatti taucht auf

by Dea Loher

by Dea Loher

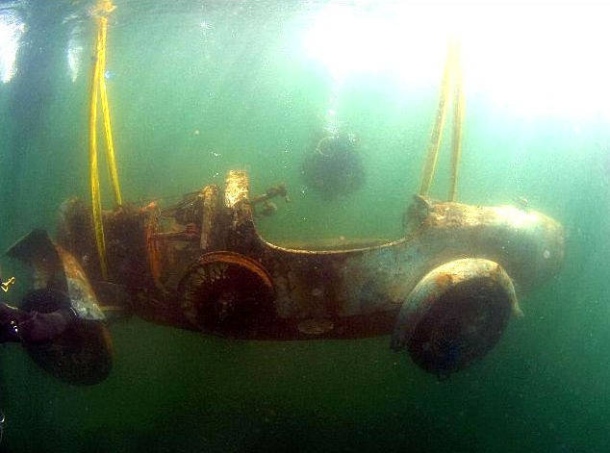

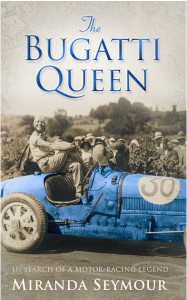

(German) Bugatti people will see the cover and perk up. Could this be a book about chassis 2461 that was raised with much fanfare from its watery grave after 73 years? Yes, but mostly no. It is that car, the 1925 Type 22 Brescia that was hidden by its third owner from the tax authorities by suspending it from a float on Italy’s Lago Maggiore. The chain that tethered it to the float (it is still not clear how that was ever supposed to work) rusted through and the car plunged 150 feet to the lake bottom where it lay abandoned until a local diving club extracted it in 2009, then donated the rusted hulk to a charity that enlisted Bonhams to sell it at auction. US collector Peter Mullin bought it and 2461 is now on display in his museum and will remain unrestored, its decay having been arrested or retarded by a costly preservation effort.

So much for the easy part.

The reason it had to be that car and no other is that the place 2461 occupies in this novel is on the one hand based on facts that make its history relevant to the other parts of the story but on the other, metaphorical. The title already hints at this; taucht auf in German means specifically “surfaces” and generally “appears.” The car literally surfaces from the bottom of the lake and figuratively surfaces in the lives of people. It is one of the two legs the story stands on, the other, also based in reality, a brutal, random, senseless murder.

Winner of many important awards, German playwright Dea Loher (b. 1964) is among that country’s most-performed dramatists. No matter that in an interview she once insisted “I am entirely unable to make anything up,” since 1991 she has written 17 plays that have been performed over 300 times and translated into 30 languages. Guilt, sorrow, redemption, complex people, and intricate relationships are recurring themes. All of these permeate this her debut novel, only her second work of prose—which is actually her first love and predates her theater work. This is Literature with a capital “L,” an impressive example of meticulous writing and word craft. The language is dense, atmospheric, full of nuance, pregnant with both emotion and open-endedness, the latter—as all meaningful literature—leaving space for the reader’s own mind and soul and experience to color his reading. A book, then, that on each re-read will resonate a little differently; a book you won’t outgrow; a book you’re not ever “done” with.

Winner of many important awards, German playwright Dea Loher (b. 1964) is among that country’s most-performed dramatists. No matter that in an interview she once insisted “I am entirely unable to make anything up,” since 1991 she has written 17 plays that have been performed over 300 times and translated into 30 languages. Guilt, sorrow, redemption, complex people, and intricate relationships are recurring themes. All of these permeate this her debut novel, only her second work of prose—which is actually her first love and predates her theater work. This is Literature with a capital “L,” an impressive example of meticulous writing and word craft. The language is dense, atmospheric, full of nuance, pregnant with both emotion and open-endedness, the latter—as all meaningful literature—leaving space for the reader’s own mind and soul and experience to color his reading. A book, then, that on each re-read will resonate a little differently; a book you won’t outgrow; a book you’re not ever “done” with.

Two seemingly disparate strands are developed, one at a time. Only in hindsight does their connection become apparent. The book opens on Ettore Bugatti’s (the car maker) younger brother, Rembrandt, the sculptor. The story he tells in the form of 1914–16 diary entries is fictitious but informed by actual events (the war, his brother, his depression, his art). While Loher takes artistic license with her characters and the story arc, she has obviously done her research. It is easy enough to portray Rembrandt as a sculptor of animals—he was—but she also gets details right such as his striving to finish his roughs in one single day, a peculiarity in which he did indulge. Loher’s attention to this sort of detail is something you’ll want to bear in mind lest you blame her for getting, for instance, the 2461 ownership history all “wrong” (here it is an ex- René Dreyfus car with racing history, something that practically every other review mindlessly parrots). Rembrandt’s account ends with his suicide: “I shall lay down on my bed, on my back. I shall clasp my hands on top of my stomach. I can’t be sure I’ll be able to lie still.”

Part 2 relates the gut-wrenching story of the real-life 2008 murder in a lakeside town of a 23-year-old man who happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time. Each part is written in a distinctly different voice, Rembrandt’s wistful and ruminating and in the first person; the story of murdered Luca Mezzanotte (i.e. Damiano Tamagni who was beaten to death by thugs during carnival) as eyewitness accounts and as shockingly dispassionate as a police report. The more we are told the less we know as to what really happened and why. Peripheral note is made that Luca is an amateur diver who knows that fellow divers claim to have seen the wheel of an old car sticking out of the mud on the lake bottom but he dismissed it as a tall tale.

Part 2 transitions into part 3, the largest in the book, with Luca’s devastated family wanting to erect a memorial. A distant cousin, Jordi, who is a more serious, semi-professional diver, hits upon the idea of finding and raising the Bugatti and then sell it to raise funds. The dive itself is a nail-biter, and, as everything else in this novel, a metaphor for life itself.

So, to return to the beginning: this is the story of that car, but it is not what the story is about. It is, rather, a story about nothing less than the meaning of life, of countering a bad deed—murder—with a good deed—bringing the car to the surface

So, to return to the beginning: this is the story of that car, but it is not what the story is about. It is, rather, a story about nothing less than the meaning of life, of countering a bad deed—murder—with a good deed—bringing the car to the surface

These are the novel’s basic building blocks. Its fabric cannot be meaningfully related here and needs to be discovered by each reader. Much like Loher’s theater plays, it is a collage rather than a linear story. It is not an easy one, certainly not convenient or pretty. It will weigh on you. Lots of people suffer, not all dots connect, many things mirror many other things, in obvious and not so obvious ways. You won’t discover them all at once.

If this book ever does get translated one wonders how a translator will be able to capture the fullness of Loher’s so very specific way of painting with words.

Copyright 2012, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter