The State of American Hot Rodding

Interviews on the Craft and the Road Ahead

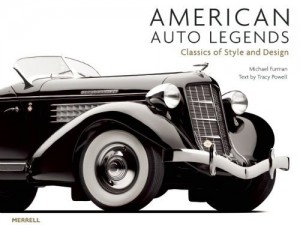

It’s a familiar gearhead story. A car guy accidentally comes across an automotive find in an out-of-the-way spot. He arranges for its transport home, then spends the next few years of his life shaping it into something he can call his own. Once the vehicle is completed to his satisfaction, he tests it by taking it out—to a car show, a cruise, or perhaps on a hot rod tour.

However, when car guy David Lawrence Miller decided to crisscross America in his custom 1958 Chevy Apache pickup, he did so not only as a gearhead but also as a research scholar. The resulting book represents one man’s quest to uncover the origins of the hot rod phenomenon, to contemplate its current condition, and to determine the necessary steps for its continuation into the future. As he set out on his cross-country adventure, Miller sought to explore, examine, and appraise the past and future of hot-rod culture through the life experiences of its most famous and infamous members. As an individual invested in the practice of hot rodding, Miller also understood the importance of recording the stories of those whose time remaining in the hobby is limited at best. The book, therefore, is not only an investigation into the current and future state of hot rodding, but also serves as an homage to the legendary figures of American hot-rodding culture.

Miller’s book has a simple construction. He begins with an explanation of hot rodding for the uninitiated, establishes his own credentials through a brief chronology of his involvement in the culture, provides a detailed description of his own build, and as a geographer and scholar, presents his research methods. In this first section, Miller is concerned with legitimacy—that of himself as a gearhead and that of hot rodding as a pastime worth preserving. Although Miller acknowledges the environmental costs associated with the hobby, he also recognizes and appreciates hot rodding’s status as a “revolt against the commonplace.” While hardcore hot-rodders will have little argument with Miller’s assessment, those without a gearhead gene may need additional convincing.

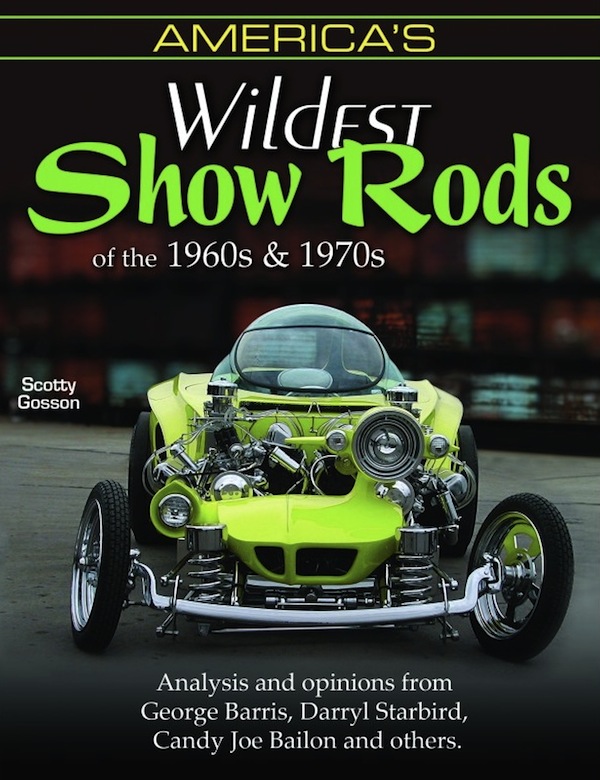

The large middle section of the book is devoted to interviews with 16 hot rod legends of various persuasions. The impressive list includes designers, builders, and restorers of pure hot rods, 1950s customs, as well as rockabilly and futuristic vehicles. The conversations are, for the most part, unedited. Although Miller set out with a list of discussion topics, the interviewees often meandered into tangential but nonetheless fascinating, recollections. Hot rod enthusiasts will recognize many of the individuals Miller engages, and will no doubt enjoy trips down memory lane with people like Bobby Alloway, Bo Huff, Darryl Starbird, and the inimitable Gene Winfield.

While Miller’s intent was—as the title suggests—to inquire about the current and future state of hot rodding, the stories included in this collection are overwhelmingly focused on the past. These are old car guys after all; consequently most chose to talk about their beginnings in the hobby, their successes as builders and designers, and memorable cars on their résumés.

Aficionados will enjoy reading about Darryl Starbird’s first bubble top car, Bo Huff’s collection of “works of art on wheels,” and the “Ohio Flames” Bobby Alloway made famous. The strength of Miller’s book is as a repository for the oral histories of an impressive collection of aging hot rod pioneers. The car buffs interviewed for this project provide fascinating and illuminating personal histories of American hot rodding in all of its many guises. However, what is lacking in the responses is a convincing antidote to the greying of hot rod culture. While the men collectively agreed that interest in the culture must be passed on to younger generations if it is to survive, they were unable to offer concrete suggestions on how that might be accomplished.

In the last section, Miller reiterates the conditions leading to the culture’s precarious future—rising fuel costs, costs to the environment, and the move toward autonomous vehicles—and contemplates possible solutions. The incorporation of new technology into old cars, Miller argues, provides the greatest opportunity for hot rodding’s survival, as it will not only address environmental issues, but will make the hobby more attractive to younger car buffs. However, neither Miller nor those he interviews suggest that an effective way to increase participation is to make hot rodding more inclusive. As a cultural studies scholar, I must mention that hot rodding culture is now, and has always been, composed of individuals who are overwhelmingly white, male, and heterosexual. Making the hobby accessible to a wider audience has the possibility of bringing new interest, enthusiasm, and ideas to the hobby. Muscle car culture, long a bastion of masculinity, has witnessed an influx of female enthusiasts. The inclusion of women has not only stemmed the tide of attrition, but has changed the face of the culture. In addition, by concentrating primarily on aging car buffs rather than up-and-coming builders and designers, Miller missed an opportunity to consult with those not as deeply rooted in the past who might have better insight into the future.

Miller’s enthusiasm for hot rods and his reverence for hot rod legends are evident on every page of this book. For the hot rod aficionado, this book provides an opportunity to hear from the oldtimers before they pass onto that great drag strip in the sky. For the casual car buff, the book offers a unique glimpse into a specific car culture and introduces the individuals who made a name for themselves within it. As a certifiable gearhead, Miller loves the world of hot rodding; he interviewed men he has long admired in the hope that in their wisdom they would provide the key to the culture’s survival. Only time will tell if, in fact, Miller succeeded.

Copyright 2018, Chris Lezotte (speedreaders.info).

This review appears courtesy of the SAH in whose Journal No. 295 (November / December 2018) it was first printed.

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter