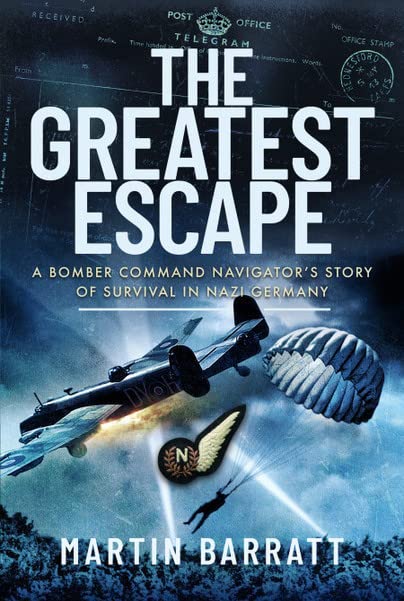

The Greatest Escape

A Bomber Command Navigator’s Story of Survival in Nazi Germany

by Martin Barratt

by Martin Barratt

“We were all shit scared and anyone who says he wasn’t was a bloody liar. But you didn’t dare show it. You didn’t want to let your mates down or let them see it. You couldn’t. We all had a job to do, and we relied on each other.”

—Sergeant Harold Barratt, navigator, Handley Page Halifax JB 869 DY-H, 102 Squadron, Royal Air Force

As part of its wellbeing initiative, the University of Cambridge recently announced that it would offer coloring books and games of hide-and-seek to students. This was to help them cope with the trauma of being a student at one of the world’s best universities. Harold Barratt didn’t benefit from coloring books during his incarceration at Luft VI Heydekrug; the only hide-and-seek he played was after he escaped, and involved the bad guys toting Mauser Kar 98k rifles.

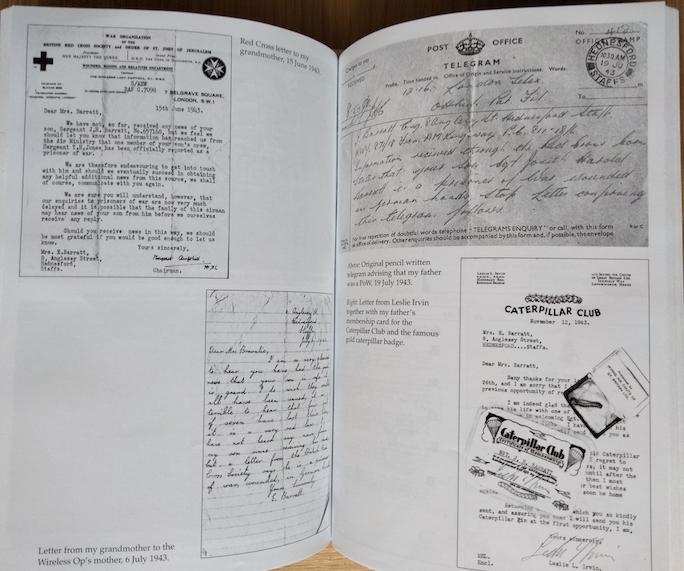

Martin Barratt is Harold’s son and this wonderful and profoundly moving book represents 24 years of research into his father’s life and wartime record. It is as fine a tribute as any son could make, not only to his late father but also to his Bomber Command comrades, so many of whom did not survive to enjoy the freedom for which they fought.

Harold Barratt’s life story was both mundane and extraordinary. He grew up in the industrial heartland of the English West Midlands, the area known as the Black Country because of the soot that covered every building, the product of heavy industry and coal mining.

Having spent my own childhood in a coal mining village, I can only agree with the author’s crisp dismissal of those who romanticize an industry whose reality was “that it was a bleak, dangerous, dirty and ruinous life . . . (which) my grandmother was absolutely determined her only son would not follow.” And nor did he, working aboveground as a payroll clerk and studying engineering. But this was the early 1930s, and the author describes the inexorable slide of the country into another war with Germany, just twenty years after the “war to end all wars.” It’s a concise but finely observed account, and it was appropriate to include the lines from Heinrich Heine, the 19th century German author who famously said “Dort, wo man Buecher verbrennt, verbrennt man am Ende auch Menschen.” (“Where they burn books, they will, in the end, burn human beings too.”)

Harold Barratt was enlisted into the army in March 1940, two months before Dunkirk. After seeing the devastation wrought by the Luftwaffe bombing of Coventry, only a few miles from his home “he became anxious to do something that would allow him to strike back” and he volunteered to serve in RAF Bomber Command.

After training in Canada and Florida, the really dangerous work began on Harold’s return to Britain as a navigator. Even the training, undertaken mainly over friendly territory, took a shocking toll of aircrew, with 5000 (yes, you read right) dying “on training flights, mostly a mix of pilot error and mechanical failure.” Once on active service the odds shortened further and “only U Boat crews suffered higher proportionate losses.”

I live in northeast Yorkshire, where the remains of many WWII bomber bases can still be seen—crumbling Nissen huts, empty control towers overlooking silent wheat fields, a race circuit on what had been RAF Croft and a drag strip at RAF Melbourne, five minutes flight from RAF Pocklington. It was from that aerodrome that Harold Barrett’s Halifax bomber took to the air for the last time on 4 May 1943, en route to the Ruhr Valley. “Gentlemen, your target for tonight is Dortmund.”

Not all the crew survived after H-Harry was shot down over Germany, but Harold did, suffering back and ankle injuries as he landed. It would be nearly two years before he tasted freedom again, having endured almost unbearable brutality and privation as a POW. He came close to being lynched by German civilians enraged by the death and destruction wrought by the Allied bombing campaign, whose personnel were demonized by Hitler’s chief propagandist Joseph Goebbels as Terrorflieger und Luftgaengsters. But, as the title suggests, Harold did manage to escape captivity—twice in fact—thanks to his ingenuity and newly learned German. However, he was recaptured and returned to the ghastly environment of Stalag Luft VI at Heydekrug (in what is now Lithuania) before being transported in hideous conditions to the fresh hell of Groß Tychow (north-western Poland). And it got worse, as the emaciated prisoners were then forced to walk for hundreds of miles as the Allied invasion moved ever eastwards.

This is not an easy book to read. The author rightly doesn’t shrink from describing the savagery and gratuitous cruelty meted out by the German guards, the most depraved of whom no longer possessed even a trace of humanity. Many prisoners died, executed randomly, cut down by disease or simply of malnutrition. Yet somehow Harold survived, his captivity punctuated by writing letters home—every single one beginning and ending with the same simple, yet heart-breaking words, “Dear Mother & Dad and all at home” and ending “Love Harold.”

Harold was liberated from Stalag XI Fallingbostel on 2 May 1945, flown home and, shortly afterwards, was demobbed. After “letting off steam” (and who could have blamed him?) Harold made exactly the sort of life one might have imagined for him before 1939—a wife and family, and a decent career in a country that was to enjoy decades at peace. But the author knew that his father’s physical scars were not the only legacy of Harold’s years in captivity. He was “. . . A complex and often difficult man . . . a mass of contradictions, at times achingly funny, insightful and cultured . . . at other times harsh, cold, distant and often seemingly troubled.” The account of his father’s last Christmas moved me immensely, and yet what a fitting last testament it was for a man who had seen the best and worst of humanity.

In Britain (and possibly elsewhere) we have had a curious and sometimes unsettling relationship with our war dead. Until the last decade of the last century, commemoration was largely confined to Remembrance Sunday in November, marking the 11 November armistice of World War One. Poppies were worn, hymns were sung, and silences were observed. But, latterly, my country’s respect for its fallen has been seasoned with near hysteria as it skated on the thin ice of idolatry. Men like Harold Barratt were elevated from old soldiers (as veterans were called then) to hero status by a population which seemed to positively revel in grief for men who had served their country generations before.

As this book shows us so brilliantly, men like Harold weren’t heroes at all, and to bestow that status upon them is insulting and ill-founded. Because they weren’t the “Greatest Generation” they weren’t superhumans, but they were something both much more laudable and yet totally unremarkable. Men and women like Harold Barratt were ordinary people thrust by events into extraordinary situations. They were people just like us, often scared, confused, traumatized and yet always muddling through, doing their best, doing their duty, no matter what horror they faced nor how long the odds were against them. Churchill said “Cometh the hour, cometh the man,” and Harold Barratt was one of those men, and so was Flt Sgt John Keys, the uncle who bequeathed me my forename, and whose Halifax was shot down over the Somme in 1944.

Copyright John Aston, 2023 (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter