Grand Prix Bugatti

I love Bugatti vehicles. It’s as if everything mechanical on the car is meant to puzzle the viewer. If I owned a Bugatti, I’d have to take it all apart to see how it was designed, manufactured, and assembled!

Basically, that’s what this book does for you. It’s not a mechanic’s manual for 1923–1933 Types 35, 37, 43 or 51 Grand Prix Bugattis, but it gets close. Of the book’s 116 black and white photos, 41 show close-ups of parts of the car. In addition to these photos, there are 25 drawings that show how the various parts were made. For example, an elegant cutaway drawing that covers two pages of the book displays the press-it-together crankshaft for a little Type 35 1991cc straight eight Bugatti engine. Thin, ultra-light, one-piece machined connecting rods, running on narrow roller bearings for minimum friction at 6,000 rpm, are clearly shown, as is a cross-sectional view of the car’s small eight-inch diameter wet clutch. Elsewhere on display in the book are drawings of the brakes, transmission and the rest of the drive train, including the piston, head, valve train, rocker arms, oiling system, blower, differential, frame, aluminum wheels, radiators, body, and dash layouts.

The book opens with two nice drawings of a Grand Prix car, then dives directly into the Table of Contents. After the Contents, a multi-page section lists all the illustrations in the book by chapter and page number. A short Introduction prefaces “Part I: Racing History,” starting with the 1922 French Grand Prix in Strasbourg, which set the stage for the future success of the Bugatti Grand Prix racecars. The loss at the 1923 Indianapolis 500 is described in chapter 2, then the amazing wins by Bugatti in the 1920s against stiff competition from Fiat, Maserati, and Alfa Romeo carry the reader through a total of 13 chapters, ending with the 4.9- and 3.3-liter cars of the early 1930s that failed to fend off the all-powerful German Auto Union and Mercedes challengers.

“Part 2: Design And Construction,” is composed of chapters 14 through 16 titled: “The Engine,” “Transmission,” and “Chassis Construction.” This is the section with the most blueprints and part-specific photos. Following that is Appendix 1, that breaks out technical data on the number of cylinders, bore, stroke, number of valves per cylinder, horsepower, etc., all the way through to the gearbox, rear axles, and brakes for all the cars and their variations. In Appendix 2, Schedule I lists every Type 35, 35A, 35C, 35T, 35TC and 39 Grand Prix car made from November 1924 to September 1931, the car’s original purchaser, its chassis and engine number, and the name of the current owner at the time this book was written in 1968. Schedule II covers the Types 37 and 37A from 1925 to 1931. Schedule III covers the Type 43 sales and delivery data from 1927 to 1935. Schedule IV does the same for the Type 51 manufactured from 1931 to 1936. A five-page dual-column Index ends the book.

Conway, the author of this book, does an excellent job describing both the race history of the Grand Prix Bugatti, as well as the technical history of the cars. Born in 1914, he became an aircraft engineer after graduating from Edinburgh and Cambridge. He eventually worked for Short Bros. as Chief Engineer, then moved though numerous aircraft engine projects including the Olympus engines for the Concorde aircraft, ending his career as a Director of Rolls-Royce and Group Managing Director of Rolls-Royce Gas Turbines. When he retired he became Chairman of the Bugatti Trust and Vice-President of the Bugatti Owners Club. He wrote his first book, Bugatti, in 1963 and then this book, Grand Prix Bugatti, in 1968. His love of Bugattis, and his comprehensive understanding of all things mechanical, combined with his clear, unhurried, yet efficient writing style, make for a book considered a timeless example of really first-class automotive literature. Conway died in 1989.

Uniformly gray photos of these beautifully proportioned racecars deminish the visual impact the book could have had, as does the text which appears to be photographically reproduced from the original, and so lacks the sharp punch the original possessed. But the quality of the writing remains the same. It was a great read in 1968, it’s a great read today, and it will always be a great read. Gearhead Alert: on page 150 there appears to be an original typo from 1968 concerning Type 51 inlet/exhaust timing. The “before bdc” and “after bdc” inlet and exhaust timing data in the chart seems inverted. A minor point, admittedly, but on a book about Bugatti, himself a striver for perfection, pointing that out seems worthwhile.

For me, one of the most amazing things about the Grand Prix Bugatti racecars is that they were frequently simply driven to the race track, then, after the race was over, driven back to the factory, or home if you were a private owner. No trailers or specialized Formula 1 747 transportation jets for Bugattis. Buy a Bugatti, drive it to the track, race it, then drive it back to the hotel for drinks and a celebration. Sounds like fun.

“Upside down and backwards” perhaps best describes Ettore Bugatti’s almost mischievous design philosophy. Things are not as they appear. Where American cars were designed to be easily worked on by Billy Bob behind the barn, the Bugatti was the opposite in concept. Huge amounts of money, time, and attention to detail were expended building them. The end result was magic in mechanical form that only lasted 5,000 miles between expensive rebuilds. Between rebuilds, however, Bugattis were powerful little high-revving cars for the ultra rich that darted like hummingbirds from place to place. They were sprightly, daring, and beautiful, making the other cars of the 1920s and 1930s appear slow and lumbering by comparison.

Zip. Zip. Fading laughter. A Bugatti just passed!

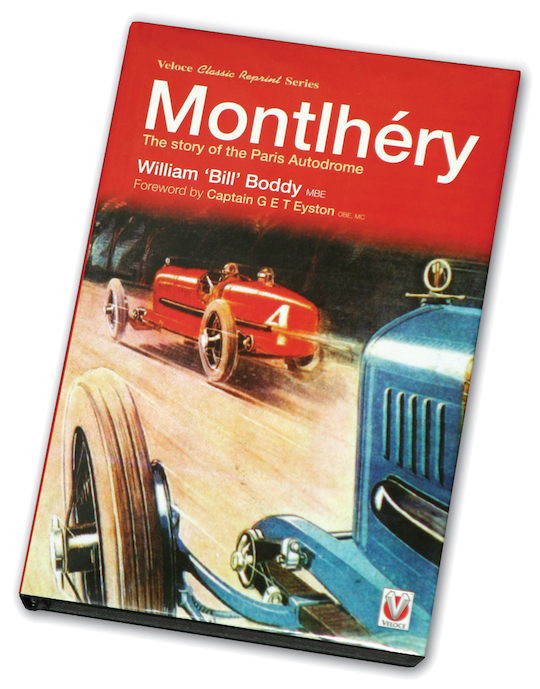

Note: The second edition, containing additional material, came out in 1983. The third is basically a reprint of the second with some revision by the late author’s son, and was published by the Bugatti Trust in 1994. Each edition has a different dust jacket photo and the one shown here is a repro of the 1968 first edition and depicts Moffatt’s 1924 Type 35 photographed in color by G. Nicholls. The first edition was, incidentally, not intended for sale in the US.

Copyright 2015, Bill Ingalls (SpeedReaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter