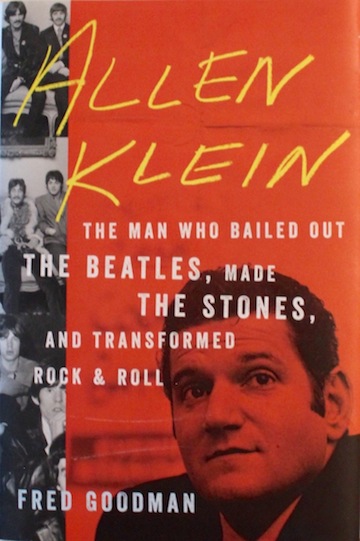

Allen Klein

The Man Who Bailed Out The Beatles, Made The Stones, and Transformed Rock & Roll

“He’s only been here three months and he’s sorted out seven years of crap!”

—John Lennon

Were you at Woodstock? I mean the town. I mean recently. In this tranquil upstate New York community, you can still find a flock of aging hippies, old men with grey ponytails and faded tie-dyes and old women with their granny skirts and hemp sandals. My guess is, assuming sparks of memory and coherence still glow up there in the embers of their minds, that if you were to ask them for an opinion on Albert Grossman and Allen Klein, you would receive for your trouble a small storm of vituperation.

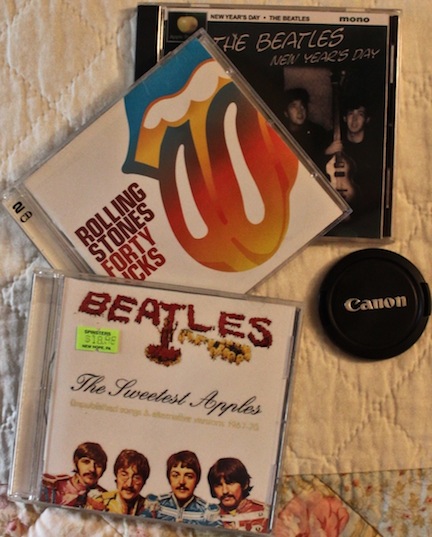

Albert Grossman, back in the day, managed Peter Paul and Mary—and Bob Dylan. Grossman was reputed to be arrogant and unpleasant, but nonetheless protective of his clients and exceedingly savvy, able to procure favorable financial deals for them. Allen Klein was cut from the same cloth and had the same reputation. He managed Sam Cooke, Bobby Vinton—and later moved from Rock & Roll to Rock, becoming deeply involved in the contractual and financial lives of the Rolling Stones; and, later, finally achieving a vital personal goal, Klein maneuvered to manage much of the monetary and legal affairs of the Beatles. For the hardcore hippies of the 1960s and 1970s, those who would cry to Bill Graham that music should be free (it isn’t), Grossman and Klein were the villains, the greedy suits who exploited the artists under their care, who represented a necessary evil that the hip longhairs and groovy musicians had to endure. But that, aging Woodstock hippies notwithstanding, is a rosy, unrealistic, skewed and narrow assessment of the real situation. We all heard stories of the gross excesses of the newly rich Rock superstars, and, later, we learned how many of them, especially the important survivors, became quite knowledgeable and interested in their financial affairs, leaving the old hippie disdain for wealth in the fairyland of lost ideals and hazy optimism. Although Dylan was likely aiming his barb at the suits, his “money doesn’t talk, it swears” has as much to do with himself. A few years back I recall seeing a photograph of a well-known rap star—Lil Wayne perhaps? In his left hand, he holds a huge roll of money; with his right hand he proffers the middle-finger salute. It would be tempting to Photoshop Klein’s face into that image, but the story is much more complicated and nuanced than that.

With very few exceptions, this is how the Rock & Roll business worked before being “transformed”: In the Brill Building and a bit uptown at Don Kirshner’s Aldon Music offices, teams of writers (Neil Sedaka, Carol King, Gerry Goffin, Cynthia Weil, Barry Mann, Elli Greenwich et al) would labor, hard and competitively, to create song after song. The best of these would be sold to the handlers of a suitable pop singer or vocal group and the record companies would produce, manufacture, and distribute the records. For the most part, the artists found themselves on the short end of the money stick. Grossman and Klein changed that equation—Klein coming on the heels of Grossman. With contractual acumen, accounting skills, bold maneuvers, brash and bullying behavior and a whole lot of chutzpah, Klein went toe-to-toe with the suits from RCA, Decca, Capital and others, negotiating monetarily adventitious contracts for his clients, securing the copyrights for them, and getting them creative control. One scheme was to have the artists self-publish, produce the records themselves, and lease the product to the record companies for distribution. Often these arrangements were complex, often with companies within companies to handle the various facets of the operation. Usually the artist would be quite pleased with the new windfall—and it wouldn’t be until later down the road, often years down the road, that they found that Klein’s share all but eclipsed their own. Klein ended up controlling the American rights to the the Rolling Stones’ early catalog. With the advent of CDs, then MP3s, and the amazing endurance of the band, this was a virtual goldmine for Klein’s ABKCO.

With very few exceptions, this is how the Rock & Roll business worked before being “transformed”: In the Brill Building and a bit uptown at Don Kirshner’s Aldon Music offices, teams of writers (Neil Sedaka, Carol King, Gerry Goffin, Cynthia Weil, Barry Mann, Elli Greenwich et al) would labor, hard and competitively, to create song after song. The best of these would be sold to the handlers of a suitable pop singer or vocal group and the record companies would produce, manufacture, and distribute the records. For the most part, the artists found themselves on the short end of the money stick. Grossman and Klein changed that equation—Klein coming on the heels of Grossman. With contractual acumen, accounting skills, bold maneuvers, brash and bullying behavior and a whole lot of chutzpah, Klein went toe-to-toe with the suits from RCA, Decca, Capital and others, negotiating monetarily adventitious contracts for his clients, securing the copyrights for them, and getting them creative control. One scheme was to have the artists self-publish, produce the records themselves, and lease the product to the record companies for distribution. Often these arrangements were complex, often with companies within companies to handle the various facets of the operation. Usually the artist would be quite pleased with the new windfall—and it wouldn’t be until later down the road, often years down the road, that they found that Klein’s share all but eclipsed their own. Klein ended up controlling the American rights to the the Rolling Stones’ early catalog. With the advent of CDs, then MP3s, and the amazing endurance of the band, this was a virtual goldmine for Klein’s ABKCO.

When wooing a potential client, Klein would ask him what he most wanted; the inevitable reply: “Money.” By offering and delivering large short-term disbursements, the artists found in Klein a savior. But then, again, what of the tale concerning Bobby Vinton? He returned “to his Long Island home one afternoon to discover a moving van and crew of workers emptying his house of its furnishings.” Calling Klein—Klein fudged and put the blame elsewhere. Klein was far from being completely honest with anybody. The book outlines in detail all of the ploys Klein used to snag the Stones and, later, how he fulfilled his dream of managing the Beatles, ironically when the Beatles were close to dissolution. He sincerely loved John Lennon, respected Yoko Ono as an artist, admired the work of Ringo Starr and George Harrison, and he helped them navigate their profitable solo careers. Paul McCartney neither liked nor trusted Klein, hired the Eastmans to manage his affairs instead, thereby tangling the large skein of the Beatles’ contractual entwinements all the more.

For his Mansion on the Hill, a book focusing on the finances of Rock during the heyday of the Springsteen era, Fred Goodman received the Ralph J. Gleason Award; his work has appeared in Rolling Stone. He writes cleanly and adroitly; he presents anecdotes, facts, back-stories and personalities in a professional and readable fashion. He keeps moving the overall story forward clearly and shows a knack for objectivity, finding the heart of every phase of Klein’s life and career. Klein, perhaps more than warranted, is shown in a compassionate light, especially in the poor-foundling-to-music-mogul motif. Only imagine if it were Albert Goldman writing Klein’s biography—think of the hatchet job he did on Lennon back in 1988. With Goodman, however, the viewpoint, although tending to gloss over Klein’s more insalubrious ploys and deceptions, holds a balance, and you get somehow to actually like Klein despite his ugly shenanigans and ethical lapses.

The book is indexed and has sixteen pages of b/w photos highlighting Klein’s childhood, rise to fame, and ultimate success. The design of the front of the dust jacket seems a bit random, but, with its red monochrome photograph and the large yellow title font, it gets the job done. The back cover is clever, with its lengthy excerpt on a seemingly distressed and creased sheet of paper. For both Stones and Beatle fans, the book tells their stories from yet another viewpoint. And for the more general Rock aficionados, the book opens a large window into the back rooms, the money rooms, of the music business and therein shines a light.

Copyright 2015, Bill Wolf (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter