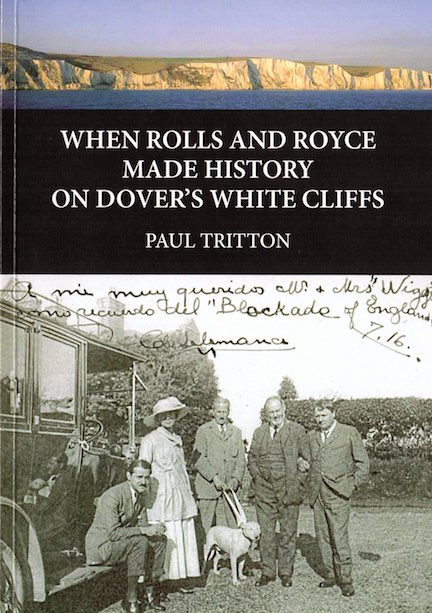

When Rolls and Royce Made History on Dover’s White Cliffs

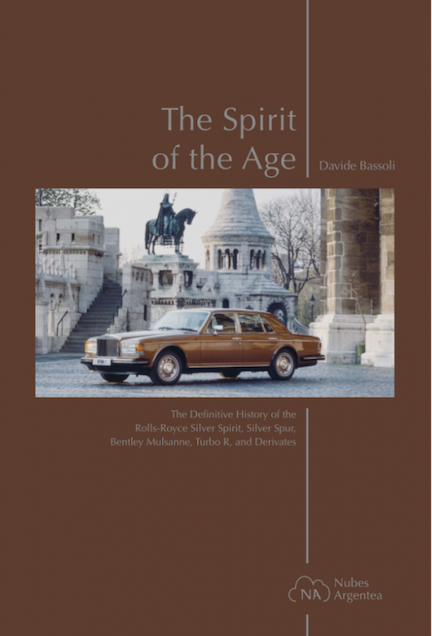

Commissioned to recognize the centenary of Rolls-Royce’s first aero engine, this book is best seen as a fairly specialized look at details within details; in other words, it is not—nor does it have to be, given that such treatments exist aplenty—a fully fleshed out overall synopsis of the storied firm and the men that tended to its fate. From the first to the last sentence, the book assumes a reader’s fundamental if not thorough familiarity with such matters.

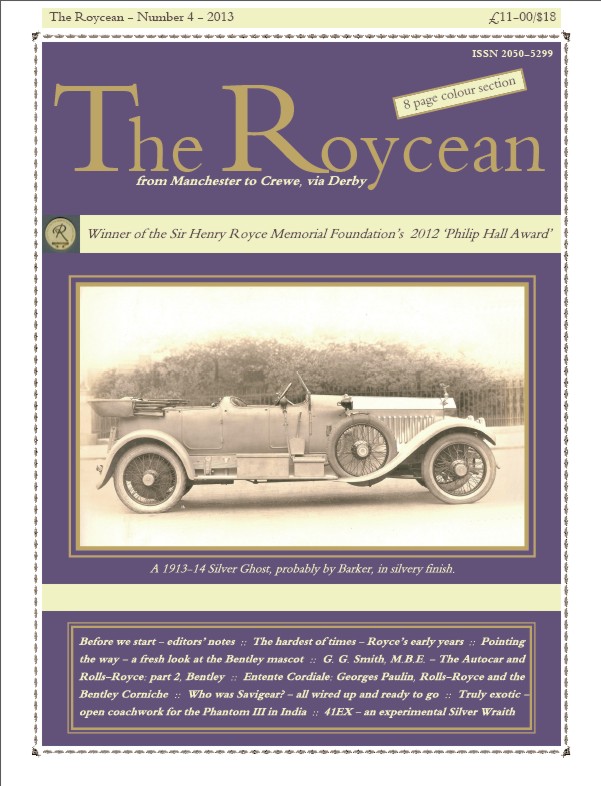

Most readers steeped in Rolls-Royce history have some awareness of company cofounder Henry Royce working in Manchester and Derby, and later at his home and design studio in coastal Sussex, as well as his villa in the south of France. But the Rolls-Royce connection to Kent, the “garden of England,” is less well known. For Kent historian—and Rolls-Royce specialist—Paul Tritton this was a glaring gap that needed to be filled. His new book is the culmination of decades of work into that short but heroic period either side of World War I that played directly into the sort of company Rolls-Royce became.

Paul Tritton’s name is well established as the author of pioneering biographies of Henry Edmunds (a friend of Edison who introduced Rolls to Royce), of the 2nd Lord Montagu (so closely connected to the Spirit of Ecstasy story) and innumerable articles on famous figures in the company.

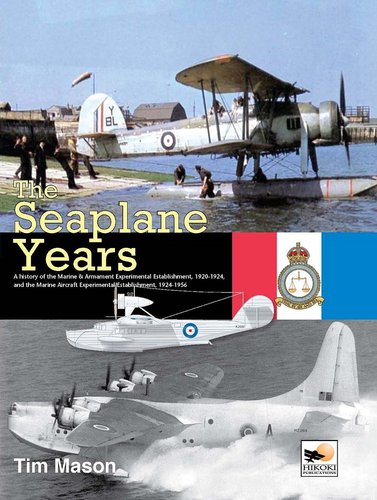

The beginnings in Kent lay as early as 1904 when C.S. Rolls drove the Duke of Connaught to a military occasion in Folkestone, using the first Royce car borrowed from Royce Ltd. In the early years of aviation C.S. Rolls came to Eastchurch on the Isle of Sheppey in 1909 to learn to fly. Within a short time he had achieved immortality by being the first man to fly from Dover to France and back in a double crossing. Just a few years later, in 1913, managing-director Claude Johnson bought the magical “Villa Vita” at Kingsdown, on the cliffs above Dover—he used it at first for weekends only; and that same year Royce rented a house in St Margaret’s at Cliffe next to Kingsdown in the period when he and his wife had separated. This little community expanded—Royce moved to a bigger house nearby which he renamed “Seaton” from his childhood recollection of a related family house. He brought some of his designers to the village, and meanwhile the newspaper magnate Lord Northcliffe, a staunch promoter of Rolls-Royce and friend of Johnson, had a house at Broadstairs further up the coast.

When war broke out in August 1914 Royce could not return to his new French villa and so it was at St Margaret’s that Royce did most of his major designing until the move to West Wittering in late 1917. It was at “Seaton” that the world’s first V-12 aero engine was conceived and designed, the Eagle, and it was put into production in record time. Other aero engines followed but it was the Eagle that set the company on the path that it remains on today as one of the world’s greatest aero engine manufacturers.

The Kent period is rounded off with the moving story of Claude Johnson’s circle at “Villa Vita” until his death in 1926, a life centered on both business and his cultural interests. It was his friends in the world of art and music that gave the house new purpose and it was from here that Johnson himself published several books as well. The book ends with coverage of Royce’s companion Ethel Aubin, more detail on Northcliffe, and other Dover links to Rolls-Royce such as coachbuilders Palmer and the hovercraft that operated from the port.

As we expect in all books by Tritton, a writer for more than six decades of books ranging from local history to Rolls-Royce, from how Queen Victoria’s voice was recorded to the films of Powell and Pressburger) the wealth of detail is impressive and he has an ear for the human side of any story. Rolls and Royce did indeed make history near the White Cliffs of Dover and this book captures it definitively.

Copyright 2020, Tom Clarke (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter