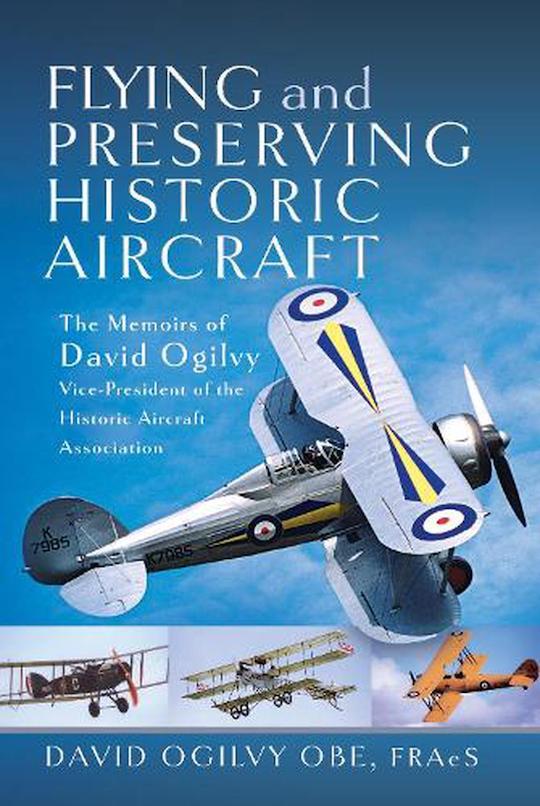

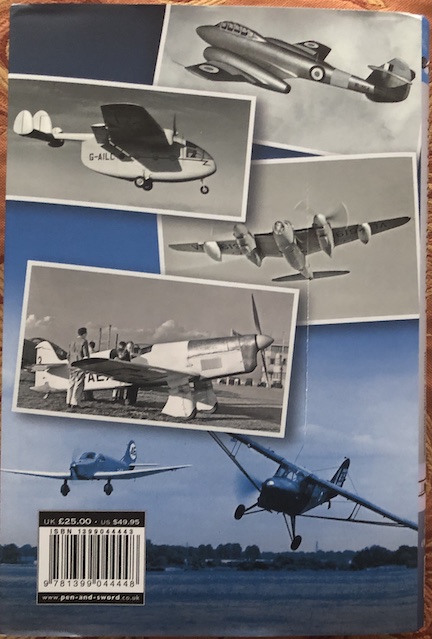

Flying and Preserving Historic Aircraft, The Memoirs of David Ogilvy

by David Ogilvy

by David Ogilvy

“One fact that I failed to find until some time later was the safe limit of bank. For my first approach I made a rather ragged final turn that upset me and the aeroplane. Attempting to line-up on the into-wind landing path, I used too much bank and for a stressfully long time the lowered wing refused to come up. When eventually I had the relevant bits pointing in roughly the right direction for a powered approach, the touchdown itself was smooth and straightforward, except that an almost aggressive pull back on the wheel was needed to persuade the package to adopt the required landing attitude.”

First impression: clever wordsmithing!

Second impression: he can’t be talking about a modern aircraft.

What is this all about? Easy, tiger, this is not a snide remark by the reviewer but how the author titled his Introduction to the book. It’s as to-the-point as the titles of chapters 1 and 2: “Why Me?” and “What Now?” But they don’t answer those questions all that clearly, partly because the book proper is too low-key to come right out and establish the author’s bona fides. That’s buried on the book jacket but if you’re in the habit of skipping that, you would have missed the long list of Ogilvy’s professional activities which earned him an OBE in 1996 for “services to aviation”—and also that he died the very year his memoir came out (it doesn’t tell you that he died in fact a few months prior to the November 2023 release, or that he lived to the ripe old age of 94).

In UK aviation circles, especially light aviation, Ogilvy counts as one of the most influential people, having co/founded a number of organizations and headed others and all-around shaped how aviation is “done” since the 1950s. Among other things, he was AOPA UK’s longest-serving officer, doing over the course of 45 years “every job apart from the accounts.” And it is the handling reports he wrote for their magazine, of which he served as editor, that constitute the core of this book. They are here fleshed out with brief notes about an aircraft’s development and history. As the name implies, these informal flight reports are assessments from the pilot’s perspective, of “a range of yesteryear’s aeroplanes,” and the style in which they are written presupposes fundamental airmanship abilities on the part of the reader.

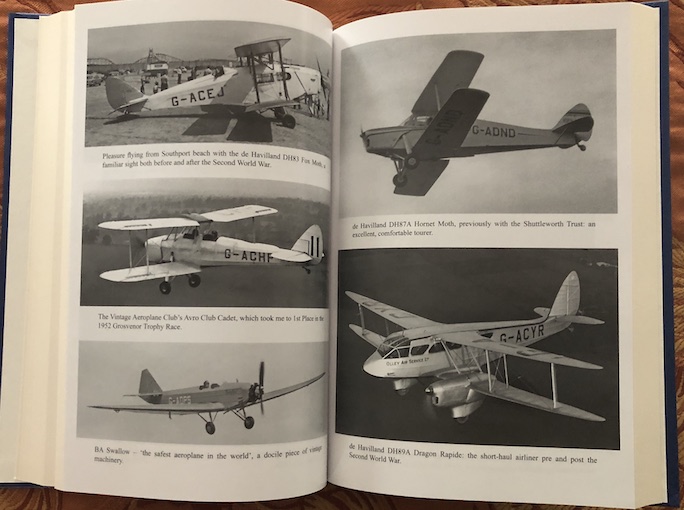

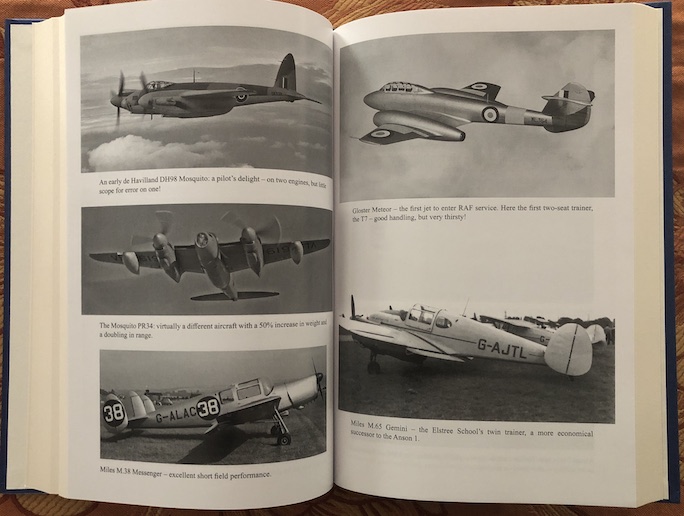

Time to test your aircraft spotting skills. Here are the names, you figure out which goes where (above and below): Meteor – Dragon Rapide – Swallow – Hornet Moth – Fox Moth – DH98 Mosquito – Mosquito PR34 – Gemini – Club Cadet – Messenger.

However, even armchair flyers will be intrigued by Ogilvy’s hands-on impressions of anything from the 1910 triplane referenced in the introductory quote above (actually a replica, as no flyable originals exist) to early jets. In quite a number of cases, Ogilvy was able to get his hands on the only extant example of a type, not least as General Manager (appointed 1966) of the famed Shuttleworth Collection. While peripheral to the story, readers who are aware of the outsize, decades-spanning contribution this organization has made to the preservation of vintage aircraft will be staggered to learn of Ogilvy’s predecessor’s shenanigans to undermine his work, and also how the whole setup of the Richard Ormonde Shuttleworth Remembrance Trust treated “airplanes as a relatively unloved entity” relative to the charity’s vast agricultural activities.

What will strike a modern reader most is the entirely different aviation environment of Ogilvy’s time: minimally controlled airspace, rudimentary air traffic control and airfields, and maintenance and licensing/certification requirements that are far less regulated. Non-UK readers will also marvel at the ease with which active Service pilots were allowed to pursue private flying opportunities, even for hire—Ogilvy did photo and ferry work, testing, air racing, air shows, founded or worked at flying schools and clubs, even bought and sold aircraft parallel to serving in the RAF and only hung up his uniform when all those other other gigs became too time-consuming.

The aircraft, military and civilian, span some four decades and are presented more or less in chronological order, and range from trainers to transports to specialized single-seaters. Each is covered in its own chapter of several pages. One thing the aircraft have in common is that all powered; there are about three dozen and they were selected for how their respective characteristics influenced “the progressive development of the flying machine.” Ogilvy calls his book an “aerobiography” and that sounds just right.

The aircraft, military and civilian, span some four decades and are presented more or less in chronological order, and range from trainers to transports to specialized single-seaters. Each is covered in its own chapter of several pages. One thing the aircraft have in common is that all powered; there are about three dozen and they were selected for how their respective characteristics influenced “the progressive development of the flying machine.” Ogilvy calls his book an “aerobiography” and that sounds just right.

Non-pilots will probably be puzzled how it is possible to just jump into an airplane you’ve never handled or even seen and fly it. Beholding a new-to-him aircraft, Ogilvy would never hesitate to hit up its pilot for a chance “to fly a circuit” (fuel was laughably cheap) with only the barest of briefings on its idiosyncrasies. He never did come to real harm but there were tight spots. The thing is, all “conventional” fixed-wing airplanes of his time were broadly similar in terms of control surfaces and basic instrumentation (he even tried a rotary wing, aka helicopter, which is an entirely different beast).

If none of the above rings your bell, read the book anyway, just because Ogilvy has such a marvelous way with words.

Copyright 2024, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter