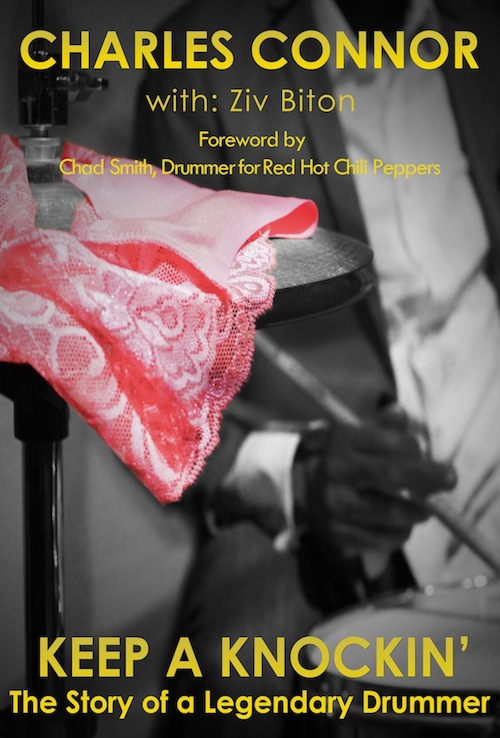

Keep A Knockin’, The Story of a Legendary Drummer

by Charles Connor with Ziv Biton

by Charles Connor with Ziv Biton

“My mother told me that before I was born, I would start kickin’ in her stomach every time a parade came by. I was surrounded by music and dance from my conception. It even affected how I spoke; I was born with a stutter, so you might say I was talkin’ in syncopation since birth.”

Drummers have threesomes all the time. Connor had his first at nine. With girls. He lost his virginity to drums much earlier. And he did lose that stutter—by being slapped in the face with a hunk of meat. Different times . . .

By the time Charles Connor (b. 1935) became Little Richard’s drummer at 18 he had already been twirling his sticks for some years. Little Richard, if you need a refresher, introduced hardcore rock ’n’ roll music to the youth of the world. In 1957 he basically blew the doors off popular music and replaced sappy hit songs such as How Much Is That Doggy In The Window with chart-topping ultra high-energy hits like Tutti Frutti, Long Tall Sally, Slippin’ And Slidin’, Rip It Up, Ready Teddy, She’s Got It, The Girl Can’t Help It, and a whole lot more. The frantic all-time drum rhythm rocker Keep A-Knockin’ featuring Connor’s famous drum intro leaves no doubt about what’s coming next. The youth of America didn’t need a weather vane to see which way the wind was blowing. Music had changed in a big way, and the teenagers of the day didn’t look back.

I was one of those teenagers that bought Little Richard’s electrifying first long-playing record, Here’s Little Richard, in 1957. My Dad hated it, of course, and forbade my playing “that jungle music” in “his” house. We compromised. I’d only play Little Richard when he was not at home. That way he could safely listen to the soothing north-of-the-border sounds of Guy Lombardo, while I went native, along with the rest of America’s youth.

In the book’s Foreword, Chad Smith, drummer for the Red Hot Chili Peppers, describes the appeal of the rhythms Connor pounded out behind Little Richard’s screaming lyrics. “It sounded like an urgent incitement to riot, a balls-out, take no prisoners call to action.” It certainly worked for me!

Later in life I started buying records by New Orleans pianist Professor Longhair. Much to my surprise I discovered in this memoir that Connor had also backed Professor Longhair as well as Sam Cook, Smiley Lewis, Shirley & Lee, Jackie Wilson, Lloyd Price, James Brown, Big Joe Turner, Champion Jack Dupree, The Coasters, and many other big-name acts of the time.

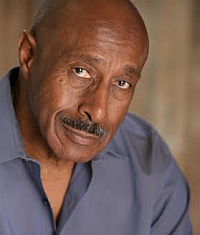

At age 80, Charles Connor is still at it—he recently was featured in a string of documentaries for BBC television about the genesis, big-bang evolution, and enduring legacy of rock ’n’ roll. Another BBC production, due to air in 2016, explores the influence of recorded music around the globe. In this documentary, the author appears with Paul McCartney, Elton John, Brian Wilson, and B.B. King. An EP, released by Connor in 2013, is appropriately entitled Still Knockin’, because he still is!

At age 80, Charles Connor is still at it—he recently was featured in a string of documentaries for BBC television about the genesis, big-bang evolution, and enduring legacy of rock ’n’ roll. Another BBC production, due to air in 2016, explores the influence of recorded music around the globe. In this documentary, the author appears with Paul McCartney, Elton John, Brian Wilson, and B.B. King. An EP, released by Connor in 2013, is appropriately entitled Still Knockin’, because he still is!

The circle remains unbroken, and closes in on a single drummer who helped pave the way for the modern age of popular music. Because Connor’s distinctive rhythms provided the basic beat behind so many popular songs, and for such a wide array of talented artists, I’m now wondering what attracted me to the music—the frontmen or the Connor rhythm? Would Guy Lombardo be popular today if Connor had played drums in his band? Would my Dad have liked the Lombardo sound even more?

The book is composed of 35 short chapters, starting with the beginnings of Connor’s drumming career. At the age of 15, he was playing in Sunday night jam sessions at the Club Tijuana in New Orleans. In 1951, at age 16, he fell backwards into heaven when he was a substitute drummer for the locally well-known and highly respected Professor Longhair, then playing at the Hi-Hat Club. The Professor liked what he heard and hired Connor for a tour. Connor dropped out of high school and never looked back, rapidly finding his way to the top with Little Richard and others.

Like so many rock ’n’ roll successes, Connor turns to alcohol and pinwheels semi-out-of-control until at age 26 he takes a break to find himself. It doesn’t work and he falls back into the music scene, but that’s another set of stories best left for the reader’s enjoyment. Even though Connor no longer drinks, each chapter reads like a bar story told over a friendly glass or two (or more) after the show.

Connor gets his point across with humor and wisdom gained, one suspects, not from a book (other than the Bible, perhaps), but from life itself. Connor becomes philosophical from time to time with insightful statements like: “A musical exhibition is communal worship of the sound through the vessel of the performer. The performer is the preacher, the audience, the congregation, the stage, the lectern, the dance— a prostration.” He also observes that in 1957, “Music venues were some of the only places where races would mingle.” In that regard, rock ’n’ roll helped pave the way for the recognition by white American youth that equal rights did not actually exist, and that they should. When your musical heroes were not allowed to drink from the same water fountain you used, it made you think about what was going on in a larger way. Something was obviously wrong with the way things were. It wouldn’t be long before Bob Dylan would point out that “the times they are a-changin’,” and they did, and still are. It’s been a long and winding road, with a ways to go yet.

Considering that a musical act, especially a live show, is all about presentation and energy and flash the book design is positively boring. Connor, rightly, stresses the importance of “selling the show” and filling the house through excellent costuming and presentation of the band and its star performer—and the same applies to books! A lavish, or at least more attentive production sells more tickets/books! The book design is meek when it could be, should be powerful. Even the cover imagery does not exactly shout out what the book is even about. In musical terms, it needs some rehearsal work to tighten up its stage presence.

Advance copies of the book came with a note that future copies would have better photo reproduction. This is not entirely unusual especially for such a new publisher. But, quality aside, photo selection is also a weak spot here. Quite a few of the photos are generic inasmuch as they illustrate Connor’s career in general (playbills, poster and magazine covers, article reproductions from various time periods etc.) rather than the specific stories he relates here. Eighteen of the book’s 45 pictures are of a personal nature, but basically fall into the category of “here I am with so-and-so” photos. There are good shots of Little Richard and a few of the other stars Connor worked with, but not much else that would help the reader visually connect with the specific stories.

If the beginnings of rock ’n’ roll interest you, and you enjoy good first-person stories told in an engaging way, don’t let my remarks about the presentation keep you from what is otherwise a fine book. Thank you Charles Connor, for telling me about your experiences. I was one of those kids looking up at the stage while you were looking out.

Have an itch to pick up the drums? Connor is still giving private lessons! At least go check out his sticks that have been on display at the Rock ’n’ Roll Hall of Fame Museum in Cleveland, Ohio into which he was inducted in 2010.

Ziv Biton is a freelancer and ghostwriter in the music field and for this book conducted interviews with Connor, did background research, and massaged everything into narrative form.

Copyright 2015, Bill Ingalls (SpeedReaders.info).

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter