How to Build a Car

The Autobiography of the World’s Greatest Formula 1 Designer

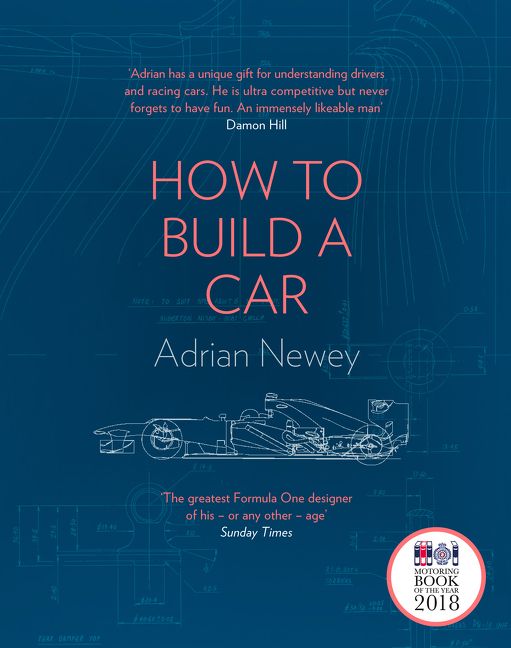

If I change a wheel on my car, let alone install a new battery, I regard it as a significant feat of engineering. So I doubted if I was in the target market for How to Build a Car because Newey has always been characterized (or should that be caricatured?) as the geek’s geek, the bald man with the supercharged brain behind countless Formula 1 innovations. Cars designed by the Stratford-upon-Avon-born Briton have won more than 150 Grands Prix and he has enjoyed a glittering career working for the big beasts of Formula 1, including Williams and McLaren in the last century and Red Bull in this one.

In common with Jeremy Clarkson (from BBC’s Top Gear and Amazon’s The Grand Tour TV shows), Newey was expelled from Repton, their posh fee-paying school, for their respective incidents of bad behavior. Newey’s took the form of surreptitiously turning up the amplifiers of visiting rock band Greenslade so high (perhaps to a Spinal Tap 11?) that the school building’s stained glass windows were damaged! Newey survived this hiccup in his education and went on to study Aeronautics and Aerodynamics at the University of Southampton, not because he was interested in aircraft but because “I wanted a career in racing.” He started work with Fittipaldi Automotive in 1980 and, before the decade was over, his name was pinging insistently on the Grand Prix radar. He had already designed the March 86C which, in Mario Andretti’s hands, had utterly dominated the 1987 Indy 500 before retiring only 18 laps from the finish. The next year saw his tightly packaged March 881 doing things in Grands Prix that March F1 cars had only rarely achieved before, such as outpacing McLarens and Ferraris. And there were no superstar drivers in the 881’s cramped little cockpit to take the credit, as neither Ivan Capelli nor Mauricio Gugelmin, although fast and capable, was quite in the premier echelon of F1 talent.

Cowritten with gentle help from a ghost writer, Newey’s autobiography describes the genesis of some of the most successful cars he has designed. All except the March 83G sports car and the March 86C Indy car are Formula 1 cars and they comprise some of the most successful racing cars of the last quarter century.

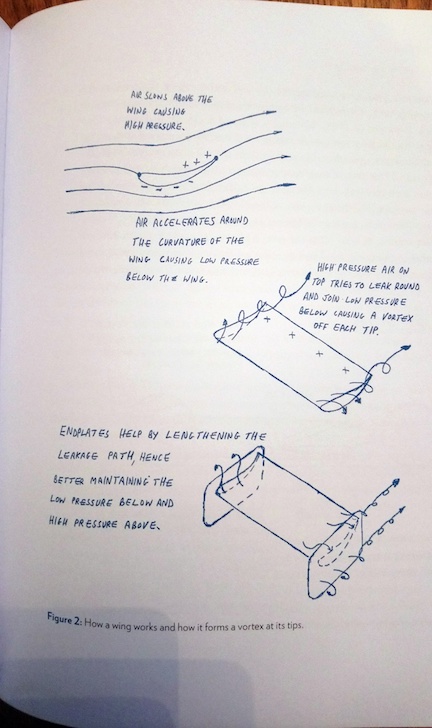

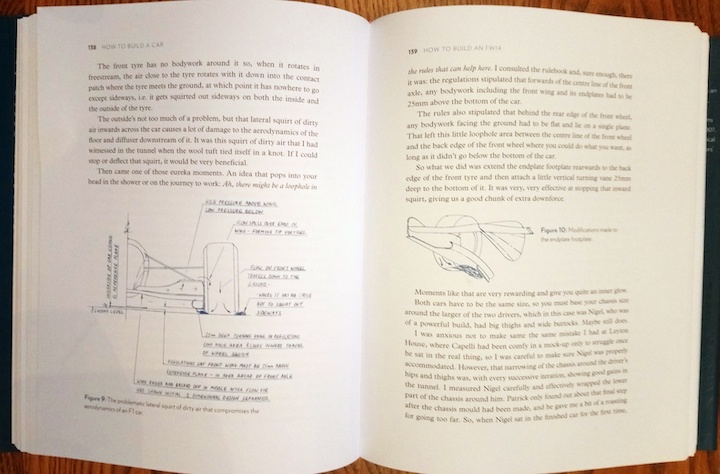

One characteristic of many really smart people is their ability to explain complex issues in terms that are easily understood by those of us whose skills lie elsewhere. I confess to being one of the worst-equipped people to understand even the big picture of ground effect, active suspension or double diffusers, let alone the minutiae of such esoteric matters as rear squish areas and boundary layer losses. But it is to Newey’s credit that not even once did I lose my way when reading his book. Far from it, in fact, as Newey’s ceaseless search for perfection makes for an absorbing and fulfilling read.

The book is divided into eleven sections, rather archly called “turns,” that comprise accounts of the design of individual cars, starting with the March 83 G GTP sports racer and ending with the Red Bull RB 8 Formula 1 car. The “turns” are further divided into 77 short chapters, making the book beguilingly easy to read, especially as the language used is so simple. It’s a very effective approach and, more than once, I was reminded of British author Nick Hornby’s almost conversational prose style. (US readers are most likely to be aware of Hornby’s work from the film adaptions of his novels, High Fidelity and About a Boy. Hornby was also nominated for an Oscar for the script of Brooklyn.) An example of how simple Newey can make it for the non-technical reader is his description of gear-dogs: “You can picture a gear-dog if you interlock your fingers and then try to slide your left hand past your right hand. That’s exactly what a gear-dog does. It allows the torque from the shafts within the gearbox to be transmitted through the gears.” A less assured writer might take several pages to tell me less than Newey does in fewer than 50 words.

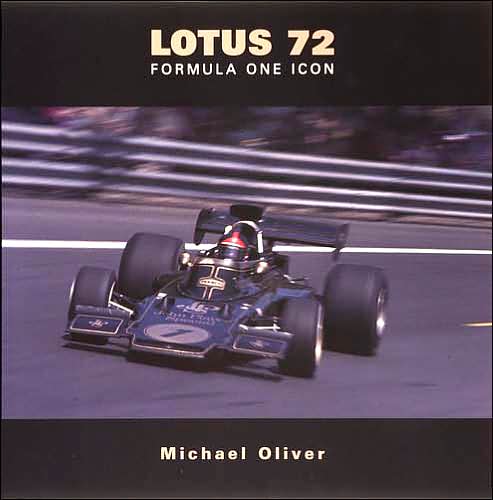

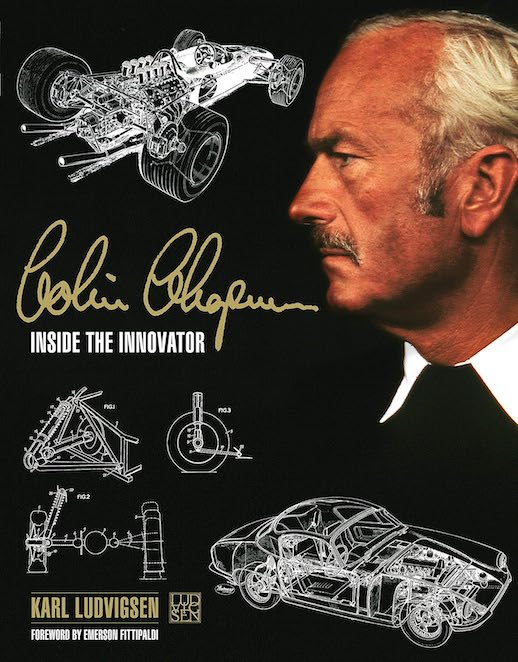

Newey confesses, very early in the book, “I’m happiest when working on a big regulation change” and, whilst there have been times during his career when such changes have taken place, F1 has increasingly stifled innovationby the imposition of crushingly prescriptive regulations. This reader is prompted to speculate on just what solutions Newey might have been able to introduce if he had worked in the more relaxed regulatory regime of previous eras of Grand Prix racing. In the Sixties and Seventies Lotus’ Colin Chapman had disrupted racing’s ancien regime with cars such as the fully stressed monocoque Lotus 25 and the ground effect Lotus 78/79 in Formula 1 and at Indianapolis the 500-winning Lotus 38. What might Chapman disciple Newey have achieved if he had been born before World War II instead of being a 1958 baby boomer?

Refreshingly, this book does not confine itself to accounts of crunching wind tunnel numbers, nor long hours spent at the drawing board—something Newey still insists on using, by the way, and always “with a 0.3 mm 4H pencil.” This book is not just about design though, but about people too, and is full of anecdotes about the drivers and team bosses with whom he has worked. And I also learned much about Newey the man, from early days helping his father build a Lotus Elan to the stress his work placed on his marriages. In 1982, his father gave him another home-built Elan as Adrian’s (first) wedding present; the honeymoon trip to the South of France added to the 170,000 miles the yellow Lotus travelled in the family’s hands. That is quite a testimony to a car whose manufacturer’s name stands, in the eyes of some heretics, for “Lots of trouble, usually serious” . . .

Refreshingly, this book does not confine itself to accounts of crunching wind tunnel numbers, nor long hours spent at the drawing board—something Newey still insists on using, by the way, and always “with a 0.3 mm 4H pencil.” This book is not just about design though, but about people too, and is full of anecdotes about the drivers and team bosses with whom he has worked. And I also learned much about Newey the man, from early days helping his father build a Lotus Elan to the stress his work placed on his marriages. In 1982, his father gave him another home-built Elan as Adrian’s (first) wedding present; the honeymoon trip to the South of France added to the 170,000 miles the yellow Lotus travelled in the family’s hands. That is quite a testimony to a car whose manufacturer’s name stands, in the eyes of some heretics, for “Lots of trouble, usually serious” . . .

Newey turns out to be a much less buttoned-down man than I had expected and I was especially taken by his account of two incidents that illustrate this. The first was in 1997, shortly after he had started work for McLaren: “. . . grey was Ron’s [Dennis] favourite ‘colour’ Everything in the factory was grey . . . Even the call sign of his aircraft was GREY.” So what did Newey do? He had his office redecorated in duck egg blue with a tan carpet. Ron Dennis was not amused: “My God, he’s going to have a heart attack” thought Newey, after his outraged boss had turned deep red and then a no less wholesome purple. The second incident Newey recounts shows that the drawing office genius hadn’t fully left behind the sort of bad boy high jinks that had gotten him reprimanded at school. He celebrated Red Bull’s British GP win in 2009 by doing donuts in a brand-new Ferrari California owned by supercar dealer Joe Macari on the lawns of his team boss Christian Horner’s home, a Georgian country vicarage. This happened after what Newey rather coyly recalled as “one or two (three or four) drinks.”

Adrian Newey knows how to have fun on track too, enjoying success in historic racing in cars such as a lightweight E-Type, a Ford GT40, and a Lotus 49. As he puts it “My childhood dream car, the first car I’d ever built as a 1:12 scale model . . . to be racing an ex-Graham Hill Lotus 49 around Monaco is as good as a fulfilled childhood dream ever gets!” The Lotus 49, chassis R8, had first appeared in the Tasman series at the New Zealand Grand Prix held in January 1969 and, nearly half a century later, I interviewed Classic Team Lotus boss (and son of Colin, of course) Clive Chapman and he told me how “Adrian really wanted the car (the 49 ) to be accurate as it was in period . . . and did a lot himself. He had his first run at (Lotus base) Hethel, and it was a bit surreal for Adrian to be asking set-up advice from Chris (Dinnage, with Lotus since 1982 ).” One legend meeting another—I think that says a lot about Adrian Newey. How I wish that a mere civilian like me could have witnessed those first few shake-down laps of a car that heralded the hegemony of the Cosworth DFV in 1967.

I overcame my scepticism that this book was not for the likes of me before the end of the first page. I rarely reread non-fiction but this book is an exception, and I am still learning from it. And the price is a bargain but realize that in its cheapest version, the Kindle edition (the only version available in the US), you’ll be missing the impact of Newey’s hand-drawn illustrations that are absolutely key to getting the most from the book and also to getting an insight into how he thinks and expresses himself.

I overcame my scepticism that this book was not for the likes of me before the end of the first page. I rarely reread non-fiction but this book is an exception, and I am still learning from it. And the price is a bargain but realize that in its cheapest version, the Kindle edition (the only version available in the US), you’ll be missing the impact of Newey’s hand-drawn illustrations that are absolutely key to getting the most from the book and also to getting an insight into how he thinks and expresses himself.

If you are interested in discovering how “the black art of aerodynamics” can be exploited to enable the modern Formula 1 racing car to corner at 6 g and to brake at 5 g, then you really need to read this book. If nothing else, it is proof that Stratford-upon-Avon may have produced not one, but two Bards, and so . . . All’s Well that Ends Well.

Copyright 2019, John Aston (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter