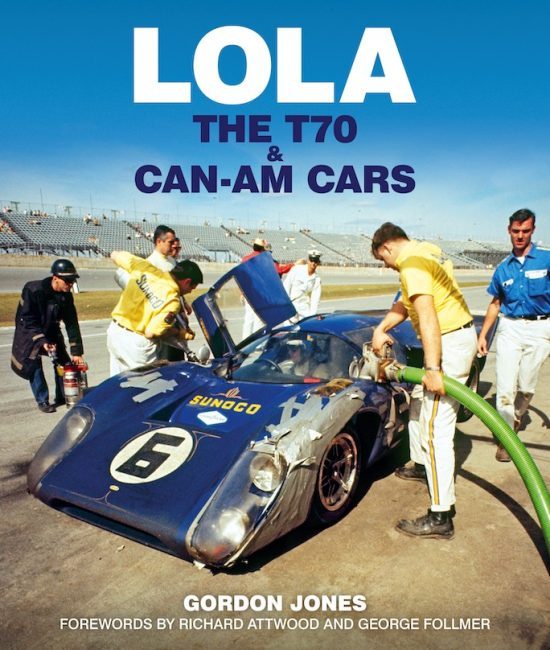

Lola: The T70 and Can-Am Cars

by Gordon Jones

by Gordon Jones

“Yes, lovely car the Lola T70, went exactly where you pointed her.”

—George Follmer

The 1968 Tourist Trophy at Oulton Park was the first international motor race I attended, and it was won by Denny Hulme in a Lola T70. Thanks to this new book I now know that the car’s chassis number was SL 73/102 and that the car suffered from gearbox failure in the Norisring’s 200 Meilen Von Nurnberg three weeks later, attesting to the fact that author Gordon Jones’ book, forty years in the making, is not lacking in detail. This is a huge book—6.5 pounds, 12 x 10″ and running to 576 pages. It is beautifully produced, as one has come to expect from Evro, the page layout is clear and reader friendly and the forensic detail of the text is (thankfully) leavened by hundreds of period photographs, mainly in color.

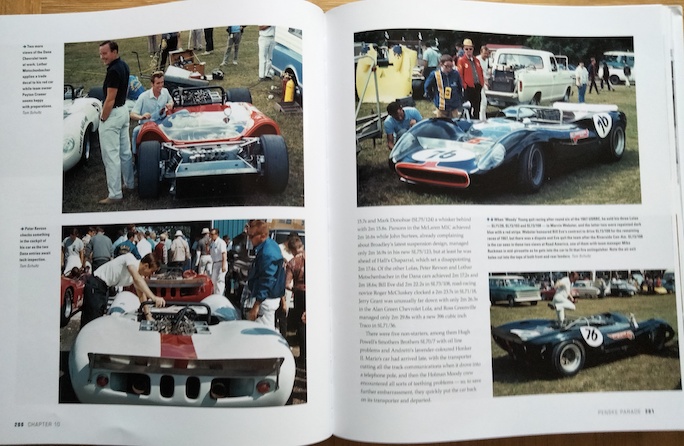

I read this book from cover to cover, because not to do so would have been a discourtesy to both author and publisher. But I would not recommend that every reader has to do the same, unless they want to be assailed by a blizzard of facts. This is a book to consume in small doses, perhaps to research the glory days of Can-Am, or to ascertain the slings and arrows of fortune that beset a particular car or to remind oneself how, back in the Sixties, even the UK’s minor circuits, like Croft and Mallory Park, echoed to the thunder of Lola V8 sports racers driven by members of the racing aristocracy, such as Bruce McLaren and Brian Redman.

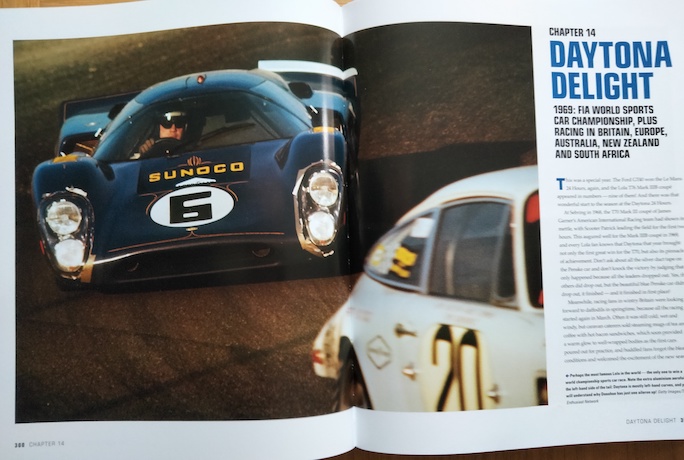

The author writes in a crisp, almost dry style and tells the story of the T70, its antecedents and successors from the Lola Mark 6 GT in 1963 to the T260 which raced during Can-Am’s death throes in 1974. Most of the content comprises a season-by-season, race-by-race analysis of major races (and some not so major at all) in Europe, the United States, South Africa, and Japan. And, as if that were not quite enough, there is also a 46-page appendix of race results, including chassis number, entrant, and driver/s. The book is unleavened by much opinion or commentary, with the exception of a few relatively whimsical photograph captions. The Appendices also include a very readable discussion about how America’s ubiquitous pushrod V8 came to be developed at such a feverish pace in the decades following WWII. To a British reader, even the names of the dramatis personae in this saga evoke the thunderous back beat of a tuned V8 under a blue Californian sky—names like Al Bartz, Traco, Ed Iskenderian, and Hank the Crank.

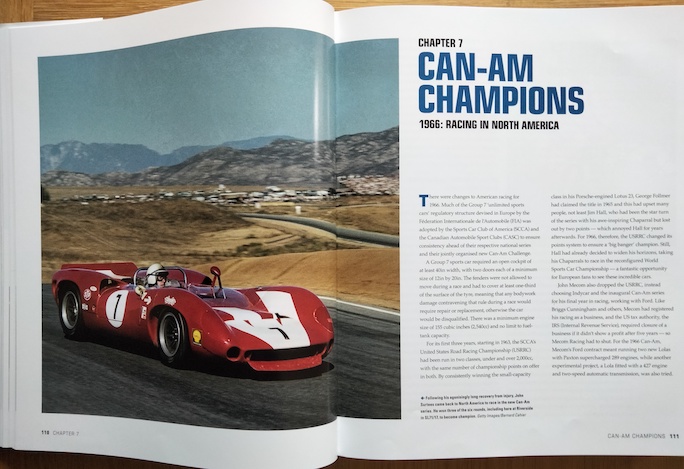

Although the T70 Mk 111B is probably the definitive Lola to the modern eye, the book is about so much more than the marque’s star turn. Some might dismiss Can-Am as The Bruce (McLaren) and Denny (Hulme) Show but it was John Surtees’ T70 that won the series in its first year, 1966, and in Jackie Stewart’s hands, the L&M-liveried T260 was still threatening the McLaren hegemony in 1971.

There is no doubt that this book represents the fruits of a labor of love by Gordon Jones and I can barely imagine the amount of source material he must have waded through between conception and publication. Was it all worth it, for the car which, in the author’s words, “had had its day by 1971”? Of course it was, because the T70, especially in (you guessed already) Mk 111B form, not only beguiled the racing community in period but has continued to do so ever since. But that does itself raise the question as to why there is only the most fleeting of references to the T70’s near ubiquity in contemporary historic racing. Historic events do not “count” in the sense that the FIA World Sports Car Championship did in the Sixties, but historic racing has risen in status from an eccentric sideshow to mainstream acceptance, with events such as the Goodwood Revival and Classic Le Mans enjoying bigger audiences than many Grands Prix. The provenance and authenticity of historic race cars has always been problematic and has been made more so by the admissibility of continuation models and replicas, but I would like to have seen at least an acknowledgment of the T70’s long “afterlife.” Perhaps the author’s take on the subject can be gleaned from his splendidly dismissive comment about Carlos Avallone’s T70, which had burned “to a pile of ash” at Interlagos in1972: “Photographs of the remains make one wonder how a car racing today as SL76 /153 can carry that identity.”

There is no doubt that this book represents the fruits of a labor of love by Gordon Jones and I can barely imagine the amount of source material he must have waded through between conception and publication. Was it all worth it, for the car which, in the author’s words, “had had its day by 1971”? Of course it was, because the T70, especially in (you guessed already) Mk 111B form, not only beguiled the racing community in period but has continued to do so ever since. But that does itself raise the question as to why there is only the most fleeting of references to the T70’s near ubiquity in contemporary historic racing. Historic events do not “count” in the sense that the FIA World Sports Car Championship did in the Sixties, but historic racing has risen in status from an eccentric sideshow to mainstream acceptance, with events such as the Goodwood Revival and Classic Le Mans enjoying bigger audiences than many Grands Prix. The provenance and authenticity of historic race cars has always been problematic and has been made more so by the admissibility of continuation models and replicas, but I would like to have seen at least an acknowledgment of the T70’s long “afterlife.” Perhaps the author’s take on the subject can be gleaned from his splendidly dismissive comment about Carlos Avallone’s T70, which had burned “to a pile of ash” at Interlagos in1972: “Photographs of the remains make one wonder how a car racing today as SL76 /153 can carry that identity.”

I have one other minor cavil. I was a little disappointed that there was not more about the experience of actually driving a T70. The number of drivers who raced them in period is diminishing every year, but I am surprised that recollections from drivers such as David Hobbs and Brian Redman were not included. Race records are important, but first-hand experience can add glister to the story.

This is not a book I would want to re-read front to back in its entirety, but it won’t be permanently exiled to the bookcase. What will make this book irresistible is the galaxy of wonderful period pictures. Of course the car is the star but, just like Rainer Schlegelmilch’s wonderful Sports Car Racing 1962–1973, it is the unwitting testimony of a past era that beguiles. The laid-back, all-access informality of pit and paddock is in such sharp contrast to the corporate rigor that pervades modern motorsport. And looking at the images of clean-cut, all-American boys, whether “Captain Nice” Mark Donohue or an earnest young paddock visitor, it’s hard to believe that at the same time, albeit in a parallel universe, Haight Ashbury, Laurel Canyon, and Woodstock were adding another chapter to the story of the Land of the Free. The T70 was the Bruce Springsteen to the Ferrari P4’s Luciano Pavarotti, but for many it is still The Boss. It may once have flirted with those posh folk at Aston Martin, but Le Mans 1967 showed what a disastrous marriage that was. The T70 knew its place —blue collar bruiser with a bellowing Chevy smallblock in back.

Copyright 2022 John Aston, speedreaders.info

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter

Hello & thanks for the super review. Why nothing about the historic scene? It would take another whole book, and at 576 pages the Editor said “no more”. Why no driving anecdotes? I tried but none were offered, or they have passed. Sadly it’s Altzheimers for Follmer and Hobbs. Redman really only drove in 1969 in Scandinavia, and others merely offered “Super car to drive…”

Cheers, Gordon