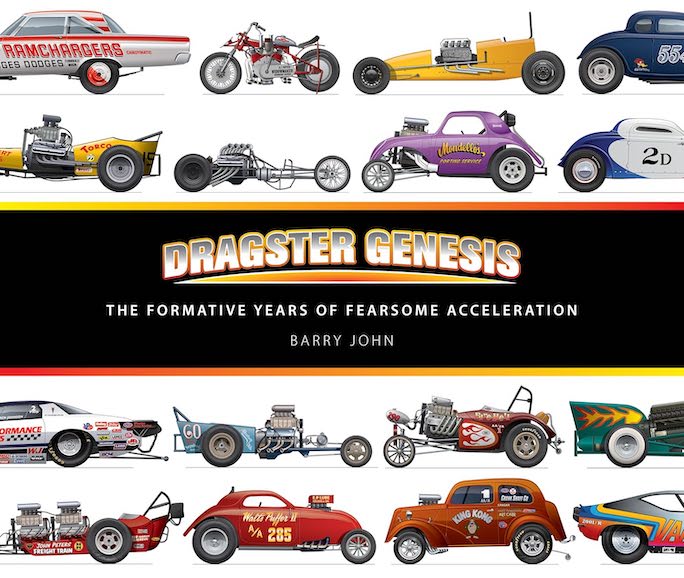

Dragster Genesis: The Formative Years of Fearsome Acceleration

by Barry John

“No wonder they call you Swamp Rat, you don’t care who you hurt as long as you make a buck on it . . . you take a green kid and put him into the biggest blown fueller you can make.“

—Serop “Setto” Postoian, Speed Sport Roadster driver, 1959

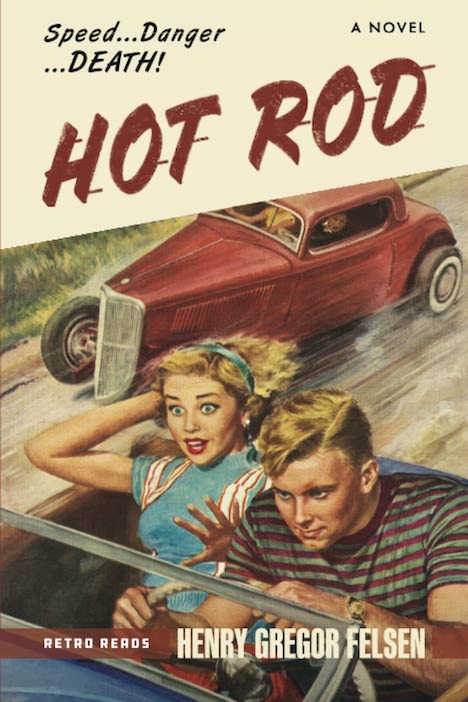

Drag racing gets poor press in Europe. It’s often dismissed as simple, easy, and requiring none of the skills needed for road racing. There’s the reek of elitism, with posh Rupert circuit racers sneering at drag racing as a blue-collar distraction, bread and circuses for the wrong crowd. But here’s the thing—if you offered me a drive in your analog-era Formula 1 (a Ferrari 312T would be just fine) I’d jump at the chance. And I’d not care a damn that I’d be hopelessly slow, nor that my poor old neck would soon expire if I ever went fast enough to finding a hint of slicks ‘n wings grip. But not for all the tea in China (or even all its EVs) would I accept your offer of a quarter mile—hell, even a burnout—in a Pro Mod, let alone a Top Fueller.

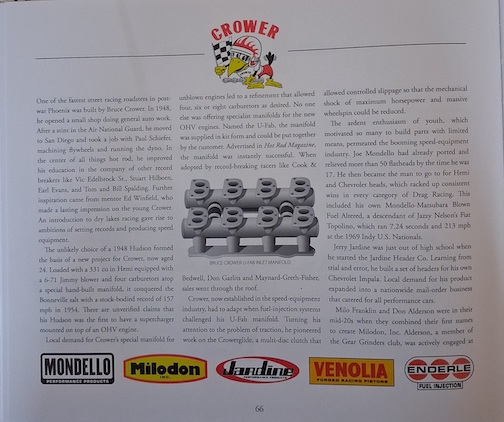

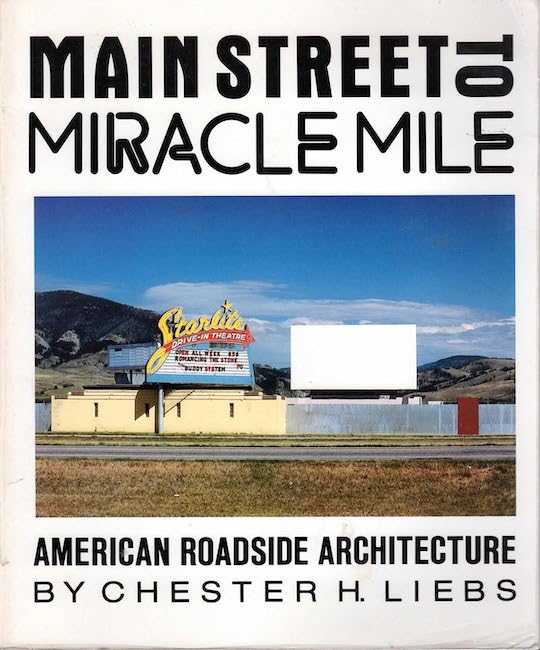

Crower’s trick manifold.

I first saw drag racing at Santa Pod, the former USAF base in the English Midlands, in 1973 and I fell for its thunderous majesty as soon as I heard an angry big block V8. Dragster Genesis is, I think, Evro’s first title on this under-appreciated branch of motorsport and it is a crackerjack of a book. But I confess I’d expected something rather different.

Drag racing is the most photogenic motorsport of all, and its horsepower- meets-showbiz spectacle led me to believe that I’d be savoring period pictures of the technicolor theater of burnouts, back-up girls, and blow-ups. Barry Johns, however, is a graphic designer and he has used his artistry to create the hundreds of illustrations in this book. And he writes prose to match the pictures; within a page you know you’re in the hands of a serious enthusiast with the skill set to convert even the most indifferent drag racing agnostic.

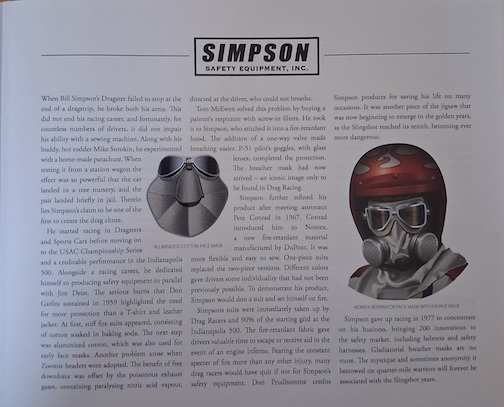

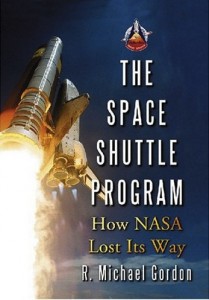

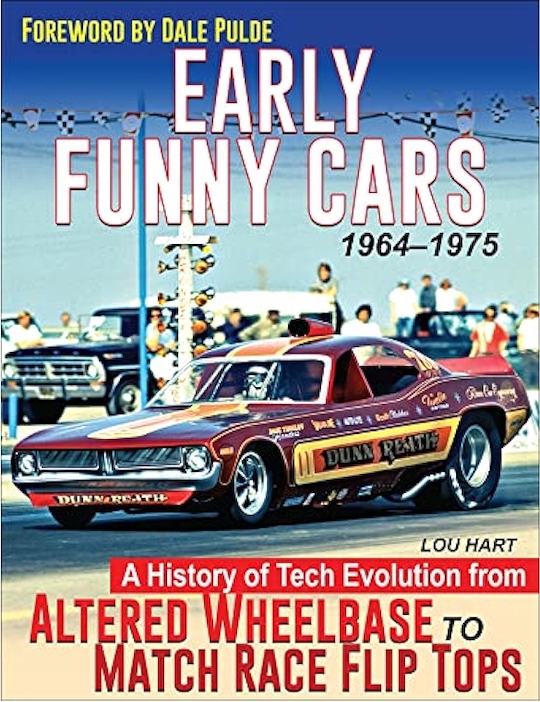

Bill Simpson’s contribution to drag strip safety.

The author describes drag racing’s, yes, genesis in the postwar years, its evolution from the outlaw domain of hot rod renegades to the big buck professional sport it was to become. Each of the hundred-plus chapters begins with a superbly drawn illustration, often, but not always, of a significant dragster from the first sixty years of the sport. The machinery—from V8 Flathead Coupes to Funny Cars, and Sixties Slingshots to 21st Century Top Fuellers—is shown in profile, and in the most extraordinary detail for such relatively small scale. And they convey the wonderfully irreverent joie de vivre of drag racing even better than photography ever could. Let your eyes linger over the profile of my random choice, let’s say Bill Jenkins’ 1972 “Doorslammer” Chevrolet Vega, called “Grumpy’s Toy”. Now drink in the detail, starting with the perfect stance, jacked-up haunches sporting immense slicks, then the steep rake to the ground-hugging hood surmounted by the gulping air intake for the small block Chevy (aka Mouse Motor, kid brother of the big block Rat and Elephant V8s).The livery is an explosion of red and white, punctuated by the names that helped create drag racing’s iconography—Cragar (wheels), Pennzoil and Wynn’s (lubrication), Hays (clutches), Manley (valves and pistons), Holley and Hooker Headers (c’mon, do I need to explain?). I grew up in the stiff upper lip, monochrome era of sober, British Racing Green race cars. Fun felt like it was still rationed and encountering the glorious frivolity of drag racing was like hearing the Beach Boys after a childhood being force-fed Perry Como.

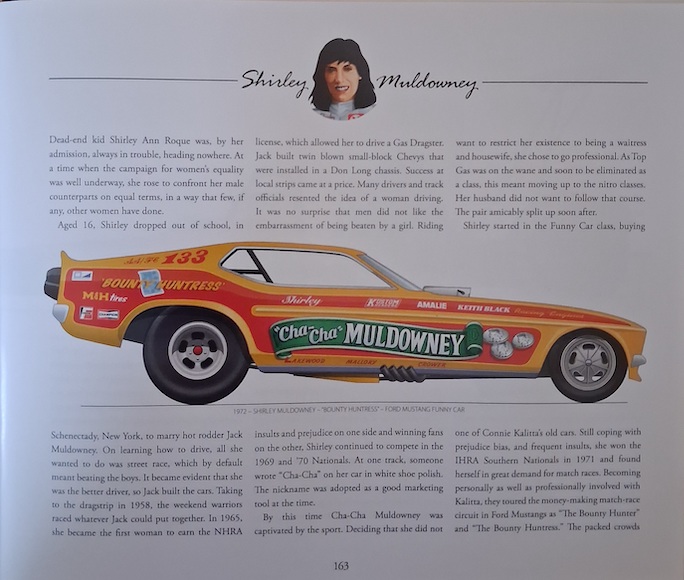

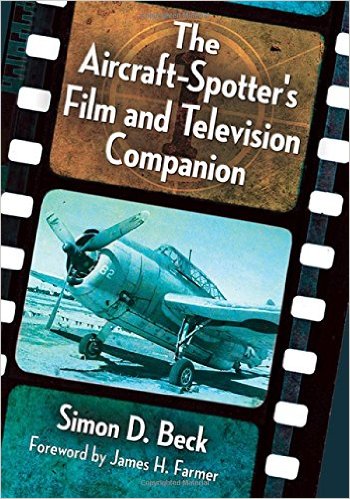

Shirley “Cha Cha” Muldowney, aka The Bounty Huntress.

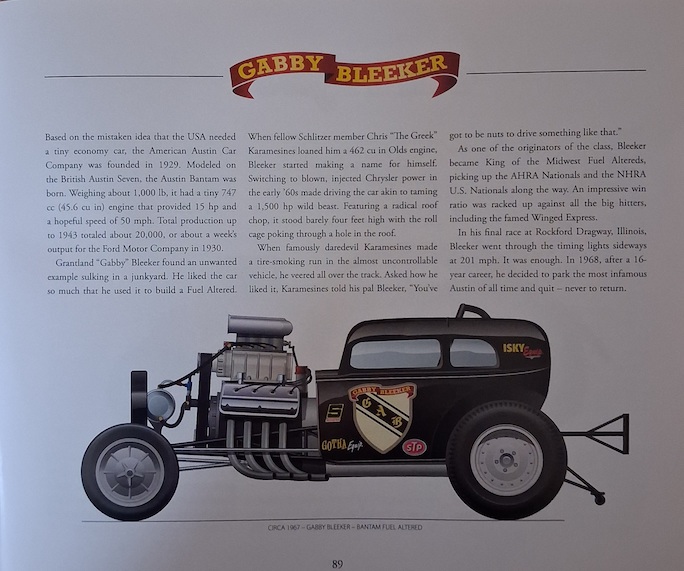

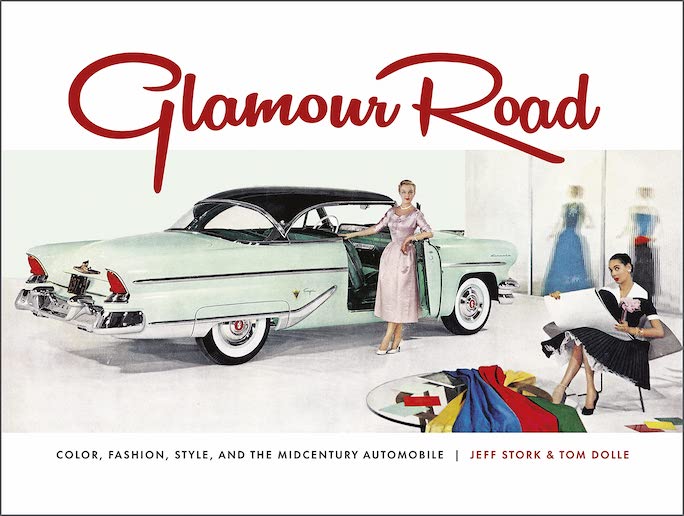

Although this landscape-format book is a modest 192 pages, the author has included a huge amount of information about drag racing’s origin and evolution. He credits the drivers even drag racing dilettantes know (Don “The Snake” Prudhomme, John Force, “Slam’n Sammy” Miller, Shirley Muldowney, and the Arfons brothers) but supplements them with the stories of lesser known but equally colorful characters. Can you think of two more perfect names than Connie Swingle and TC Lemons, Don Garlits’ assistants who helped him build Swamp Rat 14? Or Garland “Gabby” Bleeker, who created a 1500 bhp Austin Bantam fuel-altered in 1967.

Gabby Bleeker’s Bantam. “You’ve got to be nuts to drive something like this.”

It is rare in an automotive work for the societal influences on its subject matter to be addressed in such an informed way. I can think of only a handful of authors who also had the cultural and political insight to do so, notably including Stephen Bayley and Kassia St Clair. To those names can be added Barry Johns, as his grasp of the sociological stimuli and scientific advances that helped create drag racing shows profound understanding. For example, he writes about how the Oldsmobile Rocket 88 of 1949 not only rewrote the rules for affordable performance but stimulated one of the 20th Century’s greatest legacies:

“The impact of the car was underlined by Ike Turner and the Kings of Rhythm. The song ‘Rocket 88’ [recorded in Memphis, in 1951], an ode of praise, was released with his sax player on vocals. The recording, credited to ‘Jackie Brenston and his Delta Cats’ hit number one . . . and is now regarded as the first example of a Rock and Roll record.”

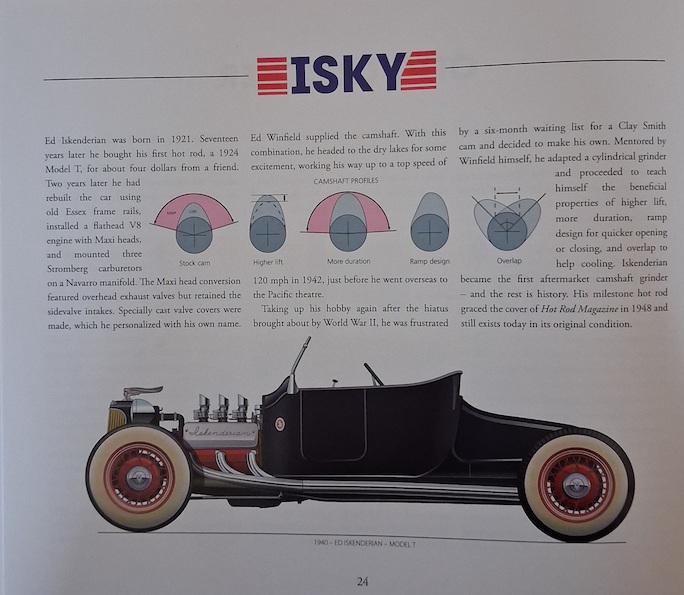

Johns knows his technical stuff too and his explanations of subjects as diverse as supercharging, nitromethane, camshaft design, and tire adhesion should be accessible to even the most non-scientific reader. I will admit that I didn’t expect to find myself enjoying reading about such erudite subjects as the design of trick diffs, parachutes and the original Christmas Tree timing light, the brainchild of Oliver Riley after a chance conversation with the NHRA’s Bud Coons in 1962. And, sorry, but that takes me right back to the wonderful diversity of personal names and product nomenclature in drag racing. I grew up in a grey and wet country peopled by race car designers called Colin or Charles, drivers called Jack and John, and car modifiers with prosaic names like “Special Tuning,” “Downton” and “Speedwell.” As a kid, I’d devour any and every American magazine, so hungry was I for color, excitement, fun and, yeah, the sheer sexiness of the West Coast in the peak of the Baby Boomer era. The Saturday Evening Post might have been staid—Norman Rockwell and “Honey I’m home”—but it still served as my gateway drug to Car and Driver and Hot Rod magazine. I didn’t then know a thing about names like Milodon, Iskenderian and Edelbrock, but you don’t need to be able to read music to enjoy a great tune, right?

It wasn’t all Fun, Fun, Fun though, and sometimes much worse things could happen than Daddy taking your T Bird away. Of course, motorsport is dangerous, and was even more so in the Fifties, but the number of fatalities and serious injuries mentioned in this book is sobering. The Fun stopped, suddenly and brutally, on countless strips for too many youngsters as they looked to shut down the guy (or gal) in the next lane. Safety precautions were laughably inadequate; Johns describes how the burns Don Garlits sustained in 1959 “highlighted the need for more protection than a T Shirt and leather jacket. At first, stiff fire suits appeared, consisting of cotton soaked in baking soda. . . . The benefit [of Zoomie headers] . . . was offset by poisonous exhaust gases containing paralysing nitric acid vapour, directed at the driver, who could not breathe.” As speeds increased, so, thankfully, did safety. But never, ever underestimate the speeds involved. Even casual fans know that a modern Top Fueller has more horsepower than the first five rows combined of a Grand Prix, and that in the time Max Verstappen’s Red Bull takes to hit 125 mph, the fueller will have already gone 200 mph faster. And consider this: sixty years ago, when a Jaguar XK-E’s 15 second @ 95 mph quarter made it king of the hill, Flamin’ Frank Pedrogon’s Fiat Topolino Coupe was running the quarter in 8.0 seconds, at 200 mph. And why “Flamin”? Frank’s party trick was to set his wheels on fire for the first 300 feet!

Just buy this book —it’s a delight, and if you’re not tempted to visit your local strip this Spring, then you need to seek medical advice.

Copyright John Aston, 2026 (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter