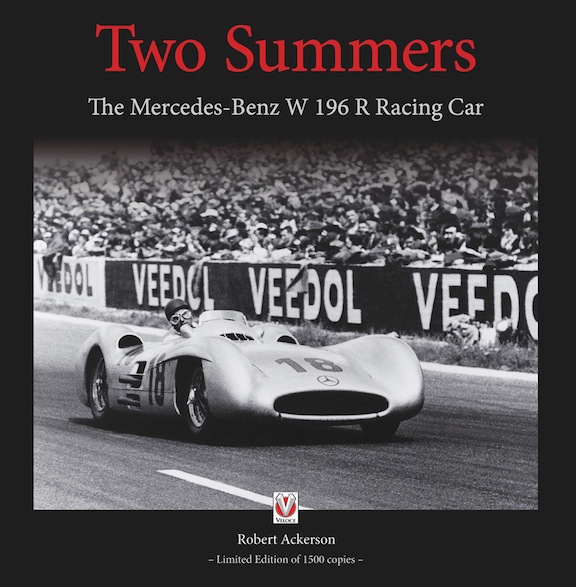

Two Summers: The Mercedes-Benz W 196 R Racing Car

“It was magnificently streamlined and from the very first tests I was sure that I had in my hands the perfect car, the sensational machine that drivers dream about all their lives.”

—Fangio

Why “two summers”? Because in 1954 Mercedes won 4 out of 6 GPs, and 5 out of 6 in 1955, four of the latter won by Fangio who could have made it 5 for 5 if he hadn’t thrown teammate Moss a bone and let him win his home GP. Perfectly good reasons why these years are especially important to M-B, and perfectly good reasons to write a book about them. Except . . . you won’t find a statement as succinct as the above anywhere in the book, which is odd when you consider that a book this expensive would want to give prospective buyers all the reasons in the world to justify its existence.

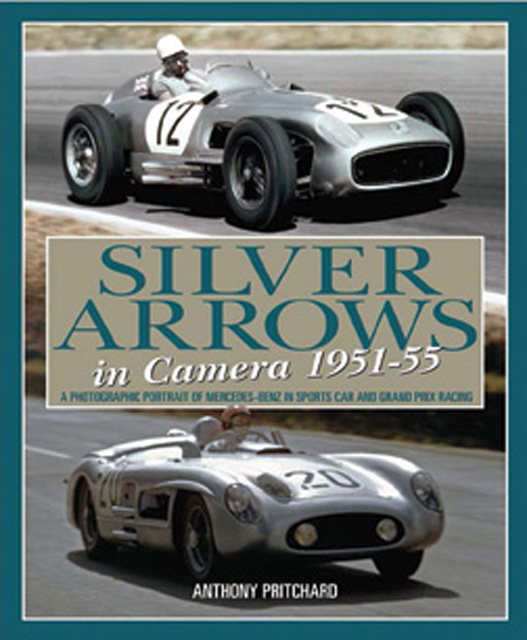

But perhaps the book is written for those old hands who can be expected to already know such background, except . . . those readers would have a well-thumbed copy of Anthony Pritchard’s superlative Silver Arrows in Camera, 1951–55 on the shelf. And they, more than anyone, would need convincing that this new book is worth their time and money.

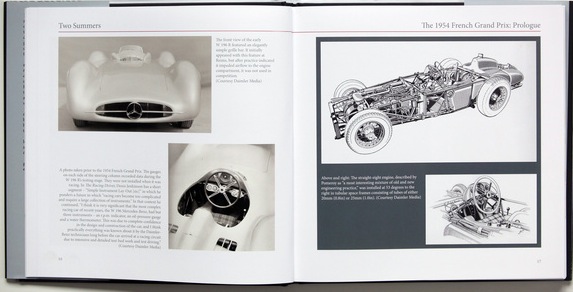

Ackerson does offer an Introduction but its sole purpose is to pay homage to the European and American motor racing journalists of the 1950s whose names we know and love, and whom the author read as a young man. With that in mind, the first sentence on the dust jacket, which is usually not written by the author, offers a clue to the book. It says it “offers a fresh, revealing and highly personal window into the culture of Grand Prix racing as it was during the 1954 and 1955 championships.” A provisional yes to that: at its core the book is a stringing-together of period English-language race reports and quotes of auto/biographies by the principals, so, if you did not read these sources in their day, or have no access to or knowledge of them now, then this book will be fresh and revealing and, not least, convenient.

Those period race reports really are marked by a certain candor that is no longer found, largely because the relationship between the drivers/teams and the reporter/s has changed. They were also written in colorful, gripping prose because they had to paint a picture for the radio listener or newspaper/magazine reader who, in those pre-TV days, could not see what the reporter saw.

The dust jacket further alludes to “carefully-crafted observations and conclusions,” and this raises questions. The very methodology of (merely) excerpting a multitude of sources (which are numbered in the text and then presented as footnotes at the end of each chapter) is not the same as independent assessment or critical weighing and reconciliation of conflicting data points. This is certainly achievable, and practiced every day in the academic world, but makes for headache-inducing reading and would be out of place in a “mass market” book (insofar as a print run limited to 1500 copies can be considered that).

What Ackerson does achieve, and which clearly is the point of the book, is to give compelling, lively evidence of the W 196 R’s dominance and, specifically, that Argentine five-time F1 world champion Juan Manuel Fangio deserves an exalted place in the pantheon of drivers. The book covers the 12 races in those two years that counted towards the world championship (one that didn’t is appended, the 1954 Berlin GP).

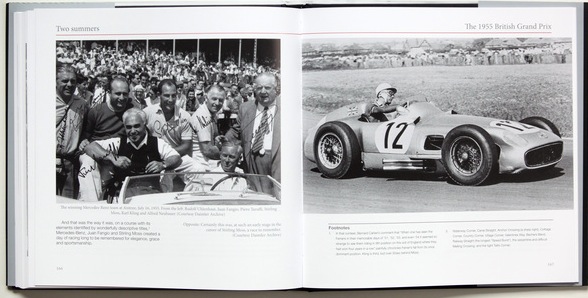

Most races are preceded by a Prologue offering historical background in the form of extensively captioned photos. But here too there is no real independent interpretation but merely/mostly a verbalization of what the photo shows. If you have the Pritchard book you’d find many of the same photos used there (often larger, better-reproduced, and some in color) and comparing their captions shows that they convey rather more detail. All the photos here are from the Daimler Archives and it is possible that there is the odd photo that hasn’t been published before. Be that as it may, the illustrations are plentiful and support and amplify the text in a thorough and suitable way so if you are new to the topic, the book does offer a well-rounded overview.

The amount of typesetting glitches (not just typos but altogether missing words etc.) is too large to escape comment and there really is no excuse for someone who is said to be a “life-long student of M-B history” to spell German names wrong (e.g. Hans Herrmann but Hermann Lang, inconsistent throughout; the former, to add insult to injury, missing entirely from the rather spotty Index) or why a photo (p. 111) is captioned as Moss when it should be Fangio who is shown only two pages later in the same car—particularly ironic in that era of open-faced helmets. For most races, starting grid and/or finishing order are listed in tabular form, albeit inconsistently, and without starting number which could have prevented the above mistake. (Also see comments, below.)

If it is the flavor of the era you want, the actual slicing and dicing on the track, rather than an in-depth treatment of the technical bits, this could be the right book. It is a companion volume to Ackerson’s previous book Return to Glory that focused on the 300 SL and together they do make a nice pair. Return was published in 2013, which happened to also be the year in which an ex-Fangio W 196 R (chassis 00006/54) fetched the then highest-ever auction price: $29,650,095. Meaning, chances are you won’t see one in the wild and a book is the next best thing—or, in the US, a visit to the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Museum where chassis #9 has been on display since 1965.

Copyright 2016 (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter

Re. the Moss / Fangio photos pp. 111, 113:

This is not nitpicking, as we will demonstrate here. The photos captioned as M. and F. show the same car, #2, the one F. started and finished in, as M. did in #6. In other words, M had no reason to be switched to F’s car so there should be no photo with his name in car #2, ergo we rule this a mistake either in captioning or photo selection.

But drivers DID change cars, and an example is the case of a car shown on the page between the above. Here the author shows 2 views of car #8, one captioned Herrmann and the other Kling. H. did start in #8, but K. in #4 so what’s he doing in the #8 car? K retired on lap 2 with an undriveable car and was assigned as a relief driver to H’s #8 car. Ergo the same car #8 at the same race with 2 different drivers–counter to the starting grid order–is plausible. But, we’re still not impressed…an author who cared about his reader would have added, in the name of user-friendliness if nothing else, that #8 also retired undriveable with engine probs which is why the reader should not be confused by finding H. and K. as race finishers–on Moss’ #6 car which they took to 4th! This is not spelled out in the caption or the text and would only become apparent when you try to puzzle out the table showing the finishing order.

Why, you wonder, did 2 drivers get shuffled into Moss’ car and none into Fangio’s? Because F was [a] multiple world champion and would have had a fit if someone disturbed his flow, and [b] as a native son he was used to the brutally hot weather that felled others during the Argentine GP and didn’t need a relief driver. Moss, in fact, had been–temporarily–pulled out of his own car during the race for heat exhaustion. If M had crashed his car then, all 3 (M, H, and K) would have been out of a drive. Incidentally, even the sainted A. Pritchard got this wrong in his data table (p.209) listing the retired car #8 as the finisher instead of Moss’ #6, but his photo captions have it correct.