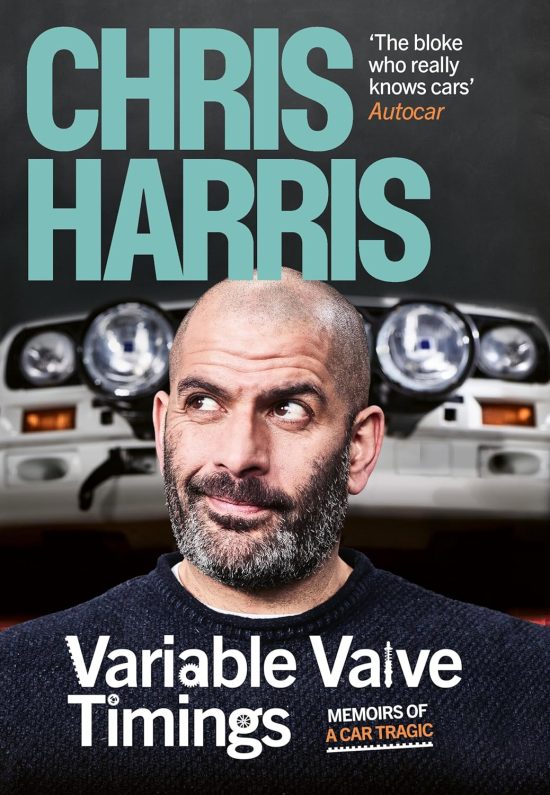

Variable Valve Timings: Memoirs of a Car Tragic

by Chris Harris

by Chris Harris

“I’m a shy extrovert. In my comfort zone I’m the Japanese knotweed of the conversation—an ever-present menace you’d rather be rid of. Away from that place I’m awkward and quiet.”

It started with a fist. If Top Gear presenter Jeremy Clarkson hadn’t punched BBC colleague Oisin Tymon for having failed to provide him with a steak dinner, hardly anyone would have heard of Chris James Harris.

Before the BBC sacked Clarkson, Harris (b. 1975) was known only to guys who recite Porsche model numbers by heart and who spend too much time watching cars being driven sideways on YouTube. Clarkson and his chums went on to create The Grand Tour on Amazon, the show that was almost indistinguishable from Top Gear except for its massively increased budget. And that left the BBC with a problem: Top Gear was the BBC’s golden goose, but could it survive without the alchemy of Clarkson, May, and Hammond? The answer was a reboot, with the same format but a new bunch of presenters, one of whom was Chris Harris.

This is a relatively short book and, although I had assumed it was an autobiography, it’s nothing of the sort. The publisher calls it a memoir, which explains why I’m still not much wiser about what makes Harris tick. But as a compulsive consumer of motoring media for decades, I am not the target reader, because the rich pickings are the Top Gear audience, a vast demographic much wider than the traditional car guy. Thanks to Clarkson and his erstwhile schoolfriend Andy Wilman, who originally created the template for the show, Top Gear is still the must-see car program for viewers who aren’t very interested in cars. Clever, huh?

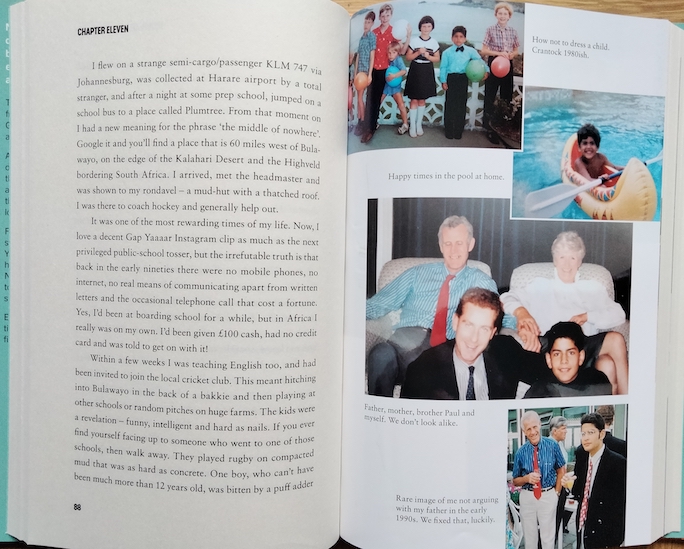

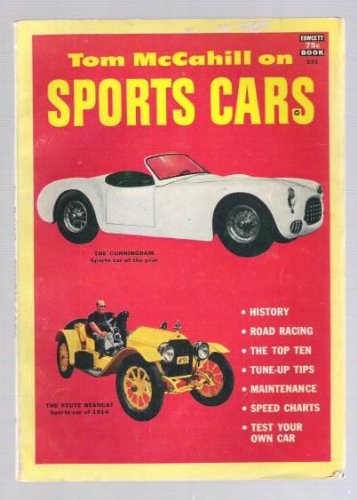

Enough of the overture—what is the book about, and how good a read is it? The answer to the first question is that it’s the story of the mixed-race kid who was adopted by middle class, well-off parents in Bristol. The kid was embraced by a loving family but he didn’t quite fit—his attention span was short, he loved school but had an aversion to learning, and he knew he was different. “My brain didn’t work quite the way it was supposed to.” The first hint of salvation came to him as a six-year-old, when he immersed himself in the data section of What Car magazine. “I buried my head in the back pages . . . blissfully unaware that it was possibly the most important moment in my life.”

Harris’ life became defined by an almost deranged obsession with cars, manifested by consuming print, TV, and film content about cars to the virtual exclusion of all else. And then he made a career out of “viewing the outside world through the prism of cars.” Isn’t that “outside” significant?

Harris’ life became defined by an almost deranged obsession with cars, manifested by consuming print, TV, and film content about cars to the virtual exclusion of all else. And then he made a career out of “viewing the outside world through the prism of cars.” Isn’t that “outside” significant?

I can identify with the man who shared my own preoccupation with CAR magazine in its Eighties’ pomp. Like Harris, I savored the prose of the journalistic greats like Setright, Green, Nichols, Fraser, Robinson, and Bulgin as if it were a religious tract, delivered from on high by the prophets of a new religion. Harris is generous in his praise of the “Australian invasion” but, although four are included in the list above he doesn’t mention the Ur Strine*, Doug Blain. His blisteringly iconoclastic prose left no sacred cow unprodded, no manufacturer unprovoked in CAR’s glorious early years, when it became the template for the new automotive journalism. But with a debt owed to David E. Davis and Brock Yates.

Harris was destined to become a car journalist, and reading about his unremitting fervor for the subject it was surely the only show in town? He’d tried teaching abroad and he’d side- hustled buying and selling cars but year zero was when he became the work experience** brat at Autocar, almost hysterical with excitement at sharing an office with heroes Steve Cropley, Colin Goodwin, and road tester Steve Sutcliffe.

Autocar was his salvation and despite the (unwanted) fame and (deserved) fortune which is the legacy of his TV career, he admits he was never happier than during the time he spent in the simpler era of print media. His account of his ascent through the motoring media is breathless and absorbing. Having explored the gentle foothills of Autocar he explored the terra incognita of Drivers Republic (the web based, apostrophe-free “drivers’ community” which sank without trace in 2009) before returning to the safer, but ultimately unfulfilling terrain of Evo. He knew he could talk to camera without tripping over his shoes and his smart move was then to establish a niche in the brave new world of YouTube. His authentic car nerd schtick worked well on video, resonating with a big enough community for Harris to become a name you’d hear at Cars and Coffee mornings or in race circuit paddocks. Like his journalist predecessors Paul Frère, Roger Bell and Evo friend Richard Meaden, Harris proved to be a very capable race driver.

Big photo: can you spot Master Harris? He gives a clue: “We don’t look alike.”

There is plenty of car stuff here, and if none of it surprises, Harris’s effervescent tales of beloved French hot hatches and his first Porsche, a (then) bargain basement 911 CS, convey an almost childlike joy. Harris never let fiscal reality spoil his fun—the typical UK car journalist might aspire to an Elise or a BMW M3, but even the young Harris was able to boast of exotica such as his Porsche 993GT2 and Ferrari 512 TR. This is the guy who confesses “Come summer we didn’t have any money at all, and personally I was living in a fantasy land . . . to compound the utter madness I bought a used Ferrari 612 Scaglietti on the skinniest finance deal imaginable.” The typical Brit car guy might have heard or read these tales already, but Harris’s revelations about 1990s car journalism add real grit to the oyster by exposing a trade that was both grubby and corrupt. He describes some of his fellow journalists thus: “A bigger swamp of talentless liggers you couldn’t hope to meet . . . in 1998 the UK motoring journalist community was mostly a cesspit.” Or how about the revelation of what the BMW GB comms boss had said of (mixed race, remember?) Harris: “His sort don’t know how to treat women anyway.”

It may surprise, even disappoint some readers that 80% of the book isn’t about Harris’ Top Gear experience. But if you’ve watched the show (and who hasn’t?) you already know most of the story anyway. But there’s some gossip to savor, not least one-time anchorman Chris Evans’ incompatibility with the author, epitomized by Evans’ comment about Caterhams that “he didn’t get them at all.” As Harris says,“this was like a chef saying they can’t abide an omelette—it completely undermines their credentials.” I drove Caterhams for 20 years and I can only agree. And yes, I’ve been harboring doubts about Chris Evans for years; who can trust a guy with a “White Collection” of Ferraris when it is an inviolable truth that the only car that ever looked good in white was the Toyota 2000 GT? But a Ferrari 250GT SWB, in white? Get outta here . . .

Harris found a kindred spirit in fellow Porsche-loving co-presenter Matt LeBlanc (a Friend indeed? Ouch.) and in his last two co-presenters, Paddy McGuinness (ubiquitous on British TV) and Freddie Flintoff (former international cricketer and house-trained bad boy). The show is now on hold—Flintoff retired hurt after rolling a Morgan Super 3 but I’m sure we haven’t seen the last of the little guy who self-deprecatingly calls himself “harrismonkey” on Instagram. Jeez, there’s a thesis-worth to unpack, right there.

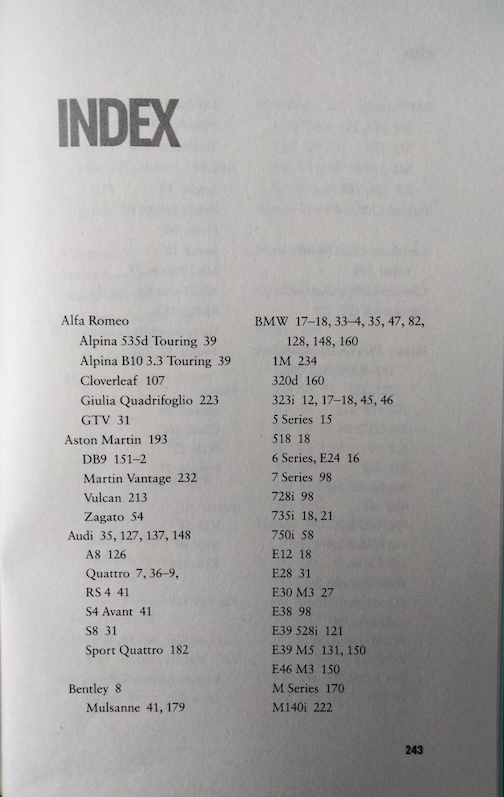

So how good a read is it? It was enjoyable, but it’s not a book that will reveal any more secrets on a second reading. Harris lacks LJK Setright’s erudition and can’t play the zeitgeist savvy hipster like Russell Bulgin, but he writes in an endearingly conversational style, making the book a fast, easy read. Damning with faint praise? Perhaps, but you can’t help warming to Harris. If his podcasts are anything to go by, his public persona can be near insufferable, but this book reveals a more nuanced character. He clearly isn’t the spoiled rich brat some imagined, his work ethic is extraordinary, and his insatiable love of cars is endearing. In a book punctuated by personalities—fellow journalists, big beasts in the media and car industry—who else would have included only car models in the Index? His step-parents, his petrolhead mother especially, sound wonderful but we learn very little more about his family. He mentions his half-brother just twice, and there’s the most fleeting reference to his kids (the C, X, H in the dedication?) but of home and partner(s)? Nada—but it’s memoir, not autobiography, remember?

STOP PRESS – The BBC announced on 22 November 2023 that Top Gear has been taken off the air “for the foreseeable future.” Chris Harris fans will still be able to find him on his “Collecting Cars” channel on YouTube.

*Strine – period English slang for Australian

** Work Experience – equivalent to “intern”

Copyright John Aston, 2023 (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter