Superbears—The Story of Hesketh Racing

by James Page

by James Page

“Where (Hesketh) score is that they are all happy and friendly while going about a serious occupation, while the other teams go around poker faced and miserable, doing the same job . . . less successfully”

—Ian Phillips, “Autosport”

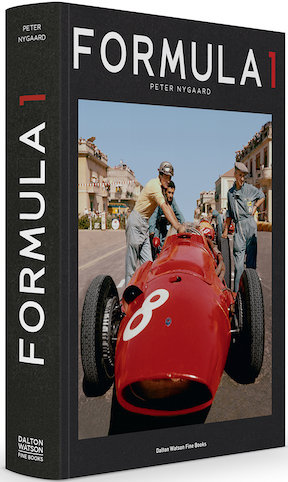

Thanks to an unprecedented heatwave, most Britons had taken leave of their senses in July 1976. Laborers on the Humber Bridge downed tools after being attacked by hordes of angry ladybirds, buxom streakers kept the tabloid press well-endowed with cheesy headlines and a riot took place at Brands Hatch. The people’s hero, James Hunt, had been denied a restart after an accident involving arch rival Niki Lauda’s Ferrari. Soccer fans were notoriously badly behaved in the Seventies but motor racing fans had always been relatively genteel, and bad behavior was unknown at the British Grand Prix. So what was it that triggered the angry shouts (including from this reviewer), the mass chanting, and the fusillades of beer cans? James Page’s insightful book helps to answer that question—James Hunt was driving a McLaren at Brands, but the seeds of the crowd’s loyalty were sown during the three previous seasons, when Hunt drove for Hesketh.

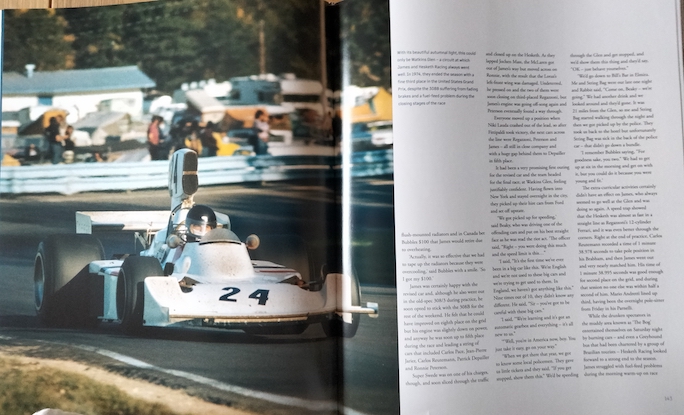

Porter Press has produced a big (12 ½” x 10 ½”), boldly designed book; the combination of Page’s prose and the wealth of period pictures and ephemera help to explain the phenomenon of the private race team that took on the motor racing establishment. Lord Alexander Fermor-Hesketh (aka “Le Patron”) and his friend Antony “Bubbles” Horsley’s racing odyssey had started in the hyper-competitive arena of Formula 3 and, after a shaky start, James Hunt was recruited in 1972. As Horsley puts it, “. . . (Hunt) was quite fiery—he’d punched Dave Morgan at Crystal Palace—but he seemed to be quick and competitive.” But there was no real sign of Hunt’s ultimate potential until his extraordinary performance at a Formula 2 race at Oulton Park in September 1972. I was at that meeting and I can remember the buzz as the crowd became aware that James Hunt was the real deal, as he harried Niki Lauda’s newer March 722 to finish third. In Bubbles Horsley’s words, “Without that race, nobody would have heard of us.” And the rest is history, with the first F1 points scored in 1973, a debut F1 victory in the Daily Express International Trophy in 1974 and a first (and only) Grand Prix win at Zandvoort in 1975. But, within three years of that triumph, the team was clinically dead and its life support machine was turned off mid-season in 1978.

This book doesn’t feature the forensic degree of detail some recent driver-and-team biographies have boasted, but it does pack a wealth of material, much of it new to me, into its 264 pages.

Author Page has had access to many primary sources of research, and Lord Hesketh’s scrapbooks bear witness to the young peer’s Tigger-ish enthusiasm. The Hesketh team were notorious for their nicknames, merry japes, surreal rituals (such as the prayer to “The Great Chicken in the Sky”) but the silliness actually camoflaged a serious race team. That said, the passage of fifty years has offered me different perspectives since the days when my Riley 1300 sported the brilliantly designed Hesketh Bear, whose adventures are also chronicled.

Alexander Hesketh had an extraordinarily privileged upbringing but was touched by tragedy when he lost his father, meaning that he became the 3rd Baron Hesketh at four and a half years old. Absurd though it sounds, such is the essence of the British aristocracy, as portrayed in Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited. One thinks of Sebastian Flyte, with Aloysius (Flyte’s teddy bear) in a cameo role as team mascot.

As a young man, Lord Hesketh enjoyed the fruits of his wealth, exemplified by the team’s sheer flamboyance and self-indulgence, including the travel by Rolls-Royce, private jet, and team helicopter. Naturally there’s a superyacht. This was against the background of a country beset by industrial unrest, inflation and unemployment, and I am tempted also to question the then popular narrative that the team was somehow shaking the establishment. The book now makes me wonder whether the windmills at which Hesketh was tilting might have been largely imaginary, just convenient props to boost the team’s contrived eccentricity.

Remember that Formula One in the 1970s was almost unregulated, compared to the stifling conformity of the sport in 2023. There was no virtual cartel of vested interests, no nonsense about new teams having to lodge huge financial guarantees but, instead, a laissez faire regime that applied the softest of touches. Anybody who could get hold of a Cosworth DFV and a chassis in which to bolt it could turn up to a Grand Prix and have a go at qualifying. Hesketh might have had a side order of whimsy, more champagne and hotter girls, but in essence were they really so very different to those arch disrupters at March or more doggedly ambitious than Frank Williams?

But, as Page emphasizes, the Hesketh team had a secret weapon. He was called James Hunt but was christened Superstar by team members. The author describes how this confident and hyper-competitive former public schoolboy* firstly thrived in the stubby white March 731, and then positively flew in the gorgeous, red white and blue striped Hesketh 308. It was a meteoric rise to fame and, testament to just how serious Hesketh was now being taken, is the curious story of how Enzo Ferrari invited them to Maranello in 1974 to discuss the prospect of a Hesketh–Ferrari. Alexander is quoted as saying, “The Commendatore pretended not to speak English. That was untrue, but when you go and see the Sun King and he says this is how it’s done, then that’s how it is done.” This book has a wealth of tales like this, some little more than rumors in period, and others completely unknown until now. The anecdotes are fabulous too, but they are not all flattering—Bubbles Horsley recalls how Alexander was once challenged for smoking in the pits: “He’d say ‘it’s my car’ and get his lighter out and run it down the side of the car—whether it was being fuelled or not.” I wonder if the droit de seigneur schtick was claimed as well?

The detailed appendices reveal that Hesketh only ever made eleven 308 chassis which was a surprise, if not as much as the fact that a total of 14 drivers raced them. But perhaps rightly, we only really remember the one, the golden boy with the posh accent, the quick temper, and the gorgeous girlfriends.

James Page is a respected journalist with a background in motorsport and classic car reportage and, with one small caveat, he has done justice to a subject long overdue for a serious biography. He chronicles the team’s story chronologically, rightly concentrating on the glory years 1973–5, but not neglecting to cover the fate of the team after Le Patron effectively ran out of money, leaving Hunt free to take Fittipaldi’s former seat at McLaren. The author chronicles how the once iconoclastic Hesketh then became just another F1 team, renting out drives to relative no-hopers like Harald Ertl and Rupert Keegan. The caveat? I enjoyed the wealth of anecdote and recollection from team and family members but I would have liked more contributions from the wider F1 community. Hunt and designer Harvey Postlethwaite (“The Doc”) both died young but the thoughts of some more of the many survivors of the era would have added context. People like the outspoken Alistair Caldwell of McLaren, and rival drivers such as John Watson and Jackie Oliver, neither noted for their reticence. And Freddy Hunt perhaps, James’s son and Alexander’s godson. I wonder how should we react to the claim made by Freddy in a 2019 podcast that he had seen Lord Hesketh just once since his father’s funeral in 1993?

Page’s book is testament to how the Hesketh saga, though brief, has enjoyed an extraordinarily long afterlife, thanks to the Hesketh Bear and the legacy of James Hunt. The trademark Bear, in both original and flying format, is still sported by many motorsport fans, including by some whose parents weren’t even born during Hesketh’s days in the Seventies’ sun. Hunt continues to be lionized as the nonconformist racer, not least by Kimi Raikkonen (born in 1979), who sported a James Hunt replica helmet in practice for the 2012 Monaco Grand Prix. This book is long overdue and deserves a place in the library of anybody who enjoyed the anarchic world of early Seventies’ Grand Prix racing as much as I did.

James Page and Porter Press have created a hugely enjoyable tribute to a lost era. Yes, Hesketh Racing was ultimately no more than a rich kid’s indulgence, but read the text, drink in those immensely evocative pictures, and then tell me you don’t wish you’d been a part of it . . .

- * The British public school is an oxymoron, being equivalent to an exclusive private school in the USA.

Copyright John Aston, 2023 (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter