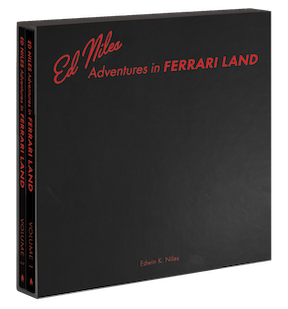

Adventures in Ferrari Land

by Edwin K. Niles

by Edwin K. Niles

“I think that a word or two about my motivation might be appropriate. Yes, I always tried to make a profit on each car. I usually succeeded, but not always. I took a loss on a few. Even when I made a profit, if I counted my labor bringing a car up to saleable standards, I would have been working for about two cents per hour!

No, it was all about the differences. All Ferraris were different from other makes, and each Ferrari was different from its sisters.”

For anyone who has been immersed in Ferrari lore, enthusiasm, or ownership for any significant length of time since the early 1960s, the name Ed Niles (1924–2021) will be a familiar one. He didn’t so much enter the Ferrari “scene” on the West Coast—because there really wasn’t one—as make it, and not by dint of any great master plan but simply by following someone else’s suggestion and finding it worked. A freshly minted lawyer and newly married, the Nileses found themselves invited to join his wife’s parents on a month-long trip to Europe in 1959. So why not bring back a used car and flip it to defray the costs?

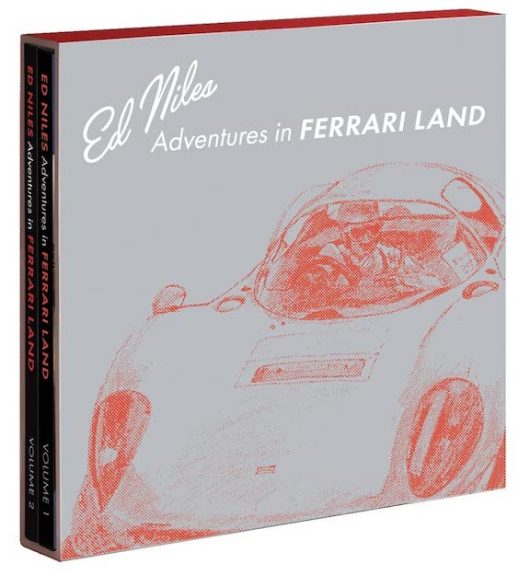

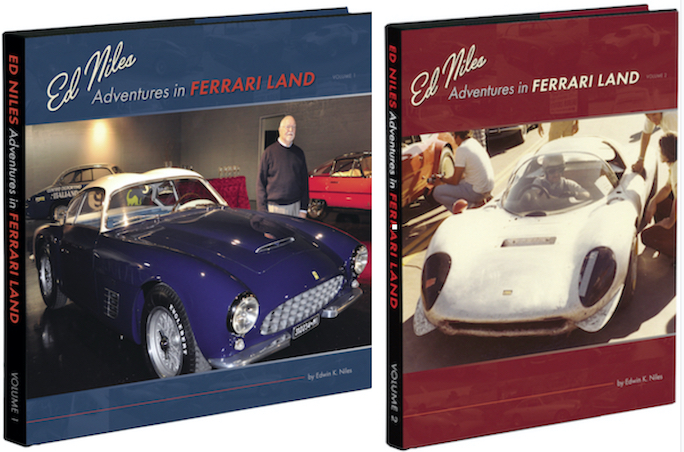

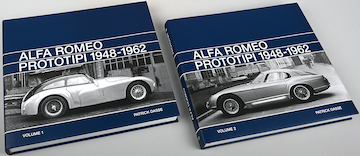

Would you believe the dapper fellow on the cover of vol. 1 is 90 years old? He was 95 when he wrote this book and died soon after, in August 2021. The lesson here? If you have a book in you, don’t dawdle. Surely you’ve observed that vols 1 and 2 are not the same width. So how do their spines stay flush in a common slipcase? Engineering!

And so it began, with a used 250 GT Europa found in Rome on the last day of that vacation with the help of a local whom Niles had first met as an exchange student staying with his in-laws, Roberto Goldoni. That first purchase was not made because Niles divined Ferraris were the future or that that particular car was special in any way but simply because he ran out of time and it fit his budget (well, his bank loan’s budget).

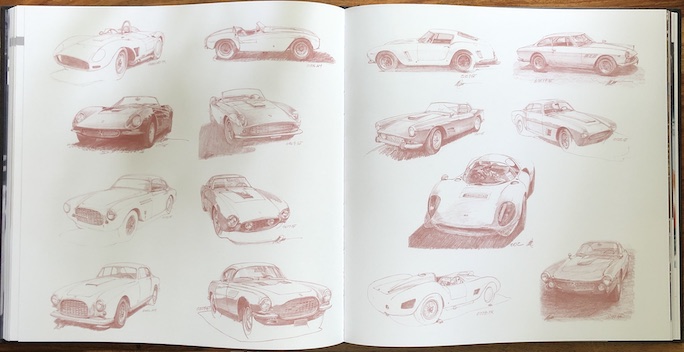

Illustrator Chuck Queener was still a student at Art Center School of Design when he met Niles in the late 1960s who was then president of the Ferrari Owners Club, a gig in which Queener would succeed him

He made a quick and decent profit on the first flip, having fun driving a cool Ferrari in the meantime. It worked that first time, and it would work a hundred times more. Having Goldoni as a trusted local resource was a tremendous asset in that Niles could buy cars sight unseen, and the two would share the profits. Over the course of the next six decades his lawyering, which he practiced until near the end of his life, would become merely a sideline to his Ferrari-brokering. In the early days when there was no established knowledge base in regards to service, let alone factory support it was the steady stream of his used, often very used cars that made it feasible for auto techs to specialize in Ferraris, for owners to form clubs, and all around shape the infrastructure of . . . Ferrari Land.

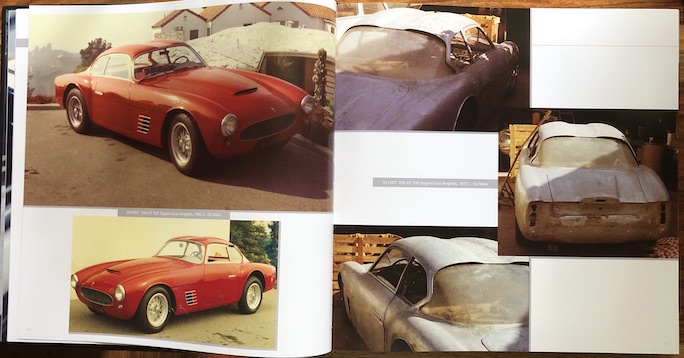

0515GT in 1965 when Niles bought it. One look and you know the double bubble roof spells Zagato aka ultra desirable. Except, back then, as hard as it is to believe, no one—including Niles who started out buying cars sight unseen simply based on what his scout in Italy told him about them—seems to have cared, or recognized it or assigned any special significance to it. What makes this even more puzzling is that this rare car returned to Niles six times between 1960 and 1986 to be flipped.

Adventures In Ferrari Land is thus an automotive memoir. Books of this type are becoming more popular, and thankfully so. Without people like Niles committing the time and effort to tell their stories much history will be lost, not to mention the recall of minutia a first-person account can draw on that would be difficult to reconstruct by a later biographer.

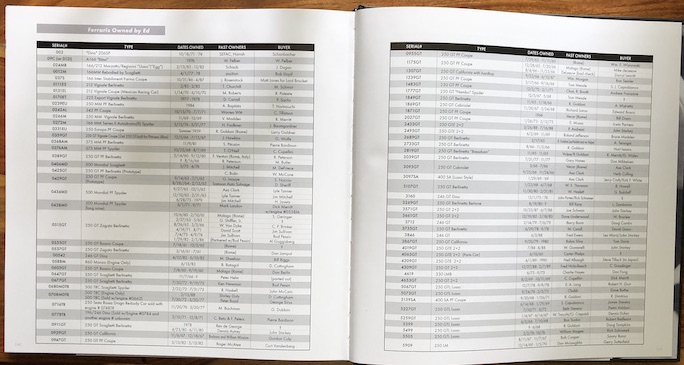

The first of the two volumes is a chronological account by date of acquisition of 51 of the cars (a table at the end of each volume lists all of Niles’s ca. 120 cars in order of serial number, below) accompanied by sidebars about or by people that play recurring roles in the story. Volume 2 contains reprints of articles Niles wrote for Ferrari club magazines and other publications, along with images of assorted ephemera.

There is no explanation of how the cars featured in Volume 1 were chosen to be included. The reviewer suspects that they were simply Ed’s favorites or perhaps the ones about which he had the clearest recollection. It is impossible for a contemporary reader who has an awareness not just of the Ferrari market but also the historic significance of some of Niles’s cars (prototypes, one-offs, race cars) not to be puzzled by the utter lack of knowledge or even interest back in the day in such matters as provenance, authenticity, or coachwork. Ferraris are of course not alone in this. Maybe it’s the lawyer in Niles that prompted him to keep meticulous records of the cars he traded (some several times).

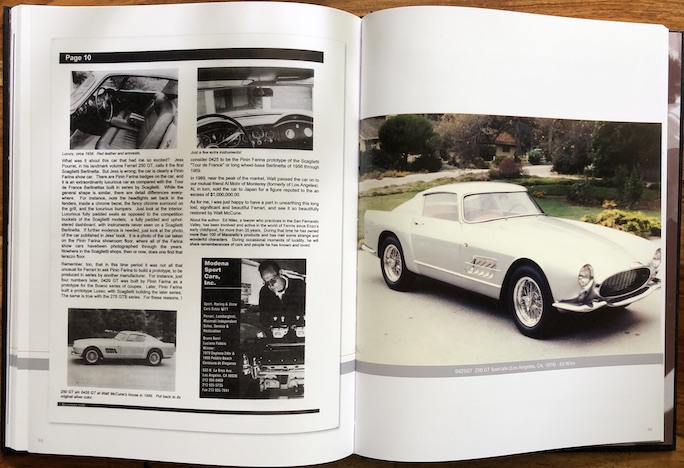

Vol. 2 contains reprints of various columns and such that Niles wrote. To a Ferrari enthusiast who actually owns the original publications, this would not be very tempting except that in quite a number of instances the old articles are here augmented by photos of the subject matter at a different time in life. Here the article about #0425GT is from 1996 and the big color photo from 1974.

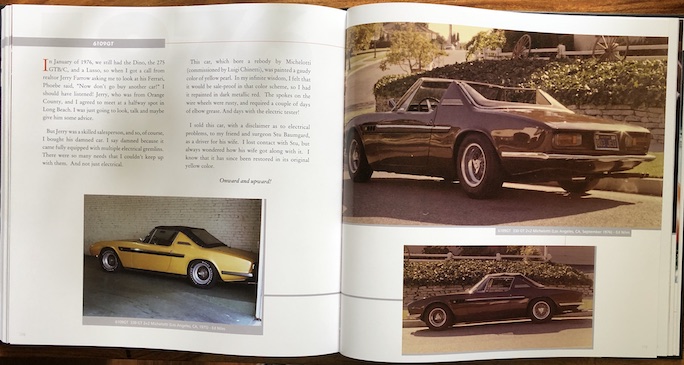

6109GT. This car illustrates a common theme for Niles: if it was unusual he wanted to have it, even if he didn’t like it (this is a rebody by Michelotti), just to be able to expand his experience.

After selling his last Ferrari, it took a while for Niles to perceive a void in his life—so he bought one last one, a keeper, not to drive but just to know it’s parked in the garage. This (relatively) humble 328GTS is not included in his list of cars owned, although it is prominently featured at the end of Volume 1.

Niles was known to be self-effacing and his comments throughout demonstrate this, beginning with his Prologue wherein he warns the reader, “Just remember, I’m 95 years old and no longer have any of my files, so there might be a few errors. I do have a photographic memory but I may run out of film. I used to have hard muscles and soft arteries, but they seem to have traded places!” This and his innate honesty and decency are probably the reasons he formed such firm and lasting friendships with the aristocracy, if not royalty, of “Ferrari Land.” Most enthusiast readers will recognize names like Phil Hill and Bruce Meyer, but Ed was also close to less generally well known but serious players like Pierre Bardinon, Steve Tillack, Marcel Massini, Chuck Queener, Sir Anthony Bamford and others either as friends, clients, or more typically, both.

An interesting section deals with the parallel rise of Niles’s and Tillack’s profiles in the Ferrari stratosphere. For many years now Tillack has been a premier restorer of classic automobiles—but did you know this erstwhile car stereo installer was once the face of a Pioneer ad campaign?

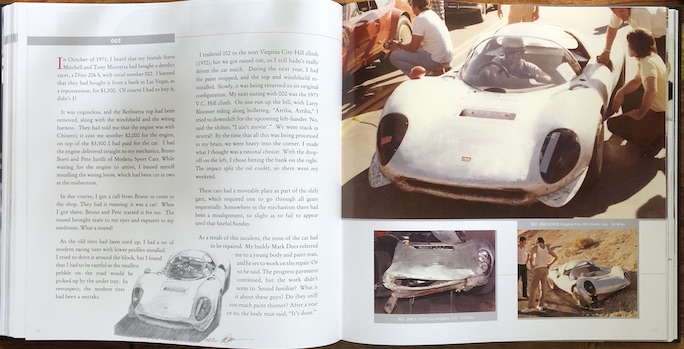

Dino 206 S, #002. Bought in 1971 and fixed up, then trailered to the 1972 Virginia City hill climb—where Niles crashed it into the bank to avoid an even bigger accident.

There was more to Ed’s Ferrari enthusiasm than the cars and the people, and the book amply expresses these interests. He was an early member of both the Ferrari Club of America (charter member) and the Ferrari Owners Club (virtually a founding member). The FCA became recognized by the Ferrari factory and the FOC is national in scope but California-centric. He was a prolific contributor to the publications of those clubs as well as to Ferrari Market Letter, the go-to place for advertising all things Ferrari both on paper and online, founded by Ed’s late friend Gerald Roush. Ed also writes about some of his favorite places: Italy, France, and of course his beloved Southern California. His Ferrari involvement took him to places and events like Pebble Beach, Mille Miglia Storica, Donington Estate (Bamford), Mas du Clos (Bardinon) and Maranello, as well as many other venues, not as a spectator but as a respected participant. And his chapter on meeting and wooing his second wife Phoebe is charming. The book provides a glimpse into the SoCal car scene in the early ‘60s–‘70s as well as we read about cars being used as daily drivers around the Hollywood Hills, Malibu and other swank neighborhoods, cars that are now mostly cooped up in climate-controlled Garagemahals with elaborate security systems and shipped from venue to venue.

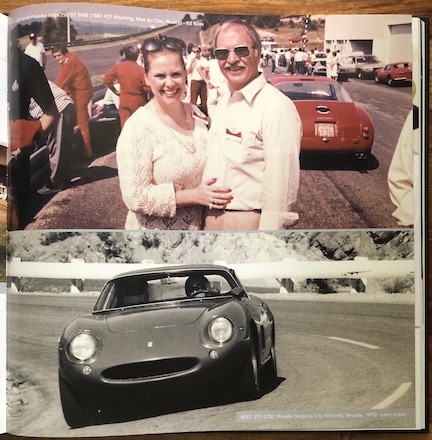

Ed Niles with his second wife Phoebe. The top photo is from 1981 and the bottom one from 1975, barely a year after they married—and that’s Phoebe at the wheel of a 275 GTB/C leaning into the turn and setting a better time than Ed at a Virginia City hill climb. She would claim one of Ed’s cars as her own, a Dino, and drove it happily—until he flipped that too.

Ed Niles has done a service to the denizens of Ferrari Land by writing this book. He certainly didn’t need to do it at the stage of life at which he wrote it. The reviewer enjoyed his conversational prose, his retro lexicon (describing his first glimpse of a “great looking young babe”—whom he would marry—is a favorite) and his absolute lack of pretense.

Much of the photography is decidedly snapshot quality but it complements the authenticity of Niles’s writing style. Since many are from his own and others’ personal archives, it’s likely that many are seen here for the first time in print. There are a few photographs, mostly of restored cars, that appear to have been done professionally.

This book is a bargain for any Ferrari enthusiast who is interested in the history of Ferraris of the 1950s and ‘60s, particularly how they shaped the life of one man.

Also available in a leather-bound Collector’s Edition (right), ISBN 9781642340853, $275.

Also available in a leather-bound Collector’s Edition (right), ISBN 9781642340853, $275.

Copyright 2022, Jack Brewer (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter

I had the privilege of selling Ed his last Ferrari. It’s the ’86 328 that he is pictured with in the book.