Test Pilots: The Story of British Test Flying 1903–1984

by Don Middleton

by Don Middleton

“The public image of the test pilot has changed considerably in the short history of aviation. In the 1930s, Hollywood flying epics suggested a daredevil, hell-raising cowboy type with an equal interest in flying, women and wine – no doubt there were a few around. In the 1950s and 1960s the image changed to the gladiatorial phase, slightly more convincing, of supermen facing fearful odds in attempting to ‘break through the sound barrier’ as the press were apt to describe transonic flight. The truth is more prosaic. From the beginning of powered flight, test pilots have predominantly been thoughtful, highly skilled men with analytical minds and in many cases an extensive knowledge of aeronautical engineering. The test pilot of today is a similar but much more highly trained individual, with a sound scientific knowledge to take full advantage of the very complex modern technology which is at his command.”

The above is the cover blurb of this book that was written by the author in 1985. In the forty years since then test flying has changed out of all recognition. The advent of sophisticated Computer Aided Design, advanced construction materials, and realistic flight simulators have all made the role of the test pilot very different. The reduction in aircraft manufacturers and increased lifespan of models also has an impact. The venerable Boeing B-52 has a project lifespan of 100 years from the basic design, with the Hercules C130 not far behind. Both of these happen to fall into the time span this book covers.

As the title states this is the story of British Test Flying 1903–1984, other countries, particularly the US, do not get much of a look in. As a foretaste, at the very beginning the author quotes:

As the title states this is the story of British Test Flying 1903–1984, other countries, particularly the US, do not get much of a look in. As a foretaste, at the very beginning the author quotes:

“A superior pilot is a man who uses his superior judgement to avoid the use of his superior skill.”

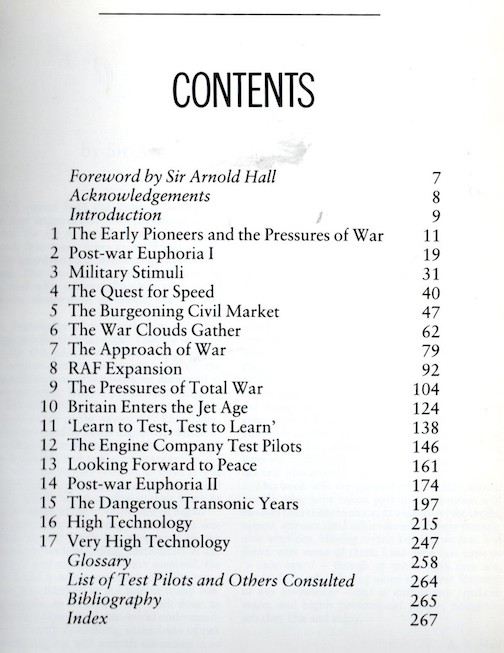

In actual fact the book covers quite a lot more than test flying, with the inclusion of the development of many manufacturers and types without any specific mention of test flying. So the title of Test Pilots is somewhat misleading. Both military and civilian aircraft are covered.

The book is somewhat light on material prior to 1914. Not that unexpected as flying development was taking place mostly elsewhere, particularly in France and the US. More surprisingly is the almost total absence of material relating to World War I. From a small construction base, British companies such as Sopwith, Bristol, Handley Page, Avro and Vickers produced numerous types, with the Vickers Vimy bomber design being the first to fly the Atlantic. These companies, and their derivatives, were at the forefront of British aviation for many decades.

The end of the war was devastating for the British aircraft industry as a result of the cancellation of all military contracts. However developments still continued. Testing was subject to severe financial constraints, such as at de Havilland where only one parachute was available—for the pilot not the observer. The 1920s started to see the emergence of the market for passenger planes, although early versions were noisy, cramped, and with limited seating. Bad weather caused cancellations that nearly bankrupted Handley Page Transport—an average 30 minutes of flying per day and over a hundred forced landings. RAF Pageants stimulated public interest in flying and air racing. Harry Hawker was killed whilst testing a Nieuport Goshawk before a race.

Test flying started to become more scientific and methodical, at the same time as improved design and construction materials such as metal frames entered the picture. Aircraft started to become industrial rather than craft products. Wind tunnel testing began on scale models, although the frequency of instability reported in testing illustrated the gulf between tunnel tests and their interpretation by designers. Irrecoverable spins and structural failures were still commonplace. The Westland Dreadnaught stalled from 100 ft in its inaugural flight and was destroyed.

The 1920s and 1930s were perhaps the golden age in Britain of aircraft design and manufacture. As a result of increasing reliability—in engines at least, because increased military spending and growing public interest in air speed records caused the number of manufacturers and types to increase significantly, all generating more work for test pilots—but also more dangers too. One of the attractions of this book is that it documents numerous examples of designs that were failures, and explains why. However, progress came at the cost of injuries if not death.

By the middle of the 1930s, the monoplane had come into its own and engine development was (almost) keeping pace with aerodynamic design based on theoretical and wind tunnel research. And with the likelihood of another war increasing, a new era was approaching for test pilots with a new generation of military and civil aircraft.

By the middle of the 1930s, the monoplane had come into its own and engine development was (almost) keeping pace with aerodynamic design based on theoretical and wind tunnel research. And with the likelihood of another war increasing, a new era was approaching for test pilots with a new generation of military and civil aircraft.

Military aircraft testing brought time pressures and harsher testing. Terminal velocity testing required vertical dives, often with the loss of wings, tail, or both. Even with parachutes, escaping from such an incident was highly problematic. Also large-scale manufacture and deployment would uncover issues in operations such as airframe failures and engine fires. These could only be resolved through intensive and methodical retesting and subsequent redesign.

World War II resulted in the pinnacle of piston engine airframe design. It also led to the introduction of the jet engine and a new generation of aircraft. These aircraft arrived too late in the day to be of strategic value. Even the Me 262 which did get into operational use had too short an engine life (new alloy development) to be rolled out further, and in any event Germany was suffering from a catastrophic shortage of fuel for training and operational flying.

The test pilot job was moving from “a diagnostician to intelligent monitor.” Speeds were approaching the speed of sound. In 1945 a Gloster Meteor became the first aircraft to exceed 600 mph. Also in need of flight testing were associated items such as ejector seats. Although Chuck Yeager was the first pilot to exceed the speed of sound, John Derry was the first to do so in a plane that took off under its own power (the DH108 Swallow).

At the end of the war, Britain was at the forefront of aviation development. Unfortunately the country was also bankrupt. One area where it was felt British prestige could be upheld was tackling the air speed world record. Successful as this was for a time, financial payback was nebulous—the Concorde never recovered its development costs. And these endeavors came at a cruel price in testing, again a result of inadequate wind tunnel facilities.

Britain was still able to develop and test a successful range of aircraft. The English Electric Canberra/ Martin B57 was in service for over 50 years. The Harrier Jump Jet was instrumental in winning the 1982 Falklands war, but the country could not afford the development of a replacement.

With the benefit of hindsight, a country the size of Britain was never going to be able to remain at the forefront of aviation design across the board. Today it has shrunk to a few niche areas and making components for the European Airbus. Rolls-Royce has been able to remain one of the world’s foremost suppliers of aero engines, despite going bankrupt in 1971 during the development of the RB211 engine for the Lockheed Tri-Star [to which ED is forced to add that this was less the {British} maker’s fault than the {American} customer’s].

As mentioned at the beginning, this book covers a lot more than testing but is none the worse for that. It has some technical detail but also numerous entertaining anecdotes about the earlier days of flying.

Back in 1985, a reader could only wonder on reading this book what the 1919 Tarrant Tabor actually looked like; now, thanks to Google and Wikipedia we can see images of just about all the planes in this book. (The Tabor, a giant triplane with 4 engines crashed killing the pilots before leaving the ground.)

There exist numerous books on test pilots, but these overwhelmingly are (auto)biographies and/or about specific aircraft. Here instead we have a wide-ranging story of earlier British testing history. There was a US equivalent published about the same time, Test Pilots: The Frontiersman of Flight by Richard Hallion. Although both long out of print, they are available through the usual channels.

Author Don Middleton wrote another book on flight testing, Tests of Character, Epic Flights by Legendary Test Pilots (ISBN 1-85310-481-7). He was also a contributor to Aeroplane Monthly. He worked at de Havilland in WWII and witnessed the early flights of the Mosquito. In 1984 he was still able to interview a number of the contributors to this book.

Copyright 2026 Paul Lea (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter