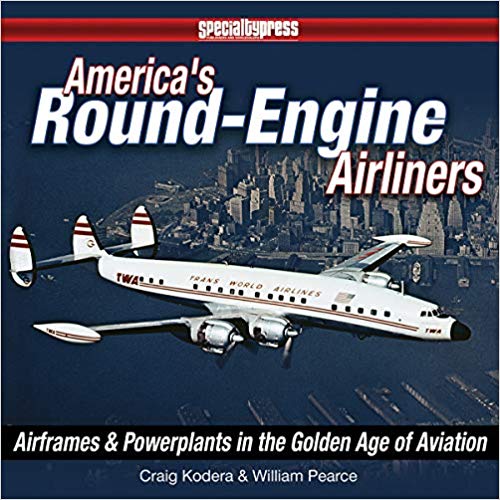

America’s Round-Engine Airliners

Airframes & Powerplants in the Golden Age of Aviation

by Craig Kodera and William Pearce

by Craig Kodera and William Pearce

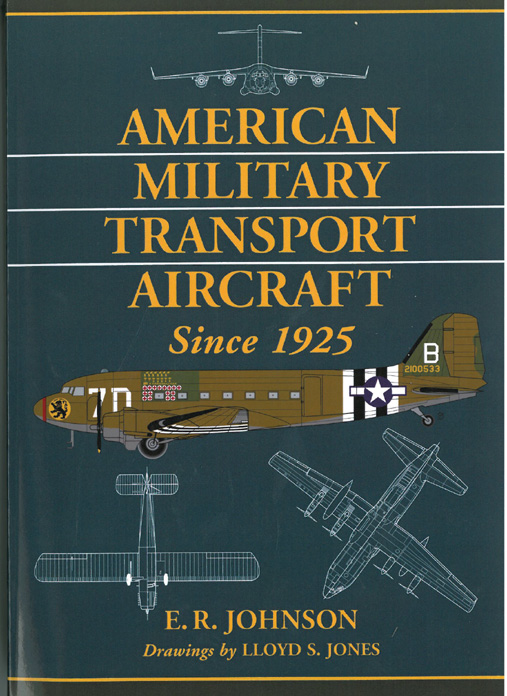

It all takes place in a modest span of time. Commencing in the 1920s with a single-engine airliner that seated six with a 9 cylinder engine capable of 200 hp at 2,000 rpm, to four engines each with 18 cylinders developing 3,700 hp at 2,900 rpm and nearly 200 passengers at the end of the ‘40s to, (gasp!) full-on jet-powered airliners before the 1960s had dawned.

Oh, but those planes and powerplants in between. That’s the story—equal parts romance and nostalgia and the more serious brain-engaging technical—that makes America’s Round-Engine Airliners such a can’t-put-it-down read for those of us fastened to terra in our reading chair.

The co-authors—each of whom, in his area of writing that are clearly delineated throughout the book—are the real deal. Craig Kodera flew commercially for Air California, then American Airlines after it purchased and absorbed Air California. Tech writer William Pearce can clearly explain mechanical design and operation but that’s not all, for he applies that knowledge to help make aircraft engines—particularly those round-motored air racers—run optimally.

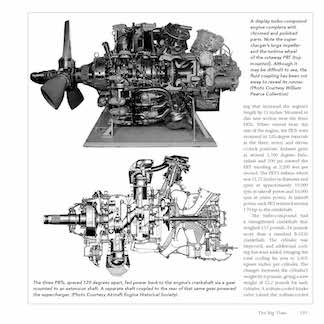

Chapters describe chronologically the growth of commercial aviation with Kodera opening each chapter describing airframes and cabin and cockpit amenities of the offerings from the various builders. Then Pearce takes over and delves into how the engineers overcame challenges and kept engines evolving. Those powerplants that ended up being commercially produced are shown in well-captioned cutaway diagrams and photographs as the text narrates about them further.

The book starts by tracing the hows and whys of inline engines especially noting the pros and cons of air or liquid cooling and why that led to the first round motors with but a single set (bank) of cylinders. As those engines became more sophisticated they had multiple banks of cylinders and, eventually, the gearing enabling the propeller blades’ pitch to be varied for best efficiencies, too.

Of particular interest are the charts about the motors that accompany and augment the text. Of each pair, one chart indicates by airframe manufacturer and its model which airliners used that engine and the other chart gives that same motor’s non-airliner major applications. As an example a pair of Wright’s R-1820 Cyclones propelled the preponderance of Douglas DC’s 1, 2 and 3 as well as Curtiss’ T-32s and two pair were on each wing of Boeing’s 307. Even more airframe manufacturers used the same engine including Grumman in, among others, its F4F Wildcat and S-2 Tracker; North American mounted it in its P-64 and used the most in its even more numerous T-28 Trojans despite those trainers being single engined. And because the book is about airliners, the latter “non-airliner applications” is bonus information not covered in the text.

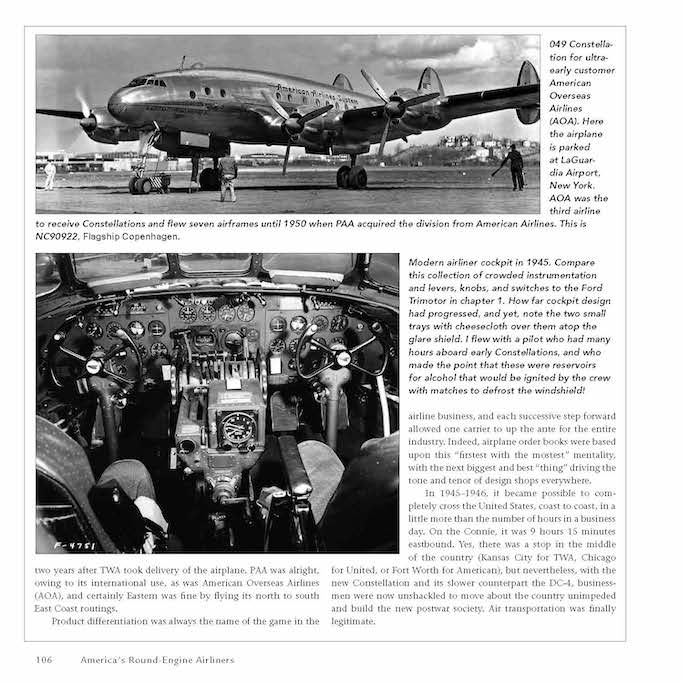

In the nostalgia category certainly are the gorgeous images of fondly remembered airplanes, many in their airline livery. With Kodera’s recounting about the amphibians of the 1930s including the magnificent PanAm Clipper one casual remark he makes in this segment invited your commentator to do a bit more searching.

In the nostalgia category certainly are the gorgeous images of fondly remembered airplanes, many in their airline livery. With Kodera’s recounting about the amphibians of the 1930s including the magnificent PanAm Clipper one casual remark he makes in this segment invited your commentator to do a bit more searching.

Depending upon your age and life’s experiences, you perhaps had first tasted a professionally made “real” Irish Coffee at San Francisco’s Buena Vista Café which touts itself as the 1952 originator of the drink. But there on page 85 of this book’s 216 are words indicating the origin might have been years earlier, in 1939 or ’40, in Foynes Island, Ireland where a PanAm transatlantic Boeing Model 314 Clipper landed. It was chilly and damp outside and attempting to ameliorate the passenger’s discomfort a creative employee offered them a libation of warming Irish Whisky mixed into coffee with a few grains of sugar and topped with the rich local and slightly whipped cream.

The next major aviation hurdle required infrastructure development on the ground, airports with runways to handle that next generation of airliners that first had two, then four engines. Of the latter perhaps the most remembered is Lockheed’s graceful and beautiful Constellation, more familiarly “Connie”. Constellations began plying the skies after World War II with flight motivation provided by Wright’s R-3350 18-cylinder iteration of its Cyclone.

The other big new postwar passenger plane was created when Boeing revised its military B-29 to civilian use and was kept aloft by Pratt & Whitney’s R-4360 28-cylinder Wasps. Lockheed replied by stretching Connie into the Super Constellation. Douglas and Convair and others weren’t idle but, as alluded to earlier, the engineering advances at both Wright and Pratt & Whitney was all important as the airlines themselves kept the pressure on for engines ever quicker, capable of carrying bigger (heavier) payloads, yet operating more efficiently.

One of the more compelling and interesting segments titled “Wright versus Pratt & Whitney” comes toward the end as William Pearce discusses the strengths and weaknesses of each from the engineering as well as the engines produced points of view. And there are some significant differences as he points out and supports giving the edge to Pratt & Whitney, summing it this way: “P&W’s employees built aircraft engines; Wright’s employees worked for a company that built aircraft engines.” Yet, in the end, their “products were on a par with each other” and today “no classic aircraft or warbird operator is removing Wright engines . . . and replacing them with P&W engines.”

It’s a splendid book whether you look at and read mainly the airliner nostalgia and history or the more technical engine and engineering aspects. Perhaps you’ll even do as this commentator and happily read it in its entirety and enjoy, reminisce, and learn with each turn of each page.

Copyright 2019, Helen V Hutchings (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter