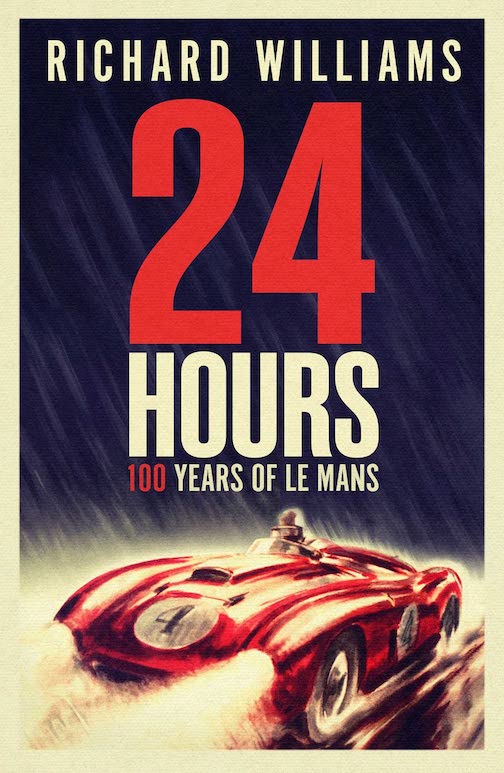

24 HOURS, 100 Years of Le Mans

by Richard Williams

by Richard Williams

“The combination of Helmut Bott’s chassis and Hans Mezger’s 4.5 litre flat-12 engine added up to nobody’s idea of the sort of fast tourer that the founders of the 24 Hours of Le Mans had in mind.”

—Richard Williams, on the Porsche 917

“Say something once, why say it again?” was the rhetorical question asked by David Byrne in Talking Heads’ Psycho Killer. I was thinking the same when I heard that Richard Williams’ new book was about Le Mans. Les 24 Heures du Mans, the endurance race so famous that even lay people have heard of it, is not exactly uncharted territory when it comes to being written about. But Williams has serious form when it comes to familiar subjects—his book on Stirling Moss (The Boy–A Life in Sixty Laps) was an endearingly quirky look at the man who had risked becoming a caricature of his former self. But, as I scanned the index to 24 Hours, I sighed as I realized that 21 out of the (oh yes) 24 chapters were year on year accounts of every race since 1906. This was going to be a long plod of a read—I rate Williams very highly but, even Homer nods, right?

Well, no, actually. Because this is a terrific book from which the reader will learn that Le Mans isn’t just a race, not even a very famous one like its Triple Crown contemporaries, the Indy 500 and the Monaco Grand Prix. The 24 Hours transcends its genre—it is an entire ecosystem which has never ceased to evolve, adapting to and surviving the myriad slings and arrows the last century has fired at its custodian, the Automobile Club de L’Ouest, ACO for short. And there’s a long list, including war, death, political turmoil, competition, regulation, recession, civil unrest and environmental angst. All the bad stuff that Le Mans endured didn’t kill it but (copyright F. Nietzsche) made it even stronger. As I write, Ferrari is on pole position for the 2023 race*, and up against serious competition from the big beasts of endurance racing, including Peugeot, Porsche, and Toyota. It’s been fifty years since Ferrari last ran here (with Arturo Merzario taking pole in the 312PB) and there could be no better place to stage the comeback drama than the 8-mile-long theater of Le Mans.

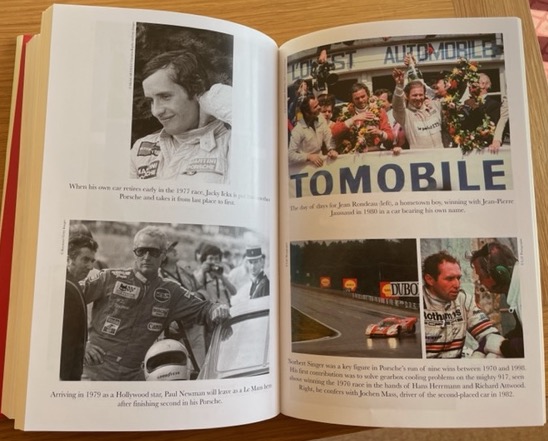

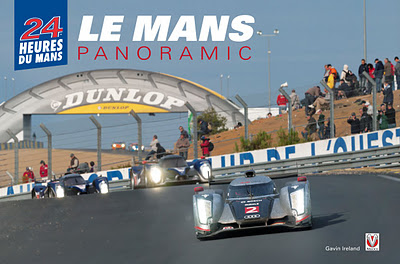

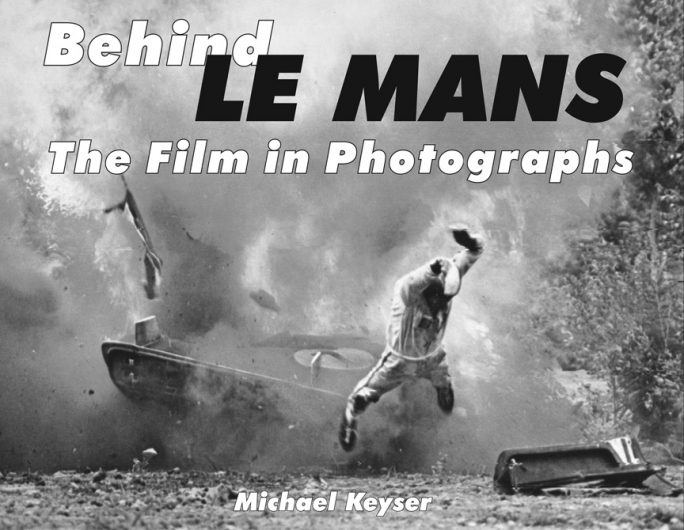

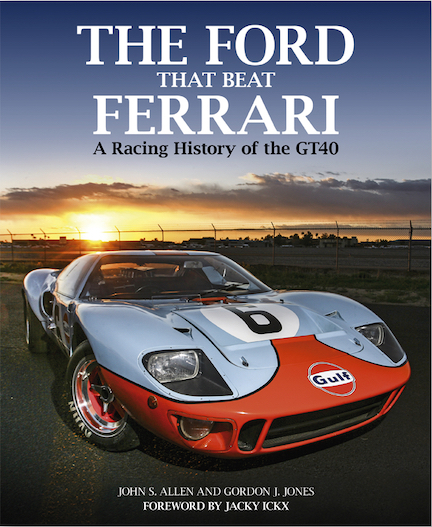

The 495-page book has been produced to Simon & Schuster’s usual standards. It is attractively laid out, the text is in easily legible font, and its cover price is reassuringly affordable. There are illustrations, but they feel like an afterthought and the legion of bigger and vastly more expensive books about Le Mans are much better in this respect. But they aren’t written by Williams, and it is his insight and human touch that elevate this book from potential back marker to the front of the grid. I expected—and received—the litany of winning machinery, such as the Bentley Speed Six and Ford GT 40, tales of heroic drivers like Ickx and Kristensen, of victories being snatched from the jaws of defeat (Rindt and Gregory [and maybe Hugus?]) in 1965) and vice versa (Toyota in 2016). But what makes this book compelling is the account of the forever-changing track itself, and the story of how the ACO has adapted and innovated to enable the race to become a centenarian. In parallel with that narrative, the author applies a compassionate and insightful account of the fate of people, few of them well known, whose names will forever be associated with Le Mans. Men like Roger Dorchy, who drove the WM-Peugeot P400 to 258 mph on the Mulsanne, thus realizing the dream of WM boss Gerard Welter.

Richard Williams is a man whose cultural hinterland encompasses much more than motorsport, and I enjoyed his off-piste excursions into how Le Mans was also a prism through which cultural shifts could be observed. This was the race that enjoyed its own theme songs, and Williams recounts how France’s “cultural compass had swung to the USA” in 1960, as Briggs Cunningham returned with a pair of Corvettes, soundtracked by “T’aimer follement,” sung by the 16- year-old Jean-Philippe Smet, better known as Johnny Hallyday.

Stalin’s apercu that “the death of one man is a tragedy, but the death of a million is a statistic” was echoing as I read Chapter Nine—entitled (with a nod to Hemingway) “Death in the Afternoon.” The opening words are these: “Eleven year old Pierre Rouchy left home on the morning of 11 June 1955 with his parents and his brother and sister, Jacques and Helene.” We know how this story ends—Pierre, the boy “of good humour and . . . gentle and friendly character,” was to become the youngest victim of motor racing’s darkest hour. The circumstances of Levegh’s crash in the Mercedes 300SLR are embedded in the mind of every motor racing enthusiast, but Williams’ account still shocks. It enrages too—Mercedes rightly withdrew after one of its cars killed 84 people, mainly spectators, but one of its surviving drivers, Stirling Moss, “couldn’t see what the withdrawal would achieve. It wouldn’t bring back the dead.” Some might say in his defense that such callous words were spoken from the foreign country of 1955, but for sheer crassness they were only surpassed by the man who was the indirect but real cause of the crash, the bow-tied Mike Hawthorn. It was his driving of the D-Type Jaguar that triggered the blameless Lance Macklin to swerve his Austin-Healey 100S into Levegh’s path. Was it any wonder the French press was outraged by Hawthorn and co-driver Bueb’s oxymoronic lap of honor “with a bottle of champagne wedged between them.”

The truth stranger than fiction is that, 44 years later, history almost repeated itself. In the author’s words, “The sight of a silver Mercedes flying through the air before crashing to earth evoked the unhappiest of memories.” The maelstrom of airflow flowing over, and under, 200 mph race cars can have violent consequences, as has been seen not only at Le Mans, but in Can-Am racing and elsewhere. Mark Webber’s Mercedes CLK became airborne not once but twice, first taking flight approaching Indianapolis on Thursday practice, and doing the same on the Mulsanne straight during the race warm-up. In his autobiography, Webber was withering in his criticism of the team, all the more so because, five hours into the race, teammate Peter Dumbreck’s CLK “was somersaulting, soaring almost to treetop height as it went through two complete back flips.” As Williams puts it, “The historical parallel hardly needed to be stressed.” Except, presumably, to team manager Norbert Haug . . .

There is much to savor in this book, because the real story of Les 24 Heures is about how the ACO curated their treasure, about the roles played by the bit-part cars and drivers and, most of all, about the sea of humanity that has been packing the circuit over one long weekend almost every summer since 1923. Readers will realize quickly that the ACO hierarchy has always been made up of the smartest of cookies, right back to the race’s conception in 1922 by “The Three Men in Paris”—Georges Durand, Emile Coquille, and Charles Faroux. They and their successors have been responsible for a circuit that is now on its eleventh iteration, and it will keep evolving as long as cars are raced, however long or short a time that might be, as Williams reflects in the last chapter, “Nightfall.”

Le Mans, just like the Indy 500 (if nothing else), transcends its status. Both races are sui generis, effectively laws unto themselves. Literally so, sometimes, and how wise was the ACO to shrug off the toxic embrace of Max Mosley and Bernie Ecclestone in 1989. The Piranha Club duo who had already fashioned Formula One in their own image and then tried to do the same with sports car racing. Their absurd and disgraceful plot was to emasculate the legendary endurance races, including Le Mans, by reducing them to 220-mile sprints. I assume that Mosley and Ecclestone, enslaved to TV ratings, realized that a fickle TV audience couldn’t be guaranteed to concentrate for more than two hours. I liked the author’s crisp account of how the ACO “decided not to swim into the mouth of the predator . . . (but) to continue to run the race as they saw fit.”

Le Mans has long offered rich pickings for big screen drama. Thanks to his 1971 film, Le Mans, Steve McQueen has benefitted from post-mortem beatification, and Gulf-branded kit is de rigueur for middle-aged men who bathe in the King of Cool’s reflected glory. Ford v Ferrari (aka Le Mans ‘66) created a fanbase that the spiky Ken Miles never enjoyed in his lifetime, if amongst a demographic who had never heard of the British driver before 2019. And in 2023, YouTube can offer extraordinary footage of Le Mans, often in-car, and in real time. But as Richard Williams reminds us, this race has been and always will be about much more than the headline-grabbing Bentley Boys, the achingly lovely Ferrari P4, or the starkly efficient Audi R18 and Porsche 919. Starting numbers have varied from a nadir of 17 in 1930 to 2022’s 62, but it is the also-rans, the vanity projects, and the vainglorious that add texture and color to the saga. It is to the book’s credit that it doesn’t neglect the lesser members of the dramatis personae like Automobiles DB, or the car that brought “money, glamour and noise” (the Panoz) and the “eye popping front-engined, front-drive GT-R Nismo” in 2015.

This is not the only book you should own about Le Mans—no collection is complete without Rainer Schlegelmilch’s photographs—but Richard Williams’ perspective, sometimes oblique, rarely conventional but always insightful, has done justice to an event that is more of a phenomenon than a race.

- And a Ferrari won. Forza!

Copyright John Aston, 2023 (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter